People sometimes make the mistake of thinking that because I’m into beauty, I must also be into fashion. I enjoy clothes that I find attractive, but fashion? Frankly, it bores me. My preference for the beauty world is partly practical (the price point is lower) and partly narcissistic (I can’t really see myself in clothes since I don’t have a full-length mirror, but I see my face a zillion times a day, so I’d rather just adorn that).

But sometimes I think the real reason I’ve always been drawn to makeup is its subversive possibilities. There’s obvious subversion—goth-girl eyeliner and the like—but that’s not what I mean. What I mean is that makeup looks like it’s the stuff of soft, feminine compliancy, but if you want it to be, it can be steel. Someone might look at you with good-girl makeup on—all tasteful lip liner and dainty blush—and make the mistake of taking you at face value. But you know that those tubes and creams channel your game face before you walk out the door every day. They don’t give it to you; that’s yours already. But if you imbue your lipstick with the possibility of swagger, that is exactly what it will bring out. Let them think you just care about making your lips look like ripe berries. You know the bud that comes before the fruit.

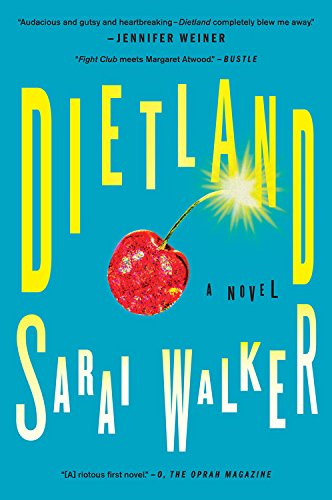

I’m not sure whether any of the characters in Sarai Walker’s novel Dietland would agree with me on this front. You might have heard of the book (the paperback version comes out Tuesday), which received appropriately rave reviews from select corners of the internet, with the juicy cover blurb for the upcoming paperback reading “Fight Club meets Margaret Atwood.” (I dare you to not read it now, with that kind of endorsement.) But the idea that beauty is subversion is actually what sets Dietland's action in motion. The book got a lot of attention for its crushing of what you might call “fuckability mores.” The main character, Plum—a young, fat employee of a teen magazine looking forward to her upcoming weight-loss surgery—becomes entangled with an underground feminist collective that at one point throws her into a crash course on “fuckability,” leaving her waxed, wobbling in high heels, and questioning whether the supposed rewards of weight-loss surgery are worth it. Combine this storyline with the book’s news bursts about a vigilante organization that targets people who have committed acts of violence against women—an organization that may or may not have ties to the collective Plum is involved with—and the book’s message seems clear. The things women do to make ourselves look fuckable are acts of violence against women, oppression at its most masterful.

Beauty goes deeper in Dietland, though. Walker treats beauty satirically throughout, to the point of ludicrousness—at one point, an editor is caught masturbating with a lipstick tube, and another woman is nearly crushed to death by eyebrow pencils. Which makes sense, as beauty culture itself can be nearly as ludicrous: We put hot wax on our genitals, snail slime on our faces, and chemicals on our skin to make it look tan. But it’s really the ways the heroine gets drawn into the book’s events that shows the deeper potential for beauty. Through her job at a teen magazine, Plum meets Julia Cole, the manager of the beauty closet, a massive hangar-like space filled with cosmetics that the media conglomerate’s female employees can use before media appearances. Julia looks the part of a pert, shiny beauty manager, but it’s a disguise—she is literally unrecognizable without her shapewear and makeup—that she wears to commit feminist espionage. Julia’s position as beauty closet manager works nicely on the level of sheer storytelling, both logistically and thematically, as beauty is a pretty straightforward package in which to deliver a feminist critique. Women are frequently told that beauty is where the answers are, and in Plum’s case that’s literally true: That’s where she’s first clued into what becomes the main action of the book.

