What's going on in beauty this week, from head to toe and everything in between.

From Head...

Thin Mint lips: Girl Scout Cookie Lip Smackers! But what's with this "Coconut Caramel Stripes" flavor? You already yanked the rug out from under me with that "Samoa" jazz. Caramel Delight 4-eva!

...To Toe...

This little piggy went to fashion week: Fashionista's slideshow of models' feet on the runway is a lightly grody reminder that fashion ain't always glamorous (and that you're not alone in having fit problems).

Pediprank: Indiana governor Mitch Daniels went in for surgery on a torn meniscus and wound up with a pink pedicure. Dr. Kunkel, you old dog you!

...And Everything In Between:

"It's angled, like a diamond baguette": The rise of the $60 lipstick in the midst of a recession. Not sure about the "pragmatic" part of the term "pragmatic luxury," but what do I know? I just drink red wine, smack my lips together, and hope for the best.

Dishy: The flap surrounding the Panera Bread district manager who told the Pittsburgh-area store manager to staff the counter with "pretty young girls" was reported as a racist incident, since the cashier he wanted replaced was an African American man. But as Partial Objects points out, it may have been more motivated by sexism. To that I'd add that it's not just sexism and racism, but the notion of the "pretty young girl" that's at the heart of the matter here.

Give 'em some lip: American Apparel is launching a lip gloss line, with colors that will be "evoking an array of facets of the American Apparel experience." Names include "Legalize L.A.," which references the company's dedication to immigration reform, and "Intimate," an echo of the company's racy advertising aesthetic. Other shades on tap include "Topless," "Pantytime," "In the Red," "Jackoff Frost" and "Sexual Harassment in Violation of the Fair Employment and Housing Act Govt. Code 12940(k) Shimmer."

Music makers: Boots cosmetics line 17 commissions up-and-coming musicians to write and perform songs that align with the ethos of 17 products. As in, "You Might Get Stuck on Me" for their magnetic nail polish.

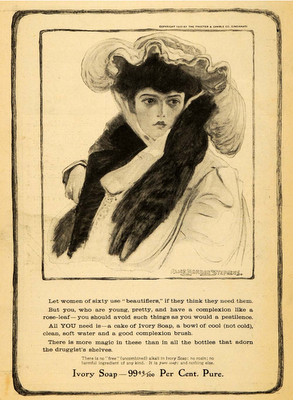

99% marketing: For its 132nd birthday, Ivory soap is unrolling a new ad campaign, which hinges upon it being A) nongendered, and B) soap. Revolución!

Baby fangs: Intellectually I should be against about the practice of yaeba, in which dentists in Japan artificially enlarge their lady patients' incisors to create a childlike appearance. But as someone who is genetically blessed with noticeably sharp and semi-crooked incisors, I'm basically all, I am gonna be huge in Japan.

Vaniqua'd: The active ingredient in Vaniqua—you know, the drug you're supposed to take if you have an unladylike amount of facial hair—is also an effective treatment for African sleeping sickness. Of course, the places where African sleeping sickness strikes can't afford to buy it. But hey, our upper lip is so smooth! (via Fit and Feminist)

La Giaconda: The Mona Lisa, retouched.

Beauty survey: Allure's massive beauty survey reveals that 93% of American women think the pressure to look young is greater than ever before. Am I a spoilsport by pointing out that every person who answered that question is also older than they ever were before? (Of course, the "hottest age" for women according to men surveyed is now 28, compared with 31 in 1991, so there may be something to it.) Other findings: Black women are three times as likely as white women to self-report as hot, and everyone hates their belly.

Gay old time: Jenelle Hutcherson will be the first openly lesbian contestant of Miss Long Beach—and she's going to wear a royal purple tux for the eveningwear competition. The director of the pageant encouraged her to sign up, and Hutcherson has been vocal about how she's reflecting the long tradition of diversity and acceptance in Long Beach. (Thanks to Caitlin for the tipoff!)

Miss World: In more urgent beauty pageant news, British women protest Miss World, and somehow the reporter neglects to make a crack about bra burning.

The freshman 2.5: Virginia debunks the "freshman 15," and then Jezebel reveals that the whole thing was an invention of Seventeen magazine, along with the notion that every single New Kid on the Block was supposed to be cute.

