When people ask me what I like to read, the first word out of my mouth is usually "nonfiction." My reasoning is simple: I like to read about what I like to write about, namely physical appearance and its intersection in women's lives. And the open-minded part of me cringes to admit this, but: I've tended to believe that fiction isn't the place for this. Sure, the occasional

piece might illuminate an aspect of women's stories, but on the whole, I'll stick with my nonfiction shelf—Wolf, Berger, Sontag, Etcoff, Steinem, and so on.

Had

Fractals,

Joanna Walsh's new collection of short stories from

3:AM Publishing, been published earlier than this October, my answer would have changed earlier as well. I'd mistakenly conflated

nonfiction with

truth, entirely forgetting that fiction allows us to tell a different sort of truth—particularly about internal experiences. Like how, as with Walsh's characters, we might keep ourselves groomed for an absent beloved we privately know will never arrive, or how we make silent bargains about our looks ("The man with the steak looks at my legs which gives me permission to look at the message he is typing into his mobile phone. I cannot see it as the glass reflects. I feel cheated."). I knew from my first encounter with Walsh's work—

an illustrated look at five female authors, and how their self-presentation plays into their reputation—that she was as intrigued by beauty as I was.

Fractals expands her thoughts on the matter, with a direct focus on how the rituals of womanhood affect not only how we're seen by the world, but how we see ourselves. Her characters are keenly—sometimes painfully—aware of how they present themselves visually, treating clothing as a talisman, as a reaction to life events, as a confirmation of who they think they want to be.

When I asked the U.K.-based Walsh how she tailors her own choice of clothing to her state of mind, she had this to say: "I haven't, so far, done any sort of public appearance (and I love doing readings) in a skirt or dress.

I feel more authoritative in androgynous clothes, which I know is not a very worthy feeling as it's got to be to do with kowtowing to the way I intuit 'feminine' and 'masculine'-looking people are perceived. But there's also an element (another anxiety) of making writing look like 'proper' work—manual work even. I occasionally wear a boiler suit to read, and I always feel very comfortable. I think of the Surrealists in their suits: artists and writers who refused to look 'bohemian', who refused to make the distinction between what they did and less 'artistic' jobs. So when working at home I rarely stay in pyjamas. However I

do own, and wear, a variety of pretty dresses..."

Enjoy "Fin de Collection," one of the stories from

Fractals, below—and

leave a comment on this entry to enter to win a copy of the collection from 3:AM. Winner will be chosen by random number generator; leave a comment by 11:59 p.m. EST November 12 to enter.

* * *

A friend told me to buy a red dress in Paris because I am leaving my husband.

The right teller can make any tale, the right dresser can make any dress look good. Listen to me carefully: I am not the right teller.

Even to be static in Saint Germain requires money. The white stone hotels charge so much a night just to stay still, just so as not to loose their moorings and roll down their slips into the Seine. So much is displayed in the windows in Saint Germain: so little bought and sold. No transactions are proposed that are not so weighty for buyer and seller as to be life-changing. But, for those who can afford them, they no longer seem to matter.

The women of the quarter are all over 40. They smell of new shoe leather. I walk the streets with them, licking the windows. Are we only funning that we could be what is on display? It is impossible to see what kind of women could inhabit those dresses but some do, some must. Nobody here is wearing them.

Amongst the women I am arrogant. I retain my figure without formal exercise. I retain my position as a wounded woman like something in stone, infinitely moving and just a little silly. In order to retain my position I must be wounded constantly. This is painful, but it is a position I have become used to.

We turn into Le Bon Marché department store, the women and I, Vogue heavy in our shoulder bags.

There is nothing like Le Bon Marché if you are rich and beautiful. But if you are not rich or beautiful, it doesn’t matter. The store has its own rules. It is divided into departments: fashion, food, home. It is possible to find yourself in the wrong department but nothing bad can happen here and, although you may be able to afford nothing, it costs nothing to look.

Le Bon Marché is always the same and always different, like those postcards where the Eiffel Tower is shown a hundred ways: in the sun, in fog, in sunsets, in snow. It may look different in Spring or Autumn, at Christmas or Easter, but the experience it delivers is always the same.

There are no postcards of the Eiffel Tower in the rain but it does rain in Paris, even in August. And when it rains, you can shelter in Le Bon Marché, running between the two ground-floor sections with one of its large orange paper bags suspended over your head (too short a dash to open an umbrella).

