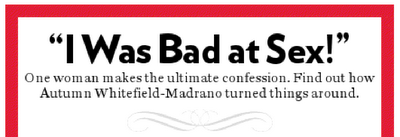

This isn’t about an abusive relationship. This is about what happened next.

I decided to leave my boyfriend not because he had ever hurt me, but because I was turning 30. I mean, he

had hurt me, but by the time I left him, it had been four years since he’d touched me with intent to harm. Our first year together was violent; eventually he was arrested for domestic assault, and he was one of the small percentage of men who go through a batterer intervention program and never harm their partner again. For the years that followed his arrest, I stayed with him because I needed to prove to myself that there was a reason I’d stayed in the first place. The relationship was never a good one, but by its end, it was tolerable. That is why I left.

More directly, I left because one day at age 29 as I was rising from a nap I literally heard a voice in my head say, “If you do not leave now, you will spend the rest of your life like this,” and while I had thought such things plenty of times, I had never

heard it, never

heard it with such finality and stark potency, and it was too true to be ignored. I spent a few weeks figuring out how I would do it in a way that would cause the least damage, and then I did it, and that is where this story begins.

* * *

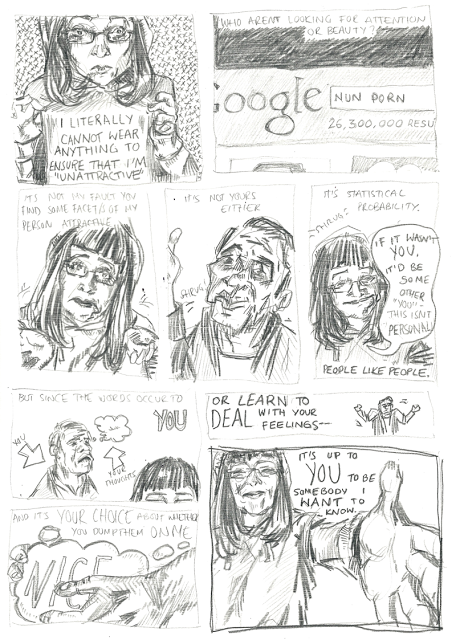

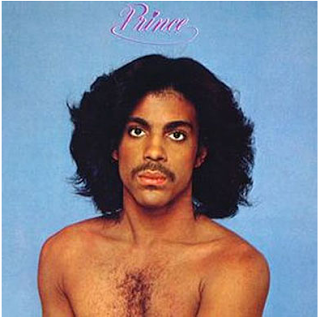

A few things happened around the time I decided to leave. First, I lost a lot of weight. Once I’d done that, I bought new clothes, clothes that were different from my normal jeans-and-hoodies gear that I had chosen because I didn’t like to wear anything that was designed to be looked at. I started wearing skirts and cute little dresses with cute little heels. I got a shorter, more daring haircut; with my diminished size I began to look nearly gamine. The increase in exercise made my skin glow. I discovered liquid eyeliner. “When did you become such a babe?” a coworker asked. “You’ve been an undercover hottie all this time,” said another. I would remember this as I’d go to the gym or plop down sums of money on clothes that had seemed unimaginable to me only months before.

You might think, as I did at the time, that my self-guided makeover was about rediscovering my self-worth. It was partly that, yes: When your “emergency contact” is the same person at whose hands you have suffered an emergency, your sense of self-worth isn’t exactly at its healthiest. It wasn’t difficult to see that my physical changes were announcing my renewal to the world.

But it wasn’t just change that drove me, nor even the satisfaction of looking good as I began to create a better life. This era wasn’t the first time that I’d felt pretty or had been called such. It was, however, the first time I felt like I “passed”—passed as someone who was blandly, conventionally, unremarkably pretty; passed as pretty without anyone having to look twice to make sure it was true.

When you’re in an abusive relationship, or at least when you are

me in an abusive relationship, you don’t recognize how standard your story is. You think that you’re special. That

he’s special, that he needs your help and that’s why you can’t leave; that you’re special for recognizing what a great gift you’ve been given, despite its dubious disguise. I never believed the cliche of “he hits me because he loves me,” but I came close:

I stayed because I truly believed I alone was special enough to see through the abuse to see him, and us, for what was really there. It was an isolating belief—another characteristic of abuse, one I didn’t recognize at the time—but moreover, it was a combustible mixture of arrogance and piss-poor self-esteem, and one that made me feel unqualified to ever play the role of Just Another Person.

Upon exiting the relationship I’d finally recognized as anything but special, I wanted nothing more than to be unremarkable.