Ballerina body: Darlene at Hourglassy examines the push-pull between embracing and dressing large breasts (which she does beautifully with her button-front shirts designed for busty women) and her love of ballet. "By the end of the performance I wasn’t paying attention to anything but the movements. There was nothing to distract me from the dancers’ grace and athleticism. Would I have been distracted by large breasts on one of the dancers? Definitely."

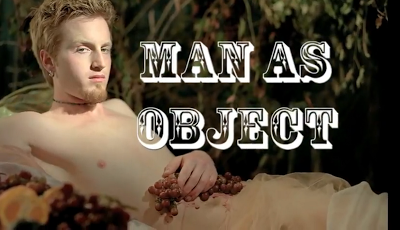

Subject/object: Prompted by this intriguing Man as Object exhibition in San Francisco, Hugo Schwyzer looks at the possibilities for desiring male imperfection. He's the expert here, both because of his research and his male-ness, but I can't help but wonder how much men have internalized the notion of male perfection. I have zero doubt that the focus on the body beautiful has impacted men, and certainly the tropes of masculinity are a reasonable parallel to the tropes of femininity. But there's always been more room—literal and metaphorical—for men of all varieties to be considered sex symbols. Everyone gawked when Julia Roberts paired up with Lyle Lovett, but even then there was talk of how he had "a certain quality." Save someone like Tilda Swinton—who, while odd-looking, isn't un-pretty either—when have we ever spoken of women in that way?

Am I the only one who thinks gigolo should be pronounced like it's spelled?: Tits and Sass has been looking for voices of male escorts, and lo and behold, Vin Armani to the rescue!

"Did my son inherit my eating disorder?": There's been some talk about how a mother with food issues can transfer that to her daughters—but Pauline wonders if she's passed down her eating disorder to her son. A potent reminder that boys internalize ED factors as well.

What you can't tell by looking: And along those same lines, Tori at Anytime Yoga reminds us shortly and sweetly that eating disorders of all forms come in a variety of sizes. This is enormously important: I'm certain that there are many women with eating disorders who don't recognize it because they don't think they fit the profile.

In/visible: Always glad to see celebrities acknowledge that looking they way they look actually takes work, à la Jessica Biel here: "My signature style is a 'no-make-up make-up' look, which is much harder than people think." Well, probably not most women who do no-makeup makeup, but whatevs.

Touchdown: This BellaSugar slideshow of creative makeup and hairstyle from NFL fans in homage to their favorite teams is a delight. I could care less about football itself (I finally understand "downs," I think) but I think it's awesome that these people are showing that there are plenty of ways to be a football fan, including girly-girl stuff like makeup. (IMHO, football fans could use a PR boost right about now. Seriously, Penn State? Rioting? You do realize your coach failed to protect multiple children from sexual assault, right?)

Face wash 101: Also from BellaSugar: There were college courses on grooming in the 1940s?!

She walks in beauty like the night: A goth ode to black lipstick, from XOJane.com.

Muppets take Sephora: Afrobella gives a rundown of the spate of Muppet makeup. Turns out Miss Piggy isn't the first Muppet to go glam.

Love handle: The usual story is that we gain weight when we're stressed or unhappy because we're eating junk food to smother our sorrows—but Sally asks about "happy body changes," like when you gain weight within a new relationship.

Locks of love: Courtney at Those Graces on how long hair can be just as self-defining as short.

_____________________________________

*Numerology field day! More significantly, Veterans' Day. Please take a moment to thank or at least think of the veterans in your life—you don't have to support the war to support soldiers. It's also a good time to remember that not all veterans who return alive return well: The Huffington Post collection "Beyond the Battlefield" is a reminder of this, particularly the story of Marine widow Karie Fugett, who also writes compellingly at Being the Wife of a Wounded Marine of caring for her husband after his return from Iraq; he later died from a drug overdose.

While most combat roles are still barred to women, there are plenty of female veterans—combat, support, and medical staff alike. Click here to listen to a collection of interviews from female veterans of recent wars, including Staff Sergeant Jamie Rogers, who, in When Janey Comes Marching Home, gives us this reminder of the healing potential of the beauty industry: "I went [to the bazaar near Camp Liberty in Baghdad] often to get my hair cut. They had a barber shop and then they had a beauty salon. It was nice to go in and it was a female atmosphere. It was all girls. You could put your hair down, instead of having it in a bun all the time, get it washed. It was just something to escape for a while, get away from everything. And it was nice to interact, and the girls were always dressed nice and always very complimentary: 'You have such beautiful...' and I don't know if it was BS, but it felt good that day. That was a good escape."

