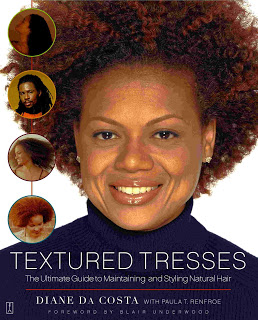

Diane DaCosta—celebrity hair stylist, textured hair guru, product developer, and author—was styling her clients naturally years before naturally textured hair became as popular as it is now. Her book, Textured Tresses: The Ultimate Guide to Maintaining and Styling Natural Hair, educates African American women and other women with textured hair on how to maintain and care for their hair, and shows that glamour need not be synonymous with relaxed hair. Instead, she works with clients' texture to achieve a variety of looks, preserving the health of their hair and paving the way for a natural hair explosion along the way. Her latest project, Beauty Girl Talk for Teens, aims to educate young women on self-esteem, self-awareness, and proper hair care that will ensure they have hair for years to come (traction alopecia is one of the fallouts of relying exclusively on weaves). We talked about the evolution of African American hair, the role of spirituality in hair care, and why weaves aren't necessarily to be avoided—even in primarily natural care. In her own words:

On the Legacy of African American Hair

African American hair has been an evolution in America. We go through these cycles: In the '50s, we had natural hair, but we would press it and create Marcel waves. In the '60s and '70s it was the big Afros and cornrows; in the '80s we put relaxers in. We were graduating from college, getting jobs in corporate America—as African Americans and as women. In the '80s we were assimilating, and by the '90s we had arrived in corporate America. So now we want our identity back, but how can we do it?

As far as hair is concerned, first it was with braids, but very conservative braids. As time went on, after a couple of years we started bringing back our own natural hair in different styles. It's just sort of the evolution of a people identifying themselves and wanting to wear their own hair—and a little rebellion.

We're more accepted and equal in the workforce now, and the look has to reflect progress all across the board. All things start at the ground, so while you might not see a look in corporate America right away, you'll see it in the streets of Harlem. And in middle America they're still going through their revelation: twisting, coiling, braiding, locking. But here in New York, we're over it! We're the fashion capital of the world, and we've already moved onto the next level.

Now the big thing is that you can wear your own hair naturally curly and wavy with some product or texturized. Entertainers wore their hair big and curly since forever, but they wore weaves. Now you can actually get your own hair to look like the entertainers', but you can also wear weaves. Weaves are accepted all over now—and girls are wearing weaves that are curly instead of just straight and long.

On the Conflict of "Natural"

Twenty years ago I would have had a different perception, but now I think African American women are loving and accepting their hair more and more. They're accepting it in its natural state and letting it grow out healthier, and then doing whatever they want to do to it. But there's still an emotional association with self-worth. Now you have women who are fine with their natural texture—we've established that the natural hair movement is here to stay, and we've accepted the array of styles you can do with natural, textured hair—but it's the length that messes with women's minds.

Why not just accept, "Okay, my hair is natural, or relaxed, or whatever—but I want long hair, so I can put a hair piece in it"? There's this conflict: I want to be natural, and I want long hair, but I don't want an extension.

It can be a personal, emotional conflict within you. Not all weaves are bangs or side swept—there are weaves and extensions that mimic natural hairstyles, like braided extensions or textured weaves. There doesn't seem to be as much internal conflict among women about that—maybe because it's a quote-unquote "natural" style, an African style. I mean, it's still not completely your real hair. But it's a conflict that runs deep.

On Healthy Hair (and Fabulous Wigs)

If you're doing weaves over and over again because you don't have the texture you want, you might end up destroying your hair and your follicles. That has always been a challenge with African American women who don't accept their own texture. There's this mind-set of: I want that kind of hair, so I'll have it—I'm going to weave it, I'm going to do this, I'm going to do that. And yes, you can do all of those things, but you have to make sure that it's healthy for your hair and scalp first.

