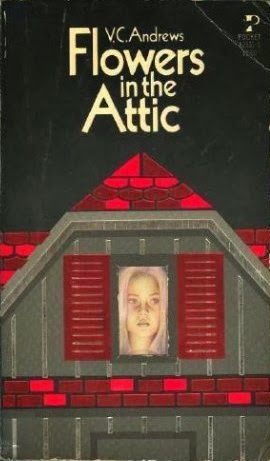

Yes, I’m serious. Flowers in the Attic—a.k.a. “The book that made teenage girls look sideways at their brothers and shudder,” as my similarly besotted pal Lindsay put it—wasn’t originally marketed as a young adult book when it was first printed in 1979, but it soon found its niche in the hearts of pubescent girls across the land. (And now it’s popularly acknowledged as a YA book; in fact, my library categorizes it as such.) It hit bestseller lists within two weeks of its publication, and the popularity of that book and the numerous other works by V.C. Andrews** that followed didn’t dwindle for years—in 1990, V.C. Andrews was still the second-most-popular author among teens.

I was one of those teenagers, and maybe you were too. I’d grown up on a steady supply of classics and earnest Newbery award-winning books for children and young adults, so it wasn’t like I was deprived of good literature. But come the sophisticated age of 12, I was ready for something juicier than Tom Sawyer kissing Becky Thatcher, and I moved straight into—spoiler alert, here and throughout—brotherfucking. And, you know, I knew it was trash, but damn if I didn’t stay up nights sixth through ninth grade blazing through the entire Flowers in the Attic Dollanganger series, followed by the Casteel series, followed by the Dawn series, followed by My Sweet Audrina, which I thought was lame*** and then I stopped. But when I heard that Lifetime was premiering a new**** Flowers in the Attic movie this Saturday, I went back for a reread, and thus, my declaration that Flowers in the Attic Is the Best Book Ever.

And here’s why.

1) The incest plot was hot.

Which is not to say that girls actually want to sleep with their brothers / sisters / uncles / cousins / parents / etc. It’s not even to say that girls fantasize about it in great numbers. But consensual incest caters to the nascent desires of many a pre/teen girl—that is, girls who aren’t yet sexually active, but who are beginning to think in terms of sexuality and have erotic impulses. A 12-year-old who has yet to be kissed might well be simultaneously drawn to and repulsed by the thought of sex—and what would make it a mentally “safe spot” where she could feel aroused and not repulsed? A known, loving, nonthreatening partner. That is...a brother. Not her own brother, of course; I’m guessing most girls would be repulsed by the thought of actually kissing her own brother. But with Flowers in the Attic, the teen reader is aligned with protagonist Cathy by dint of being a girl. She gets to experience the thrill of sex without having to entirely shed any vestiges of “eww boys,” because she knows that “her” brother (that is, Chris, Cathy's brother) is a loving, nurturing person who is, above all, safe. So by “becoming” Cathy, the reader is able to experience sex—which, if memory serves, the average early adolescent sees as a combination of forbidden and arousing—in a way that’s both.

Consensual incest is actually a recurring theme in Gothic novels (“the perfect linking of the most desirable object with the prohibited object”), and it showed up in the work of one of the most-read feminine***** erotica writers (Anaïs Nin, whose incest erotica was published just two years before Flowers in the Attic). It’s actually a surprise that there aren’t a whole lot more Gothic YA books with brother bangin’. Of course, the whole “brothers are safe” thing is complicated just a bit by the wee matter of consent. Chris and Cathy’s major sexual interlude begins with this:

… “You’re mine, Cathy! Mine! You’ll always be mine! No matter who comes into your future, you’ll always belong to me! I”ll make you mine...tonight...now!”

I didn’t believe it, not Chris!

And I did not fully understand what he had in mind, nor, if I am to give him credit, do I think he really meant what he said, but passion has a way of taking over.

We fell to the floor, both of us. I tried to fight him off. We wrestled, turning over and over, writing, silent a frantic struggle of his strength against mine.

It wasn’t much of a battle.