From Head...

Thin Mint lips: Girl Scout Cookie Lip Smackers! But what's with this "Coconut Caramel Stripes" flavor? You already yanked the rug out from under me with that "Samoa" jazz. Caramel Delight 4-eva!

...To Toe...

This little piggy went to fashion week: Fashionista's slideshow of models' feet on the runway is a lightly grody reminder that fashion ain't always glamorous (and that you're not alone in having fit problems).

Pediprank: Indiana governor Mitch Daniels went in for surgery on a torn meniscus and wound up with a pink pedicure. Dr. Kunkel, you old dog you!

...And Everything In Between:

"It's angled, like a diamond baguette": The rise of the $60 lipstick in the midst of a recession. Not sure about the "pragmatic" part of the term "pragmatic luxury," but what do I know? I just drink red wine, smack my lips together, and hope for the best.

Dishy: The flap surrounding the Panera Bread district manager who told the Pittsburgh-area store manager to staff the counter with "pretty young girls" was reported as a racist incident, since the cashier he wanted replaced was an African American man. But as Partial Objects points out, it may have been more motivated by sexism. To that I'd add that it's not just sexism and racism, but the notion of the "pretty young girl" that's at the heart of the matter here.

Give 'em some lip: American Apparel is launching a lip gloss line, with colors that will be "evoking an array of facets of the American Apparel experience." Names include "Legalize L.A.," which references the company's dedication to immigration reform, and "Intimate," an echo of the company's racy advertising aesthetic. Other shades on tap include "Topless," "Pantytime," "In the Red," "Jackoff Frost" and "Sexual Harassment in Violation of the Fair Employment and Housing Act Govt. Code 12940(k) Shimmer."

Music makers: Boots cosmetics line 17 commissions up-and-coming musicians to write and perform songs that align with the ethos of 17 products. As in, "You Might Get Stuck on Me" for their magnetic nail polish.

"Let women of sixty use 'beautifiers,' if they think they need them. But you, who are young, pretty, and have a complexion like a rose-leaf—you should avoid such things as you would a pestilence."

99% marketing: For its 132nd birthday, Ivory soap is unrolling a new ad campaign, which hinges upon it being A) nongendered, and B) soap. Revolución!

Baby fangs: Intellectually I should be against about the practice of yaeba, in which dentists in Japan artificially enlarge their lady patients' incisors to create a childlike appearance. But as someone who is genetically blessed with noticeably sharp and semi-crooked incisors, I'm basically all, I am gonna be huge in Japan.

Vaniqua'd: The active ingredient in Vaniqua—you know, the drug you're supposed to take if you have an unladylike amount of facial hair—is also an effective treatment for African sleeping sickness. Of course, the places where African sleeping sickness strikes can't afford to buy it. But hey, our upper lip is so smooth! (via Fit and Feminist)

La Giaconda: The Mona Lisa, retouched.

Beauty survey: Allure's massive beauty survey reveals that 93% of American women think the pressure to look young is greater than ever before. Am I a spoilsport by pointing out that every person who answered that question is also older than they ever were before? (Of course, the "hottest age" for women according to men surveyed is now 28, compared with 31 in 1991, so there may be something to it.) Other findings: Black women are three times as likely as white women to self-report as hot, and everyone hates their belly.

Gay old time: Jenelle Hutcherson will be the first openly lesbian contestant of Miss Long Beach—and she's going to wear a royal purple tux for the eveningwear competition. The director of the pageant encouraged her to sign up, and Hutcherson has been vocal about how she's reflecting the long tradition of diversity and acceptance in Long Beach. (Thanks to Caitlin for the tipoff!)

Miss World: In more urgent beauty pageant news, British women protest Miss World, and somehow the reporter neglects to make a crack about bra burning.

The freshman 2.5: Virginia debunks the "freshman 15," and then Jezebel reveals that the whole thing was an invention of Seventeen magazine, along with the notion that every single New Kid on the Block was supposed to be cute.

Ballerina body: Darlene at Hourglassy examines the push-pull between embracing and dressing large breasts (which she does beautifully with her button-front shirts designed for busty women) and her love of ballet. "By the end of the performance I wasn’t paying attention to anything but the movements. There was nothing to distract me from the dancers’ grace and athleticism. Would I have been distracted by large breasts on one of the dancers? Definitely."

