Estee Lauder has been getting some nice press lately: Between a NYTimes business profile treatment and slideshow and the launch of Aerin Lauder's luxury lifestyle line, the cosmetics empire is aglow (reflected in its strong stock pricing). Quieter is the news about its layoffs after a $250,000 raise for one of its top executives. Business as usual, but in looking at Estee Lauder we see a reflection of America's contemporary beauty history: a push-pull relationship between the joys of treating yourself with care, and the world of hard commerce.

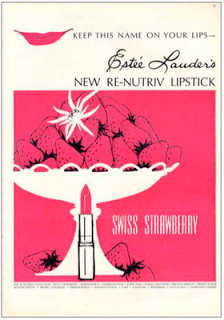

Estee herself successfully married capitalism and the essence of beauty: She knew that part of the fun of beauty was trying on a new look, pioneering the idea of the gift-with-purchase by giving away lipstick with every sale. She also understood that beauty was a lingua franca among women, hence her "telephone, telegraph, tell a woman" marketing technique, which placed a premium on word-of-mouth over conventional advertising. And she made it a personal rule to touch every single customer who came into her stores, and encouraged her staff to do the same—this might sound creepy or manipulative from a distance, but the literal laying-on of hands is one of the beauty industry's biggest gifts to us. As makeup artist Eden DiBianco pointed out in our interview, "It's the only non-medical profession where you're licensed to touch the public."

"Sex, Lies, and Advertising," Gloria Steinem's must-read essay on advertising in women's magazines, presents another side of a major company player. In it, she recounts meeting Leonard Lauder (Estee's son and then-CEO), hardly the thinking woman's corporate leader, whom she was courting in order to get Estee Lauder ad dollars in Ms.

"Over a fancy lunch that costs more than we can pay for some articles, I explain how much we need his leadership... But, he says, Ms. readers are not our women. They're not interested in things like...blush. If they were, Ms. would be writing articles about them. ... He concedes that beauty features are often cococted more for advertisers than for readers. But Ms. isn't appropriate for his ads anyway. Why? Because Estee Lauder is selling 'a kept-woman mentality.' ... He knows his customers, and they would like to be kept women. That's why he will never advertise in Ms."

She goes on to note that Lauder insists to this day that the conversation never took place.

Why should we care about a conversation that took place 20 years ago with a man who isn't CEO anymore? Because it's illustrative of the disconnect between the people buying the products and the people making decisions like how they're marketed, what they cost us, what techniques they use to hook us, and where they can cut corners. Beauty is a business, and they don't have a responsibility to fix whatever issues individual women have with our appearance. But I'd like to think that the decisionmakers at least don't have disdain for us and think that we enjoy being "kept women" simply because we like a quality moisturizer. So much of the beauty industry is built upon the illusion of it being at least cursorily pro-woman that it's a peculiar disappointment once we see the contempt a CEO has for his customers. Were it not for the woman-friendly potential offered earlier by this particular company, the fall wouldn't seem as crushing.

Seeing the business tactics being used by the Estee Lauder behemoth makes me sort of sad for Josephine Ester "Estee" Mentzer, who tinkered with her chemist uncle's face cream formula to come up with her unique formula. Where are the female CEOs of cosmetics companies? Sephora, L'Oréal, Unilever, Proctor & Gamble, Johnson & Johnson—all men at the top. Women hold creative and "soft" business positions (communications, human resources), but Andrea Jung at Avon is the only big lady kahuna at a major company. I don't think that women make better (or worse) CEOs, but it seems peculiar that a bunch of people who have never used the products in question are the ones major major decisions. Major decisions like saying their customers prefer to be "kept women." As beauty editor Ali pointed out, "Some of the big companies treat lipstick the same as diapers; they move their CEOs around and it’s always some dude who has the MBA calling the shots and treating all the products the same." Women are involved in product development and marketing, of course, but at the end of the day they answer to someone who fundamentally sees the product as a line item, not a face powder.

I'm thrilled that green beauty is getting more attention. But since we're making a push for earth-friendly ingredients, I'd like to see us all be just a little more aware of who's up top—and who's at the bottom. For the latter: Good Guide is a fantastic resource that measures the social impact and responsibility of hundreds of cosmetics, separate from their environmental and health measures (thanks to the Beer Activist for the tipoff about the hefty cosmetics portion of the site). Paying attention to this directly affects women: It measures responsibility in corporate governance (how do they settle, say, fair pay disputes?), measures of consumer safety (that's you, milady), philanthropy (are your dollars eventually going to go toward helping other women?), and workplace conditions (pink-collar workers in many cases).

As for who's up top? Besides Avon, in the big leagues, I'm at a loss.