Two pages later, Chris is quick to offer the world’s most awful/awesome apology (“I didn’t mean to rape you, I swear to God”). But Cathy is just as quick to clarify that he didn’t rape her. “I could have stopped you if I’d really wanted to. All I had to do was bring my knee up hard… It was my fault too.” Yet the pretense that there was force involved may well have helped girls derive pleasure from it—“good girls” don’t actively want to have sex, after all. But if you’re simply overpowered, then you didn’t want it, it just happened. Applied to real life, this is terrible logic (in fact, it’s rapist logic); applied to the fantasy life of girls who have desires but not the know-how to give them form even in her imagination, it makes some sort of sense. Rape fantasies aren’t uncommon for women to have; about 4 in 10 women have them, with a median frequency of once a month. I couldn’t find any numbers about rape fantasies among girls/teens, but my hunch says that the idea of having to have sex whether you want to or not is probably far more appealing to someone who hasn’t yet learned how to express her sexual agency.

The first time I floated this girls-like-incest-fantasies bit out loud, one woman pointed out that for a good number of girls, rape and incest are realities, and that eroticizing them reinforces the idea that there’s something sexy about nonconsensual sex. (Keeping in mind that while consensual incest does happen, many survivors of coercive incest convince themselves their abuse is quasi-consensual, as a survival tactic.) I agree, at least in the sense that popular culture is a part of rape culture, which then colors the idea of what rape is (and—surprise!—usually not in a way that is helpful to its victims). But that’s not what’s going on in Flowers in the Attic. (Later “V.C. Andrews” novels, perhaps, but that’s a different post.) It’s in the realm of fantasy—it’s even constructed as such within the book. As literature professor Cynthia Griffin Wolff writes of earlier Gothic work, part of the hallmarks of Gothic literature is “a set of conventions within which ‘respectable’ feminine sexuality might find expression.” It’s understood by the reader as a way to get to read utter filth with a sort of “free pass” for wanting to do so in the first place. Case in point: When I read it as an adult, I found that I’d erased any rapey overtones from my memory of reading it as a kid. I saw it for what it was, and judging from the way my friends talked about it at the time, they did too. Nobody in their right mind would hand it to a young rape victim as a depiction of her experience—read as such, it’s horrific (“It was my fault too”?). But that’s not how it’s read by its readers, I don’t think. (Of course, when I read this book the first time, I hadn’t experienced a whit of sexual trauma; perhaps if I had, my memory of it would be different. I can only go off my own experience here.)

Point is: Girls don’t want to be raped, any more than they want to sleep with their brothers. But are there elements of it that appeal to the V.C. Andrews target demographic beyond the mere taboo? Yeah.

2) It lets you hate the mother but still love your own.

2) It lets you hate the mother but still love your own.

You know those goody-two-shoes YA novels where the protagonist and her mother might fight but deep down there’s a Very Special Connection? V.C. Andrews offers an ear-shattering Screw that and gives the reader every excuse to seriously hate on Cathy's mother, Corinne. SHE KILLED CORY, I mean, come on. Now, my mom and I have always had a pretty good relationship (I mean, I’m choosy about my guest bloggers, and here she is! Twice!). But our mother-daughter relationship took a definite downswing during my prime V.C. Andrews years. A catalogue of my mother’s sins circa 1987-89: She made me wear a hat and scarf in when it was a measly -18 outside (hats are for dorks!), she made me take a study skills course (study skills omg mom!), she enrolled me in a girls’ self-defense seminar against my will (on a Saturday, which is a weekend!), she made me read Charlotte Freakin’ Bronte (life is not school!), she wouldn’t buy me a Guess sweatshirt just because I wanted one (everyone but meee had one!), and she wouldn’t let me see Dirty Dancing (actually, I still think I’m right on this one).

