(via)

Nefarious may seem a strong word to apply to cake-scented perfume, but bear with me for a minute, okay? Years ago, I was copy editing at a women’s magazine, and one of the beauty pages was all about food-scented products—lemon cookie body souffles, cotton candy lip gloss, caramel body polish. Something about it just nagged at me, but I couldn’t put my finger on why. The promotion of these products felt somewhere between belittling, infantalizing, and placating—even as I admitted they smelled nice—and though I’d never really thought much about the products on an individual, something about seeing all of them grouped together on the page vaguely unsettled me.

I tried articulating this to a friend, who then got worked up because she was a fan of (the pretty awesome) Lush, which liberally uses food scents in its collection, and before I knew it I was on the other end of the feminist beauty argument than where I’d prefer to be: I was saying there was something politically off-putting about a grown woman smelling like cake, and she was saying that the right to revel shame-free in sensual pleasure was something feminists had fought for, and I think we settled it by meeting midway at peppermint foot scrub, but I don’t really remember.

It stuck with me, though, in part because one of the arguments I’d used fell flat when I gave it more thought: I’d argued that foodie products were pushed as an alternative to actually eating food. And you do see some of that, to be sure, tired blurbs about how slathering on a cupcake body lotion will “satisfy—without the calories!” But it usually seems like such a desperate bid for beauty copy that I have a hard time believing anybody actually uses sweet-smelling body products in an effort to reduce sugar intake. (Besides, logic would dictate that it would do the opposite, right? If I smell cookies, my instinct hardly to sigh, “Ah! Now I don’t have to actually eat cookies!” but rather to optimize cookie-eating opportunities.)

But it wasn’t until I read One-Dimensional Woman by Nina Powers that I realized what it really is about foodie beauty that gets to me. Powers on chocolate:

Chocolate represents that acceptable everyday extravagance that all-too-neatly encapsulates just the right kind of perky passivity that feminized capitalism just loves to reward with a bubble bath and some crumbly cocoa solids. It sticks in the mouth a bit. … I think there’s a very real sense in which women are supposed to say ‘chocolate’ whenever someone asks them what they want. It irresistibly symbolizes any or all of the following: ontological girlishness, a naughty virginity that gets its kicks only from a widely-available mucky cloying substitute, a kind of pecuniary decadence.

Which, coming from a voice as right-on as Nina Powers, makes me want to host some sort of sit-in at Cadbury HQ*, but let’s face it, I’m not an organizer. So take that sentiment and add it to not even actual chocolate but things that just smell like chocolate (or cupcakes, or buttercream, or caramel, or any other boardwalk treat) and that are meant to make you feel and look soft and pretty—harmless, that is—and yeah, these products carry more than a hint of unease. Foodie beauty products are designed serve as a panacea for women today: Yes’m, in the world we’ve created you have fewer management opportunities, the state can hold court in your uterus, there’s no law granting paid maternal leave in the most powerful nation on the planet, and you’re eight times more likely to be killed by your spouse than you would be if you were a man, but don’t worry, ladies, there’s chocolate body wash!

I’ve no doubt that the minds creating these products are doing so because they seem like they’ll sell, and less importantly, they seem like fun. Hell, they are fun: Sweets are celebratory, and why shouldn’t we remind ourselves of celebration, especially with something as sensual as scent? But the motive needn’t be intentional to be nefarious. Men like food too—remember that study about how the scent of pumpkin pie made them horny?—but it’s not like companies hawk products to men that smell like food that’s been successfully gendered via marketing.** (I mean, certainly there are men out there who dab barbeque sauce behind their ears and fill their sock drawers with sachets of crushed pork rinds, but marketers haven’t caught on. Yet.) Food-product marketing is specific to women (mint, ginger, and citrus scents aside), for we’re the ones still connected with the domestic sphere and all the “simple pleasures” it brings. Men get forests, the oceans, the dirt of the earth itself. We get flowers and a birthday cake.

