No.

The Zen koan—a paradoxical statement or dialogue used as a meditative tool by Zen practitioners—has a number of aims, if one is allowed to “aim” in Zen, which one probably isn’t. (I wouldn’t know; I used to say I was “agnostic” until I realized I was really just apathetic. But permit me to like the idea of Zen Buddhism, okay?) One aim of these riddle-like phrases is exhausting the intellect, for how can one respond analytically to the question of whether a dog has Buddha-nature, especially if the proper answer is understood to always be no? Another aim is to relax the will, allowing the mind to operate on an intuitive level.

But it’s one of the koan’s tertiary goals that interests me the most: dissolving the duality of subject and object. In fact, that’s sort of the idea behind what’s probably the most famous koan, even if most people who know it (myself included, until last week) don’t know what a koan is: Two hands clap and there is a sound. What is the sound of one hand? The sound of one hand clapping is the subject and object being unified, and unified in such a way that it’s not simply a twofer but something else entirely, something outside of the construct of subject and object (and, I suppose, outside the construct of sound). In seeking insight through the koan, the practitioner, instead of seeking an answer separate from oneself, is the koan. The subject and the object are the same.

The relationship between subject and object lies at the core of our relationship with beauty. The most obvious example is that women play dress-up to turn ourselves into objects under a system where men are the subjects. But in the new-ish strain of thinking about beauty, women have reconfigured beauty work not as a way to keep themselves objectified but as a liberation or expression of the “true self.” It’s a neater, more progressive response to objectification on the behalf of men, yet using “but I do it for me!” as the end to the conversation would be a mistake. For then, the relationship merely shifts from making oneself into an object for others to making oneself an object for ourselves. When I take satisfaction in how I look, I am still observing myself as an object. Even if there’s nobody else in the room, even if I’m not imagining myself being observed, I am still being observed. I might be both subject and object, but they remain separate roles, even if the actor—me—is one creature.

Unification, then, seems a worthy goal, Zen-wise. Not in the sense of embodying both subject and object, but rather dropping the division between the two in order to shift the act of observation into the act of existing. It’s a goal I’ve stalked for some time; in fact, it was the driving force behind my “mirror fast,” this idea of severing the loop of self-monitoring, self-objectification, self-observation, self self self, in favor of something that’s paradoxically more organic and more elusive. Have I achieved it? Does a dog have Buddha nature?

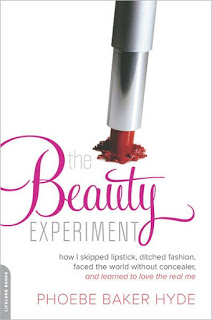

Though it turns out I’d heard a handful of Zen koans before—the one-hand-clapping bit; if you see the Buddha, kill the Buddha—it wasn’t until I read Phoebe Baker Hyde’s The Beauty Experiment: How I Skipped Lipstick, Ditched Fashion, Faced the World Without Concealer, and Learned to Love the Real Me that I learned what they actually were. Baker Hyde’s use of the koan shows up about two-thirds of the way through the book, when she begins to question the very meaning of beauty and its role in her personal narrative—but for me it was the climax, and in a way it’s a metaphor for the paradox the entire book presents. The story of her year spent performing next to no “beauty work”—makeup, hairstyling, mani-pedis, most depilation, clothes shopping—in order to find out what would happen if she stopped playing the beauty game altogether, the book is a good deal less tidy than the subtitle implies, and that’s a good thing. (In fact, when I first read the title I was expecting something a whole lot more clichéd. It’s nice to be wrong.)

With each of the book’s paradoxes, Baker Hyde’s storytelling bests itself, giving the reader more than what its framework initially seems to allow. The subtitle is the first paradox—“learning to love the real me” isn’t exactly what Baker Hyde experiences, though she does emerge from her yearlong experiment better off. Another is the way the author frames her format in the introduction: With each chapter split into before-and-after “snapshots” of her life during the experiment, then a fast-forward to four years after its conclusion (during which we see not a tranquil Baker Hyde merrily rolling along, but rather a woman continuing to evolve), she writes that the book is essentially a tale of two women. Yet the book’s nuanced approach reveals the opposite. By gradually learning to suspend judgment of herself as “lesser” before or during the experiment and “greater” after, we see that that the elliptical possibilities of being one person are broader than any quick-and-dirty psychic makeover could hope for.

