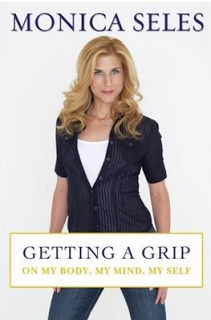

“I feel obligated to educate anyone that doesn’t wear a uniform about what military service is like,” says Miyoko Hikiji, a nine-year veteran of the U.S. Army whose career began when she joined the Iowa Army National Guard in college, eventually leading her to serve with the 2133rd Transportation Company during Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003. Her recently published book, All I Could Be: My Story as a Woman Warrior in Iraq (History Publishing Company, 2013), goes a good ways toward that obligation. And when I found out that the soldier-turned-author also began modeling upon retiring from the military, well, how could I not want to interview her? Beauty is hardly the most crucial aspect of a soldier’s life, but it’s an area unique to female soldiers, who make up 15.7% of active Army members—and who, in January, had all military occupational specialties opened to them, including combat units previously closed to women. Hikiji and I talked war paint, maintaining a sense of identity in extraordinary circumstances, and Hello Kitty pajamas. In her own words:

On-Duty Beauty

Military rules about appearance are pretty strict. Your hair has to be tied back in a way that doesn’t interfere with your headgear and that is above the collar of your jacket. That pretty much leaves it in a tight little bun at the nape of your neck. Once you get your two-minute shower and get out soaking wet, you just braid it together and it stays that way all day. After a mission or training, most of the women with longer hair wore their hair down, because having it in a bun under a helmet is really uncomfortable. In Iraq I might have had eyeshadow, from training and preparation before we actually got to Iraq. When we’d be in civilian clothes I’d have a little makeup for chilling out. But once I was actually in Iraq, I was more focused on sunscreen, moisturizer, vitamins. I just wanted to be healthy. And I had a stick of concealer. I wore that for some of my scars—there were a lot of sand fleas, and I had bites all over my body.

I couldn’t really approach trying to cover them well and look nice when I was there; I just needed to be clean. When I came home I did microdermabrasion for months to get rid of the scars. And I couldn’t wait to get regular haircuts. I also got my teeth whitened—we took daily medicine to protect against infection and malaria and stuff like that, but it makes your teeth turn yellow.

In Kuwait I think we got a shower once every three days. We took a lot of baby wipe baths. Those lists that say, Send this to the troops—baby wipes are always on there. I did try to get my hair washed as often as I could. A lot of women would put baby powder on their hair and brush it out, to absorb the oil and the dirt. I’d just dump canned water over my head if that was the best I could do. If I was up by the Euphrates I would shave in the river if I had a chance, but that was something you didn’t get to do very often.

On War Paint

The idea of makeup as war paint is interesting. Actual “war paint”—camouflage paint—is like a little eyeshadow pack, so in camouflage class or in the field, you’d have a woodland one that has brown, two shades of green, and a black. You’d put the darkest colors on the highlighted parts of your face so they’re subdued, and then you kind of stripe the rest across your face. It’s extremely thick, almost like clay; you wear it and you sweat in it and it’s just there. It’s kind of miserable! But if you look at yourself in the mirror after doing these exercises with the camouflage paint on, it’s hard to look at yourself the same way. There really is something to putting on the uniform or the camouflage, or just the effect you have when you’re holding a loaded weapon. All that contributes to your behavior. So I definitely feel different when I wake up and put my regular makeup on.

I approach the world differently, and the world treats me differently. What is it that we’re fighting? That’s hard to say. On some levels, I feel like when I wear makeup I’m buying into the whole thing of what a man tells me looks pretty, or that I’m kind of giving up part of my natural self. But then I justify it by saying, Well, it works, or Well, I’m getting paid to do that right now, with modeling. There is a lot of conflict there. It’s sort of a war on self, sort of a war on womanhood.

On Modeling

There was a tactical gear company filming some commercials at Camp Dodge, where I trained. They were going to have the actors go through an obstacle course I’d been through, doing everything at the grounds that I’d been training at for years. At the audition they said, “We’d like for you to have weapons experience, because we’re gonna shoot some blanks out of M-16s.” I thought, There’s no way I’m not gonna get this part. And then I didn’t. They picked people who were bigger, probably a little gruffer. People who looked the stereotype of what you think a soldier looks like.

To be fair, I don’t know all their criteria, so it’s easy for me to say they thought I was too pretty, too feminine. I don’t know that. But I do know that people who were picked for that modeling job didn’t have more experience than I did. Certainly none of them had weapons experience like I did. I think that they just didn’t believe that I fit the bill of looking like a soldier.

My experience in the military couldn’t have been anything but a benefit to anything I did in the future. Whenever I have a modeling job I always show up on time or early. I always have everything I’m supposed to have—not only do I print it out, but I check it just like a battle checklist. I look at every project like a mission. When I get there, I always have enough of whatever is needed to take care of somebody else who’s not prepared, which would be a squad leader’s position. I’m used to all that, and the people I work for are usually kind of surprised. In the middle of a job, if something happens, I’m okay with cleaning it up, whereas maybe other models or actresses might feel like that isn’t what they’re being paid to do, or that it’s a little below them. But you do so many crappy jobs in the military. You burn human poop! You have a bar for what you’re willing to do, and mine is all the way at the bottom. Things just don’t bother me or gross me out.