Once you accept and love whatever you have, you can get whatever look you want. Clients come to me after they've been doing weaves for years and years, and by that point I'm seeing something ridiculous. A lot of balding. Like, "Your stylist didn't tell you that you have traction alopecia? Your hair is falling out!" But sometimes stylists figure, the client is wearing a weave—who's going to see it? But eventually you'll have no hair and the client will start thinning and perhaps balding.

Wigs were never meant to cover up baldness. Wigs were always for accentuating. From way back in the '50s and '60s, my grandmother wore wigs. Not because she didn't have hair, but because she wanted to be more fabulous. Now people are wearing wigs because there are so many great wigs. But some who abuse weaving might end up needing them.

On Transformation

I was raised Catholic, which never resonated with me. And when I do something, I do it full force. So when I tried to find my own spirit, I had a spiritual transformation, and I went for it all. I started meditating. I became a vegetarian. I cut off all my hair, and wanted to start locking it. Natural hair wasn't a bad thing for me—my parents are Jamaican, and growing up I had an example of what natural hair would look like in my family. So I knew it wasn't something to be ashamed of—but still, in my family, straight and long was preferred. When I had my transformation and cut off my hair, my parents thought that wasn't right. My family said, “She's going crazy!” But I was really coming into my own creative being. I went through it and found myself, and came out of it a great thing.

After that, everything for me had to be as holistic as it could be. After learning about my diet and what I had to eat and just being all natural, I never put a relaxer in my hair again.

I didn't even lock at first; I wore my hair in a natural short cut. Then when I got into the hair industry and started going to hair shows, I wanted to try different things—at that time the Halle Berry haircut was out, so I restyled my hair. And that was cute for a while, but it wasn't really going with my philosophy. I was still a cosmetologist: I believed in using relaxers for those who want it, but from then on I never relaxed the hair bone-straight, which was what everyone else was doing. I developed my own technique of texturizing and softening the hair. There is still always a wave pattern in the hair once the hair is softened.

If you want your hair 100% straight with a relaxer system, then you go to somebody else. You don't come to me. This is where client education comes in: After the relaxer or texturizing application—the additional heat actually makes the hair straight. So if you over-process the hair or relax your hair at 100% straight, and then you roller-set it or blow-dry it, now it's at 110%, 125%. Now you're over the limit; you're breaking your hair. I tell my clients, "So you want me to damage your hair, right? But guess what—I'm not doing it."

And my clients really listen to me because I educate them about their hair. I believe God blessed me from the beginning, because once I went to Turning Heads [a leading natural Harlem salon], I was featured in the magazines and styling celebrities. It was my destiny that when people came to me they listened to what I was saying. God put me in a position to be an influencer through media, and that's what people listen to.

On Mainstream Companies

The hair product industry is booming, especially for natural hair—it's a valuable means of revenue, especially in a recession. Once you learn how to style with products, you can do it yourself. Every mainstream company has a curly product line or some kind of natural hair care line.

I've been doing this for 22 years, and I see that texturizing natural hair is huge now and finally recognized as an alternative to relaxing the hair straight.

I was just looking through one of my general market trade magazines, and I saw this DVD set actually named "Artificial Texture"—all these white girls with blonde hair are in it with curly and wavy hair textures, and the DVD is teaching stylists how to create curls and waves. So now it's called "artificial texture"! I think it's a great thing that they're teaching texture to stylists who don't have textured hair and don’t know how to work with textured hair.

A lot of women of color don't know they can use certain product lines on their hair texture. If there's a multicultural line, sometimes they don't say it’s for use by African Americans or women of color; they call it something else. For example, I worked on a product line that was specifically designed for people of color with textured hair. I tested and helped develop the product line for curly hair, but they only have a Spanish girl on their packaging, not any brown girl at all.

Phyto, on the other hand, has a line for people of color, and they use people of color in their advertising.

They don't say it's for people of color, though—they say it's for frizzy, curly, and relaxed hair. Which is the better way to do it, when the product is specifically for women who have textured hair?