For the second installment of a series on bodies and relationships, I'm pleased to be able to share the work of Emily Timbol, a blogger and author who writes faith, life, and humor essays. Her work can be found on the Huffington Post, The Burnside Writers Collective, xoJane, Red Letter Christians, Christianity Today’s Her.Meneutics, and RELEVANT magazine online. She’s also been a featured guest on Moody Radio’s Up for Debate, the Jesse Lee Peterson radio show, and the Something Beautiful podcast. Her first book, Two Words: Why Hearing “I’m Gay” Changed My Straight, Christian Life, is available now on Kindle, and paperback. You can find links to all her published works on her blog and on her Twitter, @EmilyTimbol. She can also be reached by email, at emily.timbol@gmail.com

____________________________________________________________

One of the stupidest quotes I’ve ever heard is, “Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels.” If you’re someone who buys into the dichotomy of being thin or being well-fed, taste is the last thing you care about. When I was at my thinnest, nothing tasted or felt good. When your body is the enemy, “good” isn’t something you feel.

Now, I’m fat. To Kate Moss, the originator of that quote, I was probably fat at my thinnest too, at 160 pounds, and I’m currently inhuman, at well over 200. To me now, the word fat is simply a descriptor, like blonde or tall, but back at my thinnest it was the worst combination three letters could make. Fat was to blame for my poor self-esteem, my lack of dates, and my typical teenage melancholy that I mistook for depression. It was all fat’s fault.

From the ages of 10-25, a good portion of my brain was devoted, at all times, to thinking about food. It never occurred to me that it was not normal, or healthy, to spend 18 hours a day thinking about peanut M&M’s. Or Cheetos, or that cheeseburger on the menu I wanted to order instead of a salad. If I wasn’t obsessing over food I couldn’t eat, I was obsessively hating myself for having eaten it—usually in a frantic, euphoric nighttime binge that would leave me feeling sick.

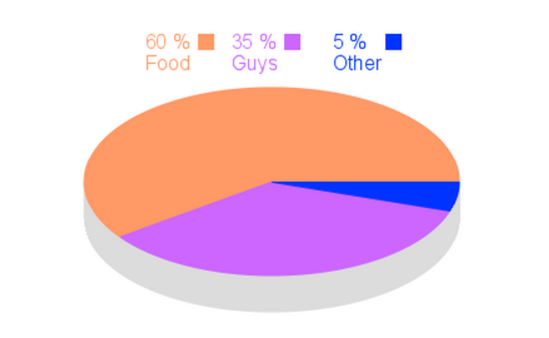

If my brain then was a pie chart (pie being a food I couldn’t eat) it would look like this:

The “Other” section represents the things that made me who I was, “on the inside.” Things like books, humor, politics, friends, and a passion for social justice. None of which mattered as much as food—or guys. It was them, really, who fueled so much of my youthful self-hatred. Always loving to hang out with me, always complaining about their girlfriends to me, sometimes even trying to sleep with me, but never, ever wanting to date me. This was never their fault, or my fault for liking them. It was fat’s fault. If I just could get the fat to go away, then these jackasses would magically like me back. That maybe guys didn’t like me because I didn’t like me, not because I wore a size 18, never crossed my mind.

“Emily, men are visual,” a close family member said to me. “That’s how they’re attracted, and I worry that if you never lose weight you won’t find a husband.” This was told to me more than once.

My best friend at the time once replied, after I revealed the name of the guy I had a crush on, “No, guys like that don’t go for girls as big as you.” She said it as matter-of-factly as if I had asked if there was food in my teeth.

It was settled. I had to lose weight in order for guys to like me. Not once did it occur to me that my body, as it was, any guy could like.

After my fourth week of The Master Cleanse, the last and craziest attempt I’d ever made to lose weight, I finally gave up. While gagging on the mere suggestion of drinking one more sip of maple syrup and cayenne, I thought, Why the hell am I doing this? Maybe it was the hunger (or cayenne poisoning), but all of a sudden it seemed like there was no reason to keep trying to force my body to be something it wasn’t.

Being thin wasn’t worth it. Having all of my thoughts consumed with food, exercise, and what I looked like suddenly seemed pointless. I wasn’t the kind of woman whose looks were her most important feature. I didn’t value attractiveness more than intelligence or wit. I wasn’t unhealthy in the slightest, according to my doctor. And damnit, I loved food.

