I never dreamed I'd have an athletic body. I was a gym-class-fearing child, to the point where I would purposefully fall down stairs in the days leading up to the dreaded gymnastics unit; breaking an ankle seemed better than having to attempt to do a cartwheel in front of my classmates. I saw nothing wrong with sitting down on the playing field during T-ball games (to this day my parents swear I asked to join the team, and I can only assume that I was being ironic at an extraordinarily tender age); my favorite day of tennis lessons was our end-of-summer party because I got to stay on the sidelines and eat the racket-shaped cookies my mother had made for the occasion. Running The Mile—which I saw in my head like this:

—felt like torture, and I had to do it every year from grades 6-9, and I played sick every year until I realized I’d just have to do it on a day when the rest of the class was playing touch football or something and therefore able to watch me run The Mile, which was even worse.

I thought that way all my life—a singular aqua aerobics class my final semester of college notwithstanding, in order to "round out my course load"—until 2002. I'd broken up with a boyfriend, and it was one of those breakups that makes you wonder if you will ever be okay again, where being alone feels excruciating because you’ve cried all you can and you don’t know what else to do. Being on the subway felt okay for some reason, and since I wasn’t so despondent as to just ride the rails all day with no purpose, I took the opportunity to travel to gyms in the farthest reaches of all five boroughs to take advantage of their guest passes. (Plus, then I’d get really fit and toned and lithe and show him!)

The first time I entered a gym, it was in the Bronx, which I’d specifically chosen because I didn't know anyone who lived in the Bronx, so nobody I knew could possibly witness my fumbling around with the machines. I sat down at every machine in the place and read the directions so that the next time I went to a gym that would presumably not be in the Bronx, I wouldn’t look like a total fool. I stayed there for four hours.

Guest pass after guest pass, I worked my way through the city, and after a couple of months I realized that it was helping in ways beyond dealing with the breakup. My mood was improved, for one. My body, which hadn’t felt particularly out of shape before, began to feel...better. Like things were just working right. I was gaining confidence by knowing how to use the machines and free weights, and to my surprise I was finding that I was quickly able to up how much weight I was lifting—and, in fact, that I was lifting more weight than most of the other women on the floor.

And then there were the muscles. I had enough fat on me that it wasn’t visible for a while, but I could feel my arms getting more and more solid every week. Shaving my legs suddenly invited hazard because there was now a sharp little tennis ball where a soft calf had previously been. I distinctly remember looking at myself in the mirror while washing my hands and freaking out because there were these things moving in my chest, these ripply creepy-crawly things underneath my skin—and realizing that was my upper pectoral muscles, which I’d never actually seen before. I mean, I was no Colette Nelson, and you probably wouldn’t even have looked at me and called me “buff.” But I was distinctly more muscular than I’d ever been, and I’d even say I looked more muscular than the average woman of my age.

It turns out that my body actually is rather athletic. I still can’t catch, throw, or hit a flying object (gym-class phobia sets in even if a coworker tosses me a pen), and I would hesitate to say that I’m even in particularly good shape. But I’m reasonably fit; I can run a few miles without stopping; I lift weights. I even did some somersaults a few years ago when I went through a krav maga phase. Compared to the kid hurling herself down the stairs in 1983, I’m Mary Lou Fucking Retton. And when this fact hits me—when I am energized instead of exhausted after a run, or when a fellow gymgoer asks me to spot him, or when my doctor tells me that my heart rate is in the zone of conditioned athletes—I feel the type of gratitude and relief you can only feel when you realize that something negative about yourself that you’d accepted as truth is, in fact, not.

So the first time I saw “athletic body” in the “dress your figure” pages of a women’s magazine, I got excited. Finally, someone was acknowledging that not all women who work out are doing so to lose weight—and, hey, maybe I’d finally, once and for all, learn what kind of figure I actually had. But when the advice focused on “creating curves,” I was confused: I'm not particularly busty, but lacking curves has never been my problem. In fact, since muscles generally are not shaped like squares but instead are gently sloping, I probably have more curves than I did before I started lifting weights.

All the arguments I've made before about "dressing for your figure" apply to "athletic." For starters, it’s meaningless: Some magazines use it to mean “broad-shouldered and thick-waisted,” others use it to mean “big thighs, little hips,” others use it to mean “naturally slender and small-breasted.” The one thing they always say is to “create curves”—something I don’t think, say, Jennie Finch or Gabrielle Reece ever worried about. (Webster’s does lists mesomorphic as one of the definitions of athletic, and while I’m appropriately skeptical of constitutional psychology, the ectomorph/mesomorph/endomorph typing comes in handy when discussing basic body types. But that’s not usually what’s being discussed on these pages, and within those classic types there’s enough cosmetic variation that it doesn’t really belong on a “dress your body”-type of page anyway.)

