Thirty-six!

I had a birthday over the weekend, and it’s the first birthday I’ve had where I’ve been remotely tempted to be coy about my age. I’d never understood why anyone, particularly a woman, would lie about their age. I’d heard

the classic story about Gloria Steinem quipping to a reporter upon being complimented for looking good for her age, “This is what 40 looks like. We’ve been lying for so long, who would know?” While I loved the story, her reasoning made such innate sense to me that I actually had a hard time grasping its actual importance. Why

wouldn’t you claim your age, especially if you’d taken care of your health and pride in your appearance? Why would you say you were younger and risk looking “okay” for, say, 35 but fantastic for 40? It’s not like lying about your age actually

makes you younger, after all; it just gives you something else to feel ashamed of.

I’m not ashamed of my age, to be clear; I’m 36 and wouldn’t go back to my twenties if you paid me in rainbows. Still: As of Sunday, I’ve felt the slightest twinge of hesitancy about saying my new age. I’d never lie about it, nor will I avoid the question, but for the first time I’m at the age where I understand the impulse to do so. It’s easy to dismiss such thoughts as vain twaddle at 28. It’s a hair harder as I inch toward 40.

When I turned 30, people around me took delight in saying, “Forty is the new 30,” the idea being that where our parents supposedly had all their shit together by 30, the perpetual adolescence we GenXers had carved out for ourselves meant we had a whole added decade in which to do so. The larger import of this statement is about things beyond the scope of this blog—the ways we’ve reconfigured work, family, geography, careers, the idea of success itself.

But there’s something else lurking in the idea of 40 being “the new 30,” and the phrase that keeps coming to mind is, We look younger than our parents.

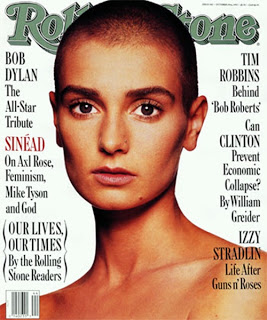

When I was in college, the hot new face belonged to an actress named Jennifer Aniston, who, at age 25, had found herself with the coveted Rachel haircut and a hit TV show. Thirteen years after my graduation, who do I see on magazine covers? A 43-year-old Jennifer Aniston. And a 39-year-old Gwyneth Paltrow, 36-year-old Kate Winslet, 42-year-old Jennifer Lopez, 42-year-old Tina Fey, and 36-year-old Reese Witherspoon—all of whom were big or rapidly on their way there when they, and I, were in our 20s. Add to that the 38-year-old Elizabeth Banks, 33-year-old Rachel McAdams, 32-year-old Zooey Deschanel, 33-year-old Kate Hudson, 38-year-old Heidi Klum, 37-year-old Christina Hendricks, and 36-year-old Angelina Jolie, and it gets harder and harder to believe that Hollywood truly does fetishize youth as much as we say it does. Yes, there will always be the 18-year-old Dakotas and 22-year-old Kristens, but we’re in an unprecedented age of mature women being construed as alluring in the mainstream press.

Julianne Moore is 51. Want to know who else was 51? Rue McClanahan, when The Golden Girls first aired.

Part of this, I’d like to think, is a broadening definition of what beauty and allure actually

are, or at least an acknowledgement that women of a certain age have plenty of both, without anyone needing to fetishize the fact that they’re not 22. Anne Bancroft as Mrs. Robinson wasn’t only sexy for an older woman; she was just plain sexy. But there’s something else at play here:

People today look younger than people of the same age did a generation ago. Bancroft was 36 when she played Mrs. Robinson; Elizabeth Taylor a mere 34 as the aging Martha in

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. There are some technical reasons for this, starting with the greater knowledge base about aging we have available to us today. I may have spent my early years thinking of a tan as being “healthy,” but by the time I was a teenager the anti-sun brigade had thought to add “premature aging” alongside “skin cancer” on the list of reasons not to sunbathe. Same with not smoking, getting my omega-3s, and exercising—I may well have done these things regardless, but vanity is a pretty big motivator.

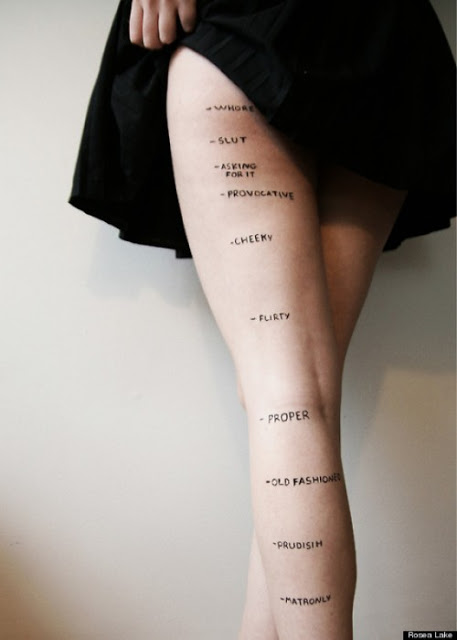

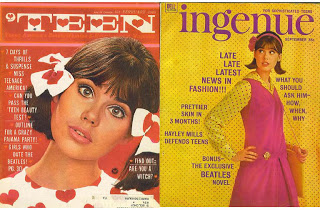

But the larger reasons are generational. With delayed marriage and childbearing—and, of course, the increased acceptance of saying no to either or both—comes a loosened idea of what adulthood itself really is, and its subdivisions are looser still. Age is just a number, but not because of what that Hallmark adage was designed to signify. It’s “just a number” because our conception of youth and aging is relative. There’s no such age as “old”; we collectively decide what “old” means, and within that we collectively decide upon the million variations of oldness: old enough to know better, too old to dress that way, old ladies. And because it’s relative, it’s always shifting, often without our consent. So the idea of a 40-year-old woman looked like one thing when I was 20, and another thing to me today at 36; what’s more, had I been 36 in 1982, a 40-year-old woman would probably have looked quite different than my conception of a 40-year-old woman today.