The shift of priorities was surprisingly easy. It was as if I suddenly realized that the game I was trying so hard to compete in—the one where your social and romantic value is based on your looks—wasn’t mandatory; I could walk away from it at any time. I realized something else too: When you spend your entire youth and adolescence benched from the game because you're too fat to play, you see that the sidelines aren’t such a bad thing.

On the sidelines is where my personality flourished. Where my love of words grew, where I learned to make people laugh, and where I found some of the friends I hold dearest—friends who didn’t care that I was fat. The sidelines were where I learned to like who I was, something that wouldn’t have been possible if I’d stayed so focused on what I looked like.

I thought that leaving the game and giving up my near-lifelong quest to be thin meant making a choice between being attractive and hungry, or fat and happy. It wasn't so much that I chose to be fat; it was that I chose to be happy. I knew the work it took to be thin(ner). I spent years counting every calorie, writing down everything I ate, trying every new diet, and doing the math to make sure that nothing put between my lips was left unpunished. But choosing fat and happy wasn’t a choice made out of laziness; rather, it was a choice made because I was tired of hating my body—something I did no matter what the number on the scale said. What never once crossed my mind was that I could be fat, happy, and attractive. Like many people, I thought fat was always ugly, especially to men. I cared less about men, though, once I stopped hating myself. A great side-effect of learning to love myself was feeling less of a need for another person’s approval.

This didn’t make me any less shocked when a man I found attractive asked me out, a month after I gave up. I was skeptical of him at first. Tempted to write him off as a “chubby chaser” or some freak who found fat chicks amusing. An attractive man wanting to date me didn’t fit anywhere into my understanding of the rules.

It was after a couple dates with him—when my walls were still up, but I was feeling tempted to let them down—that I decided to go searching for his flaws. I started the place everyone does: Facebook. What I was most afraid of were the pictures of his exes. Not because I was threatened by them, but because I was afraid to be like them. A “them” I feared would look as hideous as I had previously felt. But as I clicked on their pictures, I was shocked to see that though they were all around my size, they were…pretty. The first woman I figured was an anomaly, or just took flattering pictures, but the second woman was equally attractive. Seeing them in succession made me realize that men exist whose type is “fat and pretty.” Those two things together was not something I’d believed in before. It’s not that I’d never seen a pretty, fat woman, it’s that I’d never thought one could be just pretty, not pretty*—the asterisk standing for, “if you weren't so fat.”

I started to look around me, and for the first time, instead of hyper-focusing on body parts I thought were attractive—flat stomachs, thin thighs, solitary chins—I saw whole women. Women who, at a size 12, or 18, or 10, were happy, loved, and content with their lives. These were not women who had “let themselves go”—they were women who chose to embrace their bodies at whatever size they were, instead of fighting to make them smaller. I wanted to be one of these women. I was one, as it turned out.

Allowing myself to accept that women could be attractive and fat allowed me to trust my (now-husband) when he complimented me. There’s nothing wrong with him either, and he’s not alone—there are men out there who find women of all sizes attractive and desirable. Attractiveness is subjective, not something you can point to on a chart. To claim that “all” men only find one type of body appealing is both myopic and offensive. Men, and women, are allowed to deviate from the standards of beauty society says is best. They’re allowed to be attracted to women who look like me.

Still, my fear was that if I allowed myself to eat what I wanted, I’d not just be fat, but gain hundreds of pounds. I was scared that if free to eat anything, I’d eat everything. Get so big that my husband would be equal parts turned off, and concerned about me. But this didn’t happen. My weight has been steadier in the five years since I stopped dieting than it was during the 15 years prior. That’s because when food stopped being “good” or “bad” and became simply food, it lost its power to control me. There’s no need to obsess over peanut M&M’s all day when you can eat them whenever you want. And being able to have them, made me want them less.

I didn’t lose any weight when I stopped obsessing over food. That didn’t matter. What was worth so much more than being able to fit into a smaller size was being able to go an entire day without the constant soundtrack of calories reverberating through my head. I was free to enjoy myself while cooking dinner, or going out to eat with my husband. It was just the two of us—not dieting meant there was no third entity present in our relationship, encroaching on my attention and time, demanding to be acknowledged. Being able to exist as a person who cared more about who I was, than what I looked like, allowed me to find love. Both with my husband, and myself.

I might not ever have a body that most people find attractive, but I have something more important—happiness. Happiness with myself, and with the man who loves me. All of me.

______________________________________

This is the second of a series on bodies and relationships. For more entries, click here.