Inside is perpetual summer. Customers complaining of being too hot are forced to take off their coats beneath the stencils of artificial flowers that bloom across midwinter walls. The orange paper carrier bags are not made for real weather, either. Once wet their dye leaks onto hair, coats, and leaves orange stains on pale carpets, clothes, floorboards...

Fin de collection d’éte. In Le Bon Marché it is already Autumn. The new collections are in order. They do not privilege experience. With time they will deteriorate, unbalance, as each key piece sells out, leaving a skeleton leaf of basics, black and grey. One can commit too early of course. A key piece bought nearly in style will merely foreshadow the version available when the style is at its height.

In 35 degree heat, we bury our faces in wool and corduroy. We long for frost, we who have waited so long for summer. To change clothes is to take a plunge, to holiday. Who cares if we cannot afford to leave Paris. In the passerelle, the walkway between the store’s two buildings, a tape-loop breeze, the sound of water, photographs of a beach...

There is something about my face in the mirrors that catch it. Even at a distance it will never be right again, not even to a casual glance. Beauty: it’s the upkeep that costs, that’s what Balzac said, not the initial investment.

Je peux vous aider?

The salesgirl asks the fat woman with angel’s wings tattooed across her back. She mouths, Non, and walks, with her thin companion, into the passarelle, suspended.

The first effect of abroad is strangeness. It makes me strange to myself. I experience a transfer, a transparency. I do not look like these women. I want to project these women’s looks onto mine and with them all the history that has made these women look like themselves and not like me.

From time to time I change my mind and sell my clothes. I sell the striped ones and buy spotted ones. Then I sell the spotted ones and buy plaid. Does it get me any closer? At the checkout, the thin girl in her checked jacket looks more appropriate than me, though her clothes are cheaper. This makes me angry. How did her look slip by me? I was always too young. And now I am too old.

I cannot forgive them. I forgive only the beauties of past eras: the pasty flappers, the pointed New Look-ers. They are no longer beautiful. They cannot harm me now. These two are not even the beautiful people. It’s more that they’re so much less unbeautiful than everyone else. Please remember, we are in Le Bon Marché. Plunge into the metro if you want to encounter the underground of the norm.

Even your other women seemed tame until I saw them through your eyes, until I saw the attention you paid them. I no longer know the value of anything. And if you do not see me, I am nothing. From the outside I look together. I forget that I am really no worse than anyone else. But how can I go on with nobody, with no reflection? And how, and when, and where can I be inflamed by your glance? I can’t be friends with your friends. I can’t go to dinner with you, don’t even want to.

But why does the fat woman always travel with the thin woman? Why the one less beautiful with one more beautiful? Why do there have to two women, one always better than the other?

Je peux vous aider?

Non. There are no red dresses in Le Bon Marché. It isn’t the dress: it’s the woman in the dress. (Chanel. Or Yves Saint Laurent.) Parisiennes wear grey, summer and winter: they provide their own colour. I have learned to imitate them. Elegance is refusal. (Chanel. Or YSL. Or someone.) To leave empty-handed is a triumph.

In any case come December the first wisps of lace and chiffon will appear and with them bottomless skies reflected blue in mirror swimming pools.

To other people, perhaps, I still look fresh: to people who have not yet seen this dress, these shoes, but to myself, to you, I can never re-present the glamour of a first glance.

To appear for the first time is magnificent.

______________________________________

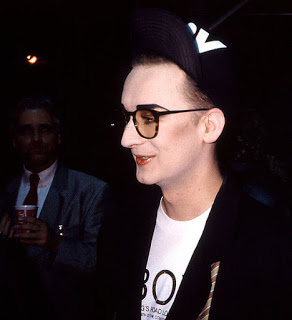

Joanna Walsh is a writer, illustrator, and artist. She draws and writes for The Guardian, The Times, Metro, The Idler, FiveDials, 3:AM, Berfrois.com, Necessaryfiction.com, and The White Review, amongst others. She has created large-scale artworks for the Tate Modern and The Wellcome Institute and has developed immersive theatre/games events in collaboration with Hide and Seek and Coney Agencies, as well as games she runs herself. You can read her blog at Badaude, and follow her on Twitter here.

Photo: Wayne Thomas