Striving to be conventionally pretty was my way of re-entering the world of, well, convention. It was no accident that the first post-breakup date I accepted was with the most conventional man I’ve ever gone out with: a hockey-loving lawyer with a tribal armband tattoo who used the term “bro” without irony. It wasn’t that I thought his was a world I ultimately wanted to inhabit; it was that I needed to prove that the “special” men weren’t the only ones who would see me and want to see more. So I put on a pretty little dress with pretty little lingerie underneath, and I let him buy me dinner. I showed little of my inner self to him—I wasn’t ready for that, and I knew he wasn’t the one to show myself to anyway. But eagerly, and with every convention a pretty girl might use on a good-looking bro, I showed him the rest.

Beauty can be a tool. It can be a tool we use to tell the world we want to be a part of what’s going on; manipulating our appearance can be a tool we use to trumpet a part of ourselves that might otherwise go unseen.

Beauty can be a way of participating.

To be clear, I don’t think adhering to the conventions of beauty is the way most of us become our most beautiful. Our spark and passion will forever trump our perfectly whitened smiles or disciplined waistlines. But for me, beauty became a tool to let myself begin to believe that I was worth being seen. When I was recovering from a life of apprehension—after years of longing for even a single day when the first thought that entered my mind in the morning would have nothing to do with him, after years of exhausting my every resource to try to convince my family and friends and boss and above all myself that

I could handle it—the stream of assurance I got from looking pretty in an everyday, pedestrian, stock-photo, conventional sort of way was a lifeline. I let the slow drip of looking unremarkably pretty sustain me while I began the real work of rebuilding.

Beauty—or rather, giving myself the tools of banal, run-of-the-mill, utterly ordinary prettiness—allowed me to reconstruct a part of myself that had gone mute for years. And then, I constructed another, and another, and another.

* * *

During the time I was dating the bro, I also became involved with a man with whom I formed a poor romantic match but, as it turns out, an excellent friendship. We stayed in touch after we stopped dating, but I hadn’t seen him again until last year, when I happened to be visiting the city he now calls home. I was backpacking, and the clothes I wore reflected that—jeans, layered T-shirts, a grungy hoodie, worn not out of a desire to avoid anyone’s gaze but for comfort and practicality.

I mentioned what a relief it was to not be wearing high heels. He eyed me evenly. “The little dresses you wore when we were seeing each other—they weren’t you,” he said. He sensed my recoil and amended: “You pulled them off, no worries. You looked good. But even though I hadn’t ever seen you wear anything else, I could tell it wasn’t...

you. It wasn’t the you I knew.” In part, he was right. The cute little dresses, the high heels, the smart haircut: In embracing that part of myself to the exclusion of all other styles, I was still reacting to a desperately unhappy time of my life. I wore red nail polish because my ex hated it; I wore heels because he liked me so much in sneakers. I wore dresses because, for the first time in years, I truly wanted to be seen.

It had been fine for me to embrace a conventionally feminine look to alter my baseline of how I wanted to present myself to the world. And I didn’t need that baseline any longer.

Yet what stands out to me now about that exchange isn’t the message, but his words,

It wasn’t the you I knew. Abuse had swallowed me to the point where I could no longer detect my own identity—but he, and other people I was wise enough to trust, could. We form our self-image not only from ourselves, but from those around us. When you are in the fog of abuse, the chaos and torment that occupies the abuser’s inner life becomes your own. When you leave, that fog is replaced with what and who is around you: the man who said

It wasn’t the you I knew; the friend who raised her glass “to the beginning of you” when I told her I’d left; the running partner who, years later, would become a partner in other ways as well. Even the tattooed-armband “bro” was an imprint of my desire to be utterly cliché for a while before turning my head toward what might

actually make me special. Each gave me what beauty did—a sense of normality. But they also took me beyond the limits of what conventional prettiness could ever do.

They reflected back not only what I knew of myself, but what they knew of me. They were my mirror.

I don’t recommend that any of us form our mirror entirely from others; that’s part of what lands some of us in an abusive relationship to begin with. But when you are beginning to rebuild a bombed-out identity, you need something beside you other than just your naked soul. The people around me were part of that. Beauty was another.

The mirror of plebian prettiness is a precarious one. It’s not built for the long haul, and it is easily shattered. There are a million ways my unintentional strategy could have been disastrous. But people who are recovering from difficult situations are often told to draw from their “inner strength”—good advice that forgets that sometimes, every gram of inner strength is going toward just holding yourself together.

And with abuse, which is known for its powers of erasing the victim’s identity, the concept of “inner strength” is particularly questionable: You can’t draw from inner strength when you feel like nothing is there. I needed to draw from outer strength; I needed a routine that would help me reconstruct. I eventually got to reconstructing the inside. But I needed the framework first.

Attention to one’s appearance cannot be the end point of becoming our richest selves. But for some—for me—it can be a beginning.

_________________________________________

October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month, and this post is part of the Domestic Violence Awareness Month blog roundup at Anytime Yoga. If you are in an abusive partnership—whether you’re being abused, abusing your partner, or both—tell someone. You can begin by clicking here or calling 800-799-SAFE.