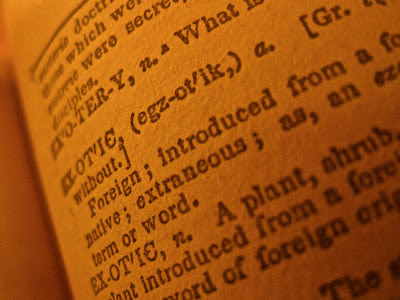

Exotic, in its most basic form, means to belong from somewhere else, stemming from the Greek exotikos (“from the outside”). Only 30 or so years after its English coinage in the 1590s, it came to mean not literally foreign, but psychologically so: alien, unusual, unfamiliar. It was mostly applied to plants and objects for a couple hundred years, until the rapidity of trade gave common people the ability to look exotic through adornment. In the early 20th century, all one had to do to be exotic was dress the part, whether it’s a gown of rose-colored silk or an astrakhan cap, or simply wearing one’s hair in an unusual manner. One didn’t organically look exotic; one became exotic, either through affect, clothing—or, perhaps, sensualism. Exotic dancing to mean striptease has been used since the 1940s, presumably evolving from the term’s general use to mean any wild dance performed to an unfamiliar beat. Add in fanciful, “Oriental” costumes, and one has exotic dance: Mata Hari’s performances were labeled exotic dancing more than 20 years before it came into common use. Even as late as 1947, Life was duly defining the term: “Exotic dancer in the nightclub trade means a girl who goes through a few motions while wearing as few clothes as the cops will allow in the city where she is working.” But the magazine was prescient in its use, applying it seven years earlier to dancer Carmen d’Antonio, who was half-Italian, half-East Indian.

That usage of exotic was prescient in another way, for somewhere along the line, exotic went from describing a consciously cultivated look to describing something its bearer could hardly strip away: race. Exotic became code for dark-skinned women of various ethnicities: black women (Naomi Campbell, Beverly Peele, Sade), Latina women (Selena), Asian women (Tina Chow, Joan Chen). It’s no coincidence that this move happened in the 1960s and 1970s: The shift of exotic from describing costume to describing skin color and features runs roughly parallel to women’s shifting roles in America. If the beauty myth rose to make sure that newly liberated women didn’t get too much actual power and were left pecking around for crumbs, the use of exotic morphed to make sure that women of color didn’t tap into their share of the crumbs. Just as quickly as women of color began to rise in public visibility and power, they were quickly repackaged as sexualized versions of the real women who lay beneath; the same year Shirley Chisholm began planning her presidential bid, the world met Pam Grier. Between civil rights and feminism, someone had to find a way to neither deny the existence of women of color nor be permissive in their bid for power: enter exotic. In 1950, a white woman could don a turban to become exotic; it was harmlessly dashing, a way to pad one’s cage with ornate silk instead of cotton for the day. But once that cage opened up, we were left with a perfectly good word that could serve as a cursory nod to women of color—hell, it’s a compliment, right?—while simultaneously keeping the cage’s door wide open for any exotic lasses who might want to enter.

It’s not terribly hard to see why exotic is problematic: In the States, white women are still perceived as neutral; dark-skinned women are the Other. For something to be exotic, by definition it must be the Other. So with exotic—which is usually used in an ostensibly positive sense, to describe a woman with striking beauty—we’re also looking sideways at its target, the message bearing the subtext of “You’re not from around here, are you?” And encoded in not being from around here is, Your beauty will never match our values. As LaShaun Williams at MadameNoire puts it about the “otherness” of being exotic: “Other than what? The set of standards that define true beauty. She is somehow beautiful without being ‘beautiful.’”

Yet while exotic neatly performs its function of divide-and-conquer, it’s also used to express anxiety about race and categorization, particularly when applied to mixed-race women. And boy, has it ever been applied to mixed-race women: Raquel Welch (Bolivian and British), Salma Hayek (Lebanese and Spanish), Sade (Nigerian and British), Kimora Lee (Korean, Japanese, and African American), Jessica Alba (Mexican-Canadian-American) and Kim Kardashian (Armenian-American) have all been called out as looking exotic, as have multitudes of self-identified black women with mixed backgrounds whose skin may be dark but whose features look largely European (Tyra Banks, Halle Berry).

Certainly exotic is better than what so many ethnically ambiguous people hear: “What are you?” (As Kerry Ann King, a dance instructor whose ancestral tree ranges from Sicily to Africa to the Jewish diaspora, put it, “I’ve always wanted to say, ‘A Gemini.’”) And if the 2011 Allure beauty survey is to be believed, mixed-race women are now not just exotic but downright beautiful, with 64% of respondents saying that people of mixed backgrounds represent the epitome of beauty. This report would be encouraging if it weren’t for what’s encoded in the photo shoot that followed the survey results: an anemic rainbow of mixed-race women who, save for skin tones and full lips, represent the “new beauty.” Being exotic was never really about being different; it was about being different in the right way. Be the Other, but not too much so, 'kay? It’s a point emphasized in Hijas Americanas, an exploration of Latina women, beauty, and body image, in which author Rosie Molinary writes of a friend who once told her she would be “so exotic-looking” if she just had a different eye color. “I wasn’t exotic enough to be interesting,” Molinary writes. “Just different enough to not be interesting.” In fact, today’s poster child for exotic, Brazilian model Adriana Lima, hits exactly that note: tawny skin, a cascade of shiny dark hair, and sparkling aquamarine eyes.

It’s the designation of Lima—who fits the beauty imperative in every way—as exotic that makes me wonder what exactly we mean with the word, and a prolific listmaker who goes online by Kawaii has wondered the same thing. I’m uncomfortable with most discussions that parse out any individual women’s looks with a fine-tooth comb, but the discussion at her list of celebrities who are “Classic Looking, NOT Exotic” is intriguing at points: It brings to light that the definition of exotic could easily go beyond the Other to include what is perceived as truly rare—and that by the list-maker’s definition, Adriana Lima shouldn’t really cut it. Being Latina doesn’t make Lima exotic, Kawaii argues; she’s a classic beauty by Euro-American standards, but has been (mis)construed as exotic simply because of her ethnicity. “Your coloring doesn’t make you exotic, it makes your coloring exotic,” writes our curator. She asks why white women with unconventional features aren’t usually considered exotic—Lauren Bacall, Taylor Swift—supplying her own answer (race is still the defining factor of the Other) but still pressing for an objective determination of what makes someone exotic.

And in some ways, of course, that’s impossible: We define exoticness based on our own perspective, and there’s really no other way to do it, because the very definition of exotic relies upon being unusual. But when we use exotic, we’re making assumptions based not only on our own “usual” but on the “usual” of those around us. Most of us understand that we’re all going to read beauty differently from one another, leading us to deploy terms like hot or cute. But with exotic, there’s a shared understanding: If I don’t believe that your baseline of what constitutes the exotic will be the same as mine, using the word makes no sense. To use exotic is to assume dominance. Exotic says as much about the speaker as it does the subject. Actually, it says more.

___________________________________

For more Thoughts on a Word, click here.