But the “athletic body” deserves a bit of special treatment. For unlike being an apple or an hourglass or whatever, being athletic is something you choose. You might not be able to choose how your activities shape your body, but you choose to be athletic. And while I understand that you might not always want to be showcasing your body, I also don’t know of any female athletes—professional or just gymgoing ladies—who seem to try to conceal what their activities have brought them. You don’t see swimmer Natalie Coughlin covering up her developed shoulders as Rent the Runway would say she should (“detract from wider-built shoulders” with a one-shouldered dress, they advise); you don’t see Lisa Leslie trying to cover her rippling muscles when she’s on the red carpet.

More important, though, the idea of the “athletic body” ignores the enormous range of sports and the athletes who play them. Different sports work better with different bodies, as beautifully photographed by Howard Schatz in Athlete, a collaboration with Beverly Ornstein that depicts the enormous range in athletes’ bodies, from high jumper Amy Acuff to gymnast Olga Karmansky to weightlifter Cheryl Haworth. And even if we make room for the prototypical body of each sport, as Ragen at Dances With Fat—whose blog roots are in showing the world that a 284-pound dancer is, in fact, a dancer (she's won three National Dance Championships)—asked us last week, “When did being an athlete become more about how a body looks and less about what it can do?”

And, at its heart, that’s what ails me about the “athletic” body type as shown in women’s magazines. I don’t lay claims to be an athlete. But learning that I could develop muscle and look “athletic” was enormously empowering to me. I have worked hard to be able to do 40 push-ups (okay, I haven’t done 40 push-ups for a while, but I could at one point, I swear!), and the muscles that come with it are emblematic of that growth. Yeah, yeah, I struggle with body image like everyone—but my “athletic” build isn’t among those struggles. (In fact, when I look at my hard-won muscles and have a negative thought about them, that’s evidence that something else is going on that I need to examine.) My body does not do anything extraordinary; in fact, it just does what it’s supposed to do. But my athletic body is a triumph over so many painful memories: defiantly munching cookies during my final tennis lesson because I was afraid I’d look foolish on the court, pretending to twist my ankle during the 50-yard dash on field day so I didn’t have to suffer the indignity of coming in last, teachers asking if I was okay when my face would still be beet-red 30 minutes after gym class.

Listen, I can’t say I “love my body,” all right? But I love what athleticism has brought to me, and I treasure the ways it’s visible on my body. My athletic body doesn’t need anyone’s fashion advice. It doesn’t need anyone’s categorization. It does not need to be dressed around, typed, or even acknowledged. It just needs to move.

—felt like torture, and I had to do it every year from grades 6-9, and I played sick every year until I realized I’d just have to do it on a day when the rest of the class was playing touch football or something and therefore able to watch me run The Mile, which was even worse.

I thought that way all my life—a singular aqua aerobics class my final semester of college notwithstanding, in order to "round out my course load"—until 2002. I'd broken up with a boyfriend, and it was one of those breakups that makes you wonder if you will ever be okay again, where being alone feels excruciating because you’ve cried all you can and you don’t know what else to do. Being on the subway felt okay for some reason, and since I wasn’t so despondent as to just ride the rails all day with no purpose, I took the opportunity to travel to gyms in the farthest reaches of all five boroughs to take advantage of their guest passes. (Plus, then I’d get really fit and toned and lithe and show him!)

The first time I entered a gym, it was in the Bronx, which I’d specifically chosen because I didn't know anyone who lived in the Bronx, so nobody I knew could possibly witness my fumbling around with the machines. I sat down at every machine in the place and read the directions so that the next time I went to a gym that would presumably not be in the Bronx, I wouldn’t look like a total fool. I stayed there for four hours.

Guest pass after guest pass, I worked my way through the city, and after a couple of months I realized that it was helping in ways beyond dealing with the breakup. My mood was improved, for one. My body, which hadn’t felt particularly out of shape before, began to feel...better. Like things were just working right. I was gaining confidence by knowing how to use the machines and free weights, and to my surprise I was finding that I was quickly able to up how much weight I was lifting—and, in fact, that I was lifting more weight than most of the other women on the floor.

And then there were the muscles. I had enough fat on me that it wasn’t visible for a while, but I could feel my arms getting more and more solid every week. Shaving my legs suddenly invited hazard because there was now a sharp little tennis ball where a soft calf had previously been. I distinctly remember looking at myself in the mirror while washing my hands and freaking out because there were these things moving in my chest, these ripply creepy-crawly things underneath my skin—and realizing that was my upper pectoral muscles, which I’d never actually seen before. I mean, I was no Colette Nelson, and you probably wouldn’t even have looked at me and called me “buff.” But I was distinctly more muscular than I’d ever been, and I’d even say I looked more muscular than the average woman of my age.