My great-grandmother was born in Japan, and my grandmother and my father were born and raised in Kauai. Being part Japanese adds another element to modeling, especially in Iowa, where the population for minorities is so low. There’s a Colombian model and a Laotian model here, so it’s kind of a joke among us when the call goes out for these jobs—which minority are they going to pick? And for scenes with couples, there are people they’ll always pair together and people they never will. Last commercial I did, I was paired with a guy who was just Mexican enough. They’ll pair me with a black man, but they don’t pair a black man and a white woman together—I’ve never seen that for a commercial shoot. I’m half Czech also, but they use me for the Asian slot, and then they try to Asian me up. They’ll tell the makeup artist, Can you make her look just a little more Asian? It’s like, I know we’re filling the Asian slot, but we’ve got to make sure it actually looks like she is.

All I Could Be: My Story as a Woman Warrior in Iraq, Miyoko Hikiji, History Publishing Company, 2013; available in Barnes & Noble bookstores and online

On Uniformity

One thing I thought was funny was pajamas. All the guys slept in their brown T-shirt or just their boxer shorts, because it’s not like guys wear pajamas; that wouldn’t be acceptable in that world. But all the women had pajamas! And it was always something funny, like Rainbow Brite or Hello Kitty or something. At that point in the night we just wanted to be girls. On active duty, if it was a three-day weekend, you could wear civilian clothes to the final formation before being cut loose for the weekend. The guys looked basically the same—they’d wear jeans and a T-shirt, but they wouldn’t really look different. But if I showed up in a dress, they just couldn’t believe it! Women can have a lot more faces than men can have—men can’t change their appearance the same way women can, especially in a situation where they all have short hair. But a woman really does look a lot different in her civilian clothes, and I was one of only a few women in a unit that had just opened its ranks to women when I first joined in ’95. So the guys kind of looked at me like, Is that really the same person? I think it confronted them a bit about who exactly I was.

There was also a conflict around presenting a different face to myself. When I was wearing a uniform I felt a little tougher, like I was blending in better with the guys. I didn’t really look like them, but at least I looked more like them than when I was wearing civilian clothes. And when I’d be in a situation where I’d look nicer, sometimes I wouldn’t even tell people that I was in the army—sometimes I would, if I was in a mood to challenge stereotypes. But the two identities don’t seem to fit well because of the stereotypes we have—tough people are supposed to look gritty and dirty and cut-up with tattoos. And then people who are attractive—well, that’s not supposed to be tough at all. The movie G.I. Jane was a terrible depiction of that. Even though it tried to be a girl power movie, in order for Demi Moore to be one of the guys, she had to look like a guy. She had to shave her head because that was how she could reach that level.

I think that’s a real issue in the military—and in our society—about beauty and gender stereotypes, that pretty can’t be tough. It became kind of a side mission of mine. Whenever anyone entered the room and said, “Hey guys,” I’d say, “Wait, what about me?” They’d say, “Oh, you know we mean you too.” Well, no, not really, because I’m not a guy. I wanted to point out that I’m doing the same job, but I’m not really one of you. That’s okay, we’re different—as far as the mission is concerned we’re basically equal, but we do do things differently. It’s not a bad thing!

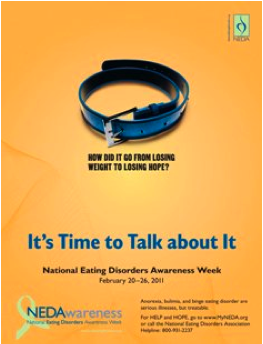

But let’s recognize who is it that the women are, because a lot of times I think we feel women have to be assimilated into manhood as a promotion into soldierhood, because we don’t think about soldiers as being women. We just think about them as being men. In the beginning I was so eager to assimilate and be accepted. I was okay with losing a bit of identity because I was becoming this new and different and better person—I was going to be a soldier and that was more important to me at the time than preserving some sort of identity as a woman. But by the time it got to the end of my military career I looked at things differently. In Iraq, on laundry day there would be clothes hanging out on lines that people would just string up wherever you could find a space, and some women had Victoria’s Secret underwear and lacy bras. At first I thought, What in the world? I don’t need a wedgie in the middle of a mission. But by the end it made sense to me, because we lost everything while we were there.

We lost our privacy; we lost a lot of our dignity. We were asked to do things that people probably shouldn’t be asked to do. So if you can hang onto something that is meaningful to you—whether that represents your femininity or your strength or your individuality, which we lost also—then what difference does it really make? It means something to them. Everybody has to find their thing to help get them through. You know, men don’t have to drop a lot of their stuff when they get deployed, but there’s a lot of pressure on women to change, to fill those soldiers’ shoes. The military uniform takes away women’s body shape; you don’t really have hips anymore, or a bust. It makes you realize how much just being a woman and being seen as a woman, let alone being attractive, plays into your life, because suddenly all that’s kind of gone.