Anyway. So while I never resorted to any “I hate you!” antics, there was definite tension, and it doesn’t require years of therapy to understand that part of it was my pubescent resistance to becoming anything like my mother—that is, a woman. Eager as I was to grow up, my fantasy of womanhood clashed hard against the reality of womanhood I saw in the form of the actual woman I knew best. In my head, being a woman meant, like, going to balls and wearing updos and going out with a different dashing suitor every night, but then here was this flesh-and-blood woman who was doing things like making taco salad. It wasn’t long before I woke up and started appreciating her and everything she did for our family, but at 12 I was just too self-absorbed.

Enter a mom who went from basically being a Christmas card to locking up her four children in an attic and slowly poisoning them while she...went to balls and wore updos and went out with dashing suitors. Corinne takes every bit of perfectly normal mother-daughter strife and balloons it into grotesquerie. She’s a nightmare in the truest sense—just as you might manifest everyday anxiety into the classic why-am-I-in-my-underwear dream, Corinne’s evil is an enormously exaggerated version of what a lot of girls might feel toward their mothers at that age, shown from the girl’s perspective. That includes love and adoration too—Cathy might need prompting at times, but she’s still willing to melt into Corinne’s arms for quite some time after Corinne locked her away.

As Adrienne Rich writes in Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution, mother-hatred is interpreted as “a womanly splitting of the self, in the desire to become individuated and free. The mother stands in for the victim in ourselves, the unfree woman, the martyr.” Gee: split self, desire to become individuated and free, victim, martyr, sounds like a whole lotta 12-year-olds I knew. Cathy’s physical resemblance to Corinne is more than a handy plot point (not to detract from the awesome doppelganger subplot in Petals in the Wind******, but I digress); it’s an extension of this idea that mother is daughter, and daughter mother, as much as she wishes not to be. And it also leads to…

3) It depicts aspects of beauty that we don’t often see.

Plenty of books explicitly aimed at teens and preteens involve looks, but it tends to be some variation on the protagonist’s dissatisfaction. Maybe she doesn’t think she’s pretty (but some boy just might teach her otherwise!), maybe she’s jealous of her best friend’s looks, maybe she has a movie-moment makeover in which she sees herself as she wishes to be seen. The better of the YA set will deal with these in a more complex manner, but at best there’s ambivalence about whether or not the girl feels attractive.

Not so with Cathy: She’s a babe, and she knows it, and it isn’t because of any makeover. In fact, she has a disdain for artifice—when her brother tells her that if she develops an hourglass figure, she’ll “make a fortune,” she schools him on the dangers of corsetry. She takes sensual pleasure in herself: “[A]lways before I went to sleep, I spread my hair on my pillow so I could...nestle my cheek in the sweet-smelling silkiness of very pampered, well-cared-for, healthy, strong hair.” She waits until she’s alone and “then I stared, preened, and admired” herself in the mirror, for “Certainly I was much prettier than when I came here.” As for body image, when she talks of her dream of becoming a ballerina, she points out that “dancers have to eat and eat or else they’d be just skin and bones, so I’m going to eat a whole gallon of ice cream each day, and one day I’m going to eat nothing but cheese…”—a far cry from the prototypical YA-ballet-eating-disorder storyline. (I mean, eating a gallon of ice cream a day is an eating disorder, but whatever.)

_________________________________________

* Okay, seriously, it’s more like, Anna Karenina, Beloved, The Sun Also Rises, and then Flowers in the Attic. Or is it?!?!

Cathy takes pride in her looks, something that we cheer her on about, especially when she’s punished by the grandmother after she catches Cathy admiring herself naked in the mirror. (Naturally, the punishment befits the crime: She pours tar in Cathy’s long blond hair, forcing her to cut it off.) Pride isn’t the sin here—the sin, as the reader sees it, is all on the grandmother. In what other universe are girls cheered on for their vanity? Not just her pride or resilience with her body image or ability to recite “I’m beautiful just the way I am!” or whatever, but her downright vanity? It’s the cardinal sin of girldom, thinking you’re “all that.” But Cathy does it. The only “mean girl” around to side-eye her is the grandmother (“‘You think you look pretty? You think those new young curves are attractive?’” she hisses at Cathy), and obviously we’re going to be on Cathy’s side here. We freakin’ eat it up.