Throughout much of Dietland, as in much of feminist discourse, beauty in its traditional forms—including both the starved, plucked beauty that conventional femininity invites, as well as the beauty industry at large—is, if not the enemy, the enemy’s avatar. But it’s not just irony that sees the beauty closet as the place where Plum begins her awakening: It’s subversion. We’re told that beauty is a way to power, which might be true in a certain limited fashion. But it’s also a route to discovery. Investigating her own body is how many a woman arrives at feminism, and once she’s there, she still might find that beauty is a useful in-road to connecting with other women. Beauty is also how plenty of women have embedded themselves into the worlds of people who just might listen to the cause. Remember, Gloria Steinem was always more radical than Betty Freidan, but because of Steinem’s sensational looks, her feminism was seen as more palatable in the 1960s than Freidan’s. It wasn’t fair, and yes, of course that’s part of what feminism is trying to fix. But that doesn’t mean that in the meantime we should ignore that subversion and write off beauty.

Not that the author herself necessarily agrees with me on this point: “Generally speaking, I don’t find beauty culture to be very subversive,” Walker tells me. “I think sometimes we might like to frame it that way to justify our participation in it as feminists. In my own life, I acknowledge that the use of makeup is a gendered practice, rooted in sexism, but that I wear makeup sometimes because like every other woman, I live in a sexist, looks-based culture that judges me based on my personal appearance.” But even within this acknowledgment that beauty is difficult to subvert, Walker sees possibilities: “There are women in fat activism who are focused on beauty and fashion culture, and I do see some subversive potential there. Fat women are encouraged to be invisible, to wear dark colors and blend into the scenery—until, of course, that magical day when we’ve achieved thinness. So I do see some subversive potential with fat women wearing bright colors, both in makeup and clothing, and asserting a very feminine identity that has traditionally been denied us. This can make fat-haters incredibly angry, like, ‘Who does she think she is?’ If it makes fat haters angry, it’s a good thing! I explore this in Dietland. Part of Plum’s transformation involves her feeling entitled to wear brightly colored feminine clothes, and she sees this as a way to give the finger to fat haters, and as a way to take up space in an unapologetic way. I think there are limits to what this can achieve as activism, but it can be powerful in some ways.”

Walker brings up another key point to what I see as the subversive possibilities of beauty: “I wanted to consider these products as part of women’s material culture—whether one likes it or not—and how this is a culture that for the most part excludes men,” Walker told me. “Men don't normally like being excluded from things, but as a group they seem to be fine with it in this case, and I think it's because makeup carries the ‘taint’ of femininity that most men don't want to be associated with.” I’ve always argued that beauty creates spaces for women to connect—sometimes literal spaces, as in the intimacy of hair salons, and sometimes figurative spaces, in that beauty talk can make for an easy conversational entrée. But this idea of beauty’s taint brings up a richer idea: that women are creating a culture for themselves that just might have jack shit to do with appealing to the male gaze. It’s tricky ground, of course; the vast majority of beauty work does appeal to the male gaze. But anytime women create a cultural space for themselves, and only for themselves (as well as genderqueer folks, and men who are willing to embrace that feminine stigma), a germ of subversion—perhaps of rebellion—is planted.

“All makeup is drag,” says Julia the first time she meets Plum. And at first glance, that might be the main takeaway of beauty presented here. But after her transformation, we also see Plum ask a makeup sales clerk to rim her eyes again, and again, with the deepest black eyeliner the store has. “My goal isn’t to look fuckable,” she says. “The look I want is Don’t fuck with me.”

It’s tempting here to be like, “See, Plum CHOOSES it so it’s different!” But I’m always hesitant to fall back on the language of choice as a feminist go-ahead for makeup, or high heels, or shapewear. It borrows the lexicon of reproductive rights, and while women’s bodies are at the center of both beauty work and reproduction, equating them feels pat. A woman should be able to terminate a pregnancy without justification, and I don’t want women to feel the need to justify their beauty work. But beauty work is not as black-and-white as abortion either, and there is room for considering reasons here. All makeup is not drag: When you want your makeup to say Don't fuck with me, you’re stepping out of high drag and stepping into motion. That’s easier to see when you’re wearing makeup in a way that is stylistically subversive. But that woman in the pearly pink gloss of steel? Her armor is not to be fucked with either.