(Still taken from SOMArts promotional video)

Subject/object: Prompted by this intriguing Man as Object exhibition in San Francisco, Hugo Schwyzer looks at the possibilities for desiring male imperfection. He's the expert here, both because of his research and his male-ness, but I can't help but wonder how much men have internalized the notion of male perfection. I have zero doubt that the focus on the body beautiful has impacted men, and certainly the tropes of masculinity are a reasonable parallel to the tropes of femininity. But there's always been more room—literal and metaphorical—for men of all varieties to be considered sex symbols. Everyone gawked when Julia Roberts paired up with Lyle Lovett, but even then there was talk of how he had "a certain quality." Save someone like Tilda Swinton—who, while odd-looking, isn't un-pretty either—when have we ever spoken of women in that way?

Am I the only one who thinks gigolo should be pronounced like it's spelled?: Tits and Sass has been looking for voices of male escorts, and lo and behold, Vin Armani to the rescue!

"Did my son inherit my eating disorder?": There's been some talk about how a mother with food issues can transfer that to her daughters—but Pauline wonders if she's passed down her eating disorder to her son. A potent reminder that boys internalize ED factors as well.

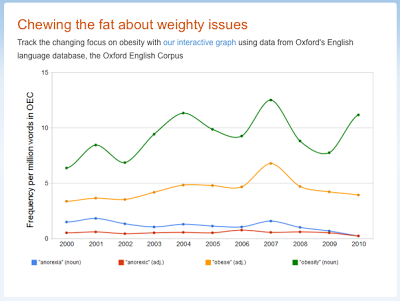

What you can't tell by looking: And along those same lines, Tori at Anytime Yoga reminds us shortly and sweetly that eating disorders of all forms come in a variety of sizes. This is enormously important: I'm certain that there are many women with eating disorders who don't recognize it because they don't think they fit the profile.

In/visible: Always glad to see celebrities acknowledge that looking they way they look actually takes work, à la Jessica Biel here: "My signature style is a 'no-make-up make-up' look, which is much harder than people think." Well, probably not most women who do no-makeup makeup, but whatevs.

Touchdown: This BellaSugar slideshow of creative makeup and hairstyle from NFL fans in homage to their favorite teams is a delight. I could care less about football itself (I finally understand "downs," I think) but I think it's awesome that these people are showing that there are plenty of ways to be a football fan, including girly-girl stuff like makeup. (IMHO, football fans could use a PR boost right about now. Seriously, Penn State? Rioting? You do realize your coach failed to protect multiple children from sexual assault, right?)

Face wash 101: Also from BellaSugar: There were college courses on grooming in the 1940s?!

She walks in beauty like the night: A goth ode to black lipstick, from XOJane.com.

Muppets take Sephora: Afrobella gives a rundown of the spate of Muppet makeup. Turns out Miss Piggy isn't the first Muppet to go glam.

Love handle: The usual story is that we gain weight when we're stressed or unhappy because we're eating junk food to smother our sorrows—but Sally asks about "happy body changes," like when you gain weight within a new relationship.

Locks of love: Courtney at Those Graces on how long hair can be just as self-defining as short.

_____________________________________

*Numerology field day! More significantly, Veterans' Day. Please take a moment to thank or at least think of the veterans in your life—you don't have to support the war to support soldiers. It's also a good time to remember that not all veterans who return alive return well: The Huffington Post collection "Beyond the Battlefield" is a reminder of this, particularly the story of Marine widow Karie Fugett, who also writes compellingly at Being the Wife of a Wounded Marine of caring for her husband after his return from Iraq; he later died from a drug overdose.

While most combat roles are still barred to women, there are plenty of female veterans—combat, support, and medical staff alike. Click here to listen to a collection of interviews from female veterans of recent wars, including Staff Sergeant Jamie Rogers, who, in When Janey Comes Marching Home, gives us this reminder of the healing potential of the beauty industry: "I went [to the bazaar near Camp Liberty in Baghdad] often to get my hair cut. They had a barber shop and then they had a beauty salon. It was nice to go in and it was a female atmosphere. It was all girls. You could put your hair down, instead of having it in a bun all the time, get it washed. It was just something to escape for a while, get away from everything. And it was nice to interact, and the girls were always dressed nice and always very complimentary: 'You have such beautiful...' and I don't know if it was BS, but it felt good that day. That was a good escape."