There’s plenty of reasons to recommend this book: Baker Hyde’s skilled storytelling, the glimpses into her relationship with her husband and the culture surrounding her (she did the experiment while living in Hong Kong, which serves the focus here nicely instead of being a distraction), the—as ladymag editors would put it—“relatability” of the narrator, the interjected sociological bits derived from a survey she conducted on beauty and self-image. As with the subtitle, even the elements I was initially dubious of eventually proved their worth: One intended arm of the experiment was to funnel money that would have been spent on appearance into philanthropy, something that could have easily turned into a tsk-tsking of beauty-as-selfishness. Instead of implicitly scolding her readers (who are presumably not beauty-fasting), though, Baker Hyde tells us how this part of the project continually eludes her; she neglects to write down expenses she would have incurred were it not for the experiment, and she also “forgets” to tell her husband about her philanthropic goal. Looking at beauty work through her lens of her nearly forgotten do-gooding, we see how just as some reasoning for beauty work we don’t actually want to perform wears thin, some reasoning for liberating ourselves from beauty work might verge on justification. (She does wind up making a philanthropic donation by book’s end, of course.)

But the biggest reason to recommend The Beauty Experiment is, to bring it back to the koan, its Zen-like quality. Not so much that the author or reader reaches a place of Zen bliss, but rather that the nature of challenging beauty in our culture leads one not to a black-and-white resolution, but to a place of conscious awakening. For the sake of sales and marketability, the book is necessarily packaged using the go-girl tone of the subtitle. But it quickly becomes clear that Baker Hyde wasn’t seeking tidy, snipped-off conclusions—or rather, if she was seeking them, she didn’t find them, much to the reader’s benefit. Where I expected an arc of insecurity to security, there was a cyclical tale of relationship dynamics, liberations coexisting with expectations, mixed responses from friends, and cultural pressures. Where I anticipated serenity at experiment’s end, I instead found reverse culture shock—which then makes the actual moments of serenity, like her first post-experiment outing with friends, all the more important. (Full disclosure: I might also have been particularly tickled that during her own brief “mirror fast” in the midst of her larger experiment, she fingers the exact same John Berger passage I did in my prelude to my own mirror abstinence, and also dips into its connection to the flow state. Like minds, it seems, enjoy playing guinea pig on ourselves.)

Just as beauty doesn’t offer us easy solutions, the approaches to beauty that initially seem to be neat wind up being anything but. Twenty years after The Beauty Myth, women (and marketers) are more schooled in the political framing of beauty work, yet that knowledge often shows up in conversations as the platitude “I do it for me.” An early pseudofeminist argument I used to make about makeup-as-play fell flat when I realized very little of my beauty work had anything to do with imagination; at the same time, I began to see that my shame about literally applying concealer to the parts of myself I was uncomfortable with needn’t be shameful at all. There are no easy answers for our most important questions about beauty and femininity, and where I once found that frustrating, I now find it freeing—for if answers or solutions don’t come easy, maybe searching for them in vain isn’t the path to be on after all.

The recent New York Times “debate” on makeup and self-esteem—which, incidentally, Baker Hyde participated in—frustrated many of us who write about beauty. The elegant voicing of those frustrations, from Autostraddle to Jezebel to Wild Beauty, are proof positive of my only real beef with the Times package: The relationship between makeup and self-esteem is too complex to be boiled down to an either-or query. The dialogue requires nuance, a suspension of judgment, and a stethoscope held tightly to the pulsing truths we announce every time we walk out the front door. My wish to participate in that sort of conversation is why I write about beauty; if you’re reading this, it’s at least part of why you read about beauty. I wouldn’t presume to know why any writers choose beauty (or anything else) as their topic, so I won’t try to say that Baker Hyde’s devotion to the complexity of the beauty conversation is why she penned The Beauty Experiment. What I can say is that the riddle of beauty is rarely as well-articulated as it is here.