Now, at this point, Dear Reader, I have a confession to make. Actually, I have at least seven confessions to make, starting with: As a teenager, I used vanilla extract as perfume. Which is not to say I haven’t also purchased a bevy of vanilla perfumes over the years—for I have—in addition to gingerbread body scrub, brown sugar lotion, a chocolate body oil that inexplicably made me sleepy, an angel-food-scented bar of glycerin soap with a plastic cutout of a slice of birthday cake floating in the middle, and a “Fortune Kookie” body gel that I finally discarded, at age 33, not because of the scent but because of the accompanying shimmer. So I’m not immune to the charm of smelling like Betty Crocker. I wore these products most frequently as a teenager but carried some to adulthood and why not? They do smell good, after all; that’s the whole point. And they trigger something that on its face seems harmless: Part of their appeal lies in how they transport us back to an age when all we needed to be soothed was a cupcake.

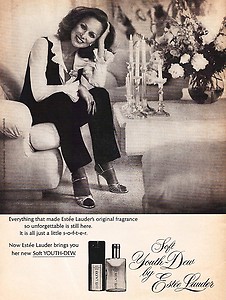

At the same time, they don’t actually transport us to being that age; they transport us to a simulacrum of it. When I was 6, if I wanted to smell like anything it was the Estee Lauder perfume samples my mother got free with purchase. Smelling like fake food was for the only thing more powerless than a 6-year-old girl—Strawberry Shortcake dolls. I loved the scent of those dolls but never wanted to smell like them myself; it wouldn’t have occurred to me. It was only when I was a teenager and began to actually walk the line between girlhood and womanhood that I suddenly became obsessed with smelling like a Mrs. Field’s outlet—and sure enough, there’s that “naughty virginity” Powers mentions. I wholly bought into what she outlined: Smelling like cotton candy let me put forth the idea that I was the kind of girl who would enthusiastically dig into a vat of the stuff, i.e. the kind of girl who liked to have a good time, but not that kind of good time, except of course it was that kind of a good time, because the biggest thing that had changed from the 14-year-old me dragging torn-out magazine samples of Red Door across her wrists and the 15-year-old me dabbing vanilla onto my neck was intimate knowledge of what an orgasm was. I liked feeling a little hedonistic, in the most good-girl way possible. Smelling sweet at 15 was lightly naughty without being seamy in the least—if anything, its naughtiness was so covert that I didn’t realize that scenting myself as a Sweet Young Thing had any implications other than, well, sweetness, even though my near-panic whenever I came close to running out of my Body Shop oil should have alerted me that I had more invested in this whole vanilla thing than I could articulate at the time.

Which is not to say that every teenager—or every adult woman—who spritzes on a little angel food perfume is a wanton Lolita, or that even if they are, that we should raise our eyebrows about it. Certainly I was better off expressing my “wantonness” (can you be wanton if you went off to college a virgin?) through vanilla perfume than I would have been by expressing it with anyone resembling Humbert Humbert. And as much as this blog might imply I believe otherwise, sometimes a candy cigar is just a candy cigar. The perfume I wear most frequently now*** is indeed a hint sweet—carnation, rose, bergamot, milk, and honey—and while I’m not so arrogant as to think the 15-year-old me had complex sociological-developmental motivations for wearing vanilla perfume but of course the 35-year-old me just likes what she likes, the fact is, I do wear it because I like it. I don’t want to imply that any of us should stop using lemon cookie body souffle or toss out our Lip Smackers—joy can be hard enough to come by plenty of days, and if it comes in a yummy-smelling jar, well, that’s reliable enough for me not to turn my nose up at, eh? I just wonder how harmless something can actually be when its existence is predicated upon announcing just how harmless it really is.

*On chocolate, briefly: I do like the stuff, though have never lived for it; I’d rather have lemon, caramel, or coffee-flavored confections most of the time, and I really only like chocolate-chocolate, not chocolate cake or chocolate ice cream or whatever. That hasn’t stopped people around me from assuming I have a great love of chocolate and furnishing it to me as a treat, to the point where I myself forgot that it’s not my favorite sweet and found myself falling into some sort of cocoa zone where a chocolate bar became a reward for a job well done, or for 24 hours fully revolved, whichever came first. It was only upon realizing that the fellow I was dating looked forward to our shared chocolate bars more than I did that I realized I’d talked myself into becoming a chocoholic, and I haven’t looked back since. I maybe buy one Lindt bar every other month?

**There is, of course, the curious case of Axe Dark Temptation, a cocoa-scented body product line for men whose commercials featured women gnawing at men enrobed in chocolate, elevating depravity to an entirely new level.

***Black Phoenix Alchemy Lab's Alice, since you asked.