It turns out that my body actually is rather athletic. I still can’t catch, throw, or hit a flying object (gym-class phobia sets in even if a coworker tosses me a pen), and I would hesitate to say that I’m even in particularly good shape. But I’m reasonably fit; I can run a few miles without stopping; I lift weights. I even did some somersaults a few years ago when I went through a krav maga phase. Compared to the kid hurling herself down the stairs in 1983, I’m Mary Lou Fucking Retton. And when this fact hits me—when I am energized instead of exhausted after a run, or when a fellow gymgoer asks me to spot him, or when my doctor tells me that my heart rate is in the zone of conditioned athletes—I feel the type of gratitude and relief you can only feel when you realize that something negative about yourself that you’d accepted as truth is, in fact, not.

So the first time I saw “athletic body” in the “dress your figure” pages of a women’s magazine, I got excited. Finally, someone was acknowledging that not all women who work out are doing so to lose weight—and, hey, maybe I’d finally, once and for all, learn what kind of figure I actually had. But when the advice focused on “creating curves,” I was confused: I'm not particularly busty, but lacking curves has never been my problem. In fact, since muscles generally are not shaped like squares but instead are gently sloping, I probably have more curves than I did before I started lifting weights.

All the arguments I've made before about "dressing for your figure" apply to "athletic." For starters, it’s meaningless: Some magazines use it to mean “broad-shouldered and thick-waisted,” others use it to mean “big thighs, little hips,” others use it to mean “naturally slender and small-breasted.” The one thing they always say is to “create curves”—something I don’t think, say, Jennie Finch or Gabrielle Reece ever worried about. (Webster’s does lists mesomorphic as one of the definitions of athletic, and while I’m appropriately skeptical of constitutional psychology, the ectomorph/mesomorph/endomorph typing comes in handy when discussing basic body types. But that’s not usually what’s being discussed on these pages, and within those classic types there’s enough cosmetic variation that it doesn’t really belong on a “dress your body”-type of page anyway.)

But the “athletic body” deserves a bit of special treatment. For unlike being an apple or an hourglass or whatever, being athletic is something you choose. You might not be able to choose how your activities shape your body, but you choose to be athletic. And while I understand that you might not always want to be showcasing your body, I also don’t know of any female athletes—professional or just gymgoing ladies—who seem to try to conceal what their activities have brought them. You don’t see swimmer Natalie Coughlin covering up her developed shoulders as Rent the Runway would say she should (“detract from wider-built shoulders” with a one-shouldered dress, they advise); you don’t see Lisa Leslie trying to cover her rippling muscles when she’s on the red carpet.

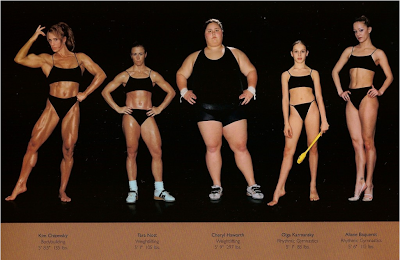

From Athlete by Howard Schatz and Beverly Ornstein

More important, though, the idea of the “athletic body” ignores the enormous range of sports and the athletes who play them. Different sports work better with different bodies, as beautifully photographed by Howard Schatz in Athlete, a collaboration with Beverly Ornstein that depicts the enormous range in athletes’ bodies, from high jumper Amy Acuff to gymnast Olga Karmansky to weightlifter Cheryl Haworth. And even if we make room for the prototypical body of each sport, as Ragen at Dances With Fat—whose blog roots are in showing the world that a 284-pound dancer is, in fact, a dancer (she's won three National Dance Championships)—asked us last week, “When did being an athlete become more about how a body looks and less about what it can do?”

And, at its heart, that’s what ails me about the “athletic” body type as shown in women’s magazines. I don’t lay claims to be an athlete. But learning that I could develop muscle and look “athletic” was enormously empowering to me. I have worked hard to be able to do 40 push-ups (okay, I haven’t done 40 push-ups for a while, but I could at one point, I swear!), and the muscles that come with it are emblematic of that growth. Yeah, yeah, I struggle with body image like everyone—but my “athletic” build isn’t among those struggles. (In fact, when I look at my hard-won muscles and have a negative thought about them, that’s evidence that something else is going on that I need to examine.) My body does not do anything extraordinary; in fact, it just does what it’s supposed to do. But my athletic body is a triumph over so many painful memories: defiantly munching cookies during my final tennis lesson because I was afraid I’d look foolish on the court, pretending to twist my ankle during the 50-yard dash on field day so I didn’t have to suffer the indignity of coming in last, teachers asking if I was okay when my face would still be beet-red 30 minutes after gym class.

Listen, I can’t say I “love my body,” all right? But I love what athleticism has brought to me, and I treasure the ways it’s visible on my body. My athletic body doesn’t need anyone’s fashion advice. It doesn’t need anyone’s categorization. It does not need to be dressed around, typed, or even acknowledged. It just needs to move.