The leadup to Cathy and Chris getting all bow-chicka-bow-bow is less about anything that actually happens between them physically, and more about him seeing her (something her mother never does—Cathy totally freaks when Corinne brings her a bunch of “silly, sweet little-girl garments that screamed out she didn’t see,” none of which have room for her new curves). “[Y]ou look so beautiful. It’s like I never saw you before. How did you grow so lovely, when I was here all the time?” Chris says to Cathy upon catching her naked. The only other eyes on her as a woman are her own. Remember that whole “girls mature faster than boys” thing that turned out to be painfully true? Remember that sensation of wishing boys would just see you already? Yeah.

Andrews herself had experience with looks bringing a mixed bag of tricks: After suffering a severe fall as a teenager (which eventually landed her in a wheelchair), doctors didn’t believe that she was in pain, telling her she “looked too good” to be seriously hurt. Says Andrews of that age, “I was very pretty, and some fathers of my little girl friends made advances.” She never spoke publicly of anything abusive that might have happened, but it’s interesting to note that alongside the wording she chooses for Corinne when describing how she fell in love with her husband/half-uncle-half-brother: “I was fourteen years old—and that is an age when a girl just begins to feel her power over men. And I knew I was what most boys and men considered beautiful…” Girls are usually cautioned against playing with this particular kind of fire—as well they should be, given the potential fallout. But denying that there’s a lure to discovering one’s own appeal does girls a disservice, particularly when young women’s bodies are still the universal symbol for sex.

Okay, now that I’ve convinced you that Flowers in the Attic is the best movie ever, you should all watch Saturday’s premiere with me and live-tweet the whole damn thing. That’s my plan, at least, but I am not kidding when I say that if tweeting interferes with the sheer enjoyment of it I will turn off all devices except the television immediately. In any case, I’ll hop on the Lifetime hashtag and go with #badgrandma too. Join in!

_________________________________________

* Okay, seriously, it’s more like, Anna Karenina, Beloved, The Sun Also Rises, and then Flowers in the Attic. Or is it?!?!

** And by “V.C. Andrews” I mean both Flowers in the Attic author Virginia Andrews and ghostwriter Andrew Neiderman, who continued to write books under her name after Virginia’s death. Tracie Egan Morrissey interviewed him for Jezebel here.

*** Duh, of course it was lame. The first two lines of the Wikipedia entry about it: “My Sweet Audrina is a 1982 novel by V. C. Andrews. It was the only standalone novel without incest published during Andrews' lifetime.” Bo-ring!

**** As opposed to the old FITA movie with Victoria Tennant and Kristy Swanson, which was unfaithful to the book in the lamest possible ways (see also ***, above).

***** The literature scholars among you will likely not be surprised to learn this, but I was: There’s actually an entire genre of Gothic literature dubbed “female Gothic,” the hallmarks of which include ambivalent feelings toward female sexuality, and women being literally or symbolically motherless while simultaneously being shaped by patriarchal culture. For more on female Gothic—and for V.C. Andrews in particular—check out V.C. Andrews: A Critical Companion, which A) exists, and B) is now officially replacing Flowers in the Attic as The Best Book Ever. And now I’m absolutely serious—no, really, I am—it’s totally awesome and if you enjoyed this post at all you should at least skim it. Fascinating stuff.

****** Cathy dresses up just as Corinne did for a Christmas party 15 years earlier, then stuns the guests at the very same annual party by making a grand entrance as "Corinne" and revealing that she had kept four children locked away in the attic while she spent her evenings drinking from champagne fountains and slowly poisoning her kids with arsenic doughnuts. Then the mansion burns down, and Corinne winds up in an insane asylum. THE BEST.

****** Cathy dresses up just as Corinne did for a Christmas party 15 years earlier, then stuns the guests at the very same annual party by making a grand entrance as "Corinne" and revealing that she had kept four children locked away in the attic while she spent her evenings drinking from champagne fountains and slowly poisoning her kids with arsenic doughnuts. Then the mansion burns down, and Corinne winds up in an insane asylum. THE BEST.