There is no Platonic Form of a thirtysomething woman; she must be relative and known to us through cues and sensations, not as some pure ideal of Thirtysomething Woman. Her template changes all the time: Not all that long ago, it wouldn’t be terribly unusual for a woman my age to not only be a mother but a grandmother. More recently, Jacqueline Kennedy’s pink suit and “helmet hair,” forever memorialized as the distraught First Lady, belonged to a 34-year-old woman; Meredith Baxter-Birney and Phylicia Rashad were 35 and 36, respectively, when

Family Ties and

The Cosby Show hit the air. It’s hardly a surprise that when I want to dress conspicuously adultlike, I often find myself reaching for clothes that recall another era, one with lines drawn more strictly for women versus girls—my tailored pink Jackie O-style sheath, my surprisingly demure leopard-print dress with a 1940s cut.

Of course, all those are things I can change—my clothing, my hair. My face, not so much. I’ve done many of the things that one is supposed to do for “anti-aging” (a nonsense term if there ever was one).

But so have most other 36-year-olds, so all that my efforts mean is that I look like other middle-class 36-year-old women in The Year Our Lord 2012, instead of looking like I might have as a middle-class 36-year-old in 1971. Collectively, we’ve decided that today’s 36 looks younger than our mothers did when we were in fifth grade, or even our surrogate TV mothers; instead, our 36 looks more like Kate Winslet, even if

we don’t. The things keeping us from looking like Kate Winslet are more along the lines of professional beauty treatments (and, um, genes), not some magical anti-aging potion. She looks her age. Most of us do.

All of this should make aging as we know it easier, and I suppose it does; I’m thankful that with some styling I can achieve the womanly look my grandmother had at my age, and thankful that I can shake loose of that consigned womanhood and wear some of the same things I might have in college without being considered inappropriate or, worse, pathetic. But underneath that is a cognitive dissonance with what I know up-close to be true: I am aging.

And while the reconfiguration of adulthood has liberated women like me from making semi-permanent life choices too early, it’s also easy to take from that liberation a free-floating fear or denial of aging and what aging actually looks like. There’s far less shame about the number of aging than there used to be—truly, the twinge of hesitancy I feel about saying I’m 36 is just that, a twinge. The greater fear is not saying I’m 36 but acknowledging that I’m 36—which, all told, isn’t seen as young but is hardly seen as old—and therefore have some of the signs of what we associate with actual, undeniable

oldness. Battle-won crow’s-feet are one thing. Knee wrinkles are quite another.

Aging “gracefully” is part of it, sure, but I’m less afraid of being seen as clinging to my fading youth than I am of being seen as having lost some sort of essence.

I’m less concerned about wrinkles than I am about things I’ve never had to think about before because they came naturally, like “tone” and “texture” and “radiance.” My most pronounced signs of aging haven’t been things that should rob me of that radiance; if anything, with age I have more energy, more vigor than I did when I was 24. I drink less, I sleep more, I exercise, I eat my greens. I’m far more nourished now in every way than I was then. And it shows—by nearly every conventional measure, I look better now than I did then.

But there it is, looming, unfair: No matter what I do, no matter how impeccable my self-care, there is a quality I had at 24 that I will never have again. I’ll happily take the tradeoff age has offered me—please, don’t miss that point—but it seems like a joke to me somehow

. I want the vitality my skin had at 24 not only because it looks “better” but because I feel like it’s rightfully mine. I feel more vital now; I feel more radiant. I hadn’t earned the look of vitality I had when I was 24, and I didn’t realize I hadn’t earned it; it was only when it began to slip away that I recognized that I’d been working on a pay-it-forward system that I hadn’t signed up for and couldn’t reneg on.

Thirty-six years young; today is the first day of the rest of our lives; it’s never too late to learn; you’re only as old as you feel. I will take these cheap sentiments over what people, particularly women, were faced with not so long ago, like marrying by 30 or resigning oneself to lifelong spinsterhood.

But an unintended side effect of age positivity is that we’re left with a clashing of ideals: If age is a state of mind, what do I do about the tangible ways in which that “state of mind” is showing up on my body? Without the other markers of adulthood, the ways I mark my age are internal, amorphous; I say I “feel” differently now than I did at 26, and I do, but I’d be hard-pressed to tell you exactly what that difference is. The biggest differences between my life now and my life when I was undisputably young are inarticulate—I still sleep on a futon, I still consider reheating Indian food “cooking,” I’ll still stay for one more drink—but there’s a definitive articulation of aging on my very form. The occasional thread of silver in my otherwise dark hair, the darkness beneath my eyes that never quite goes away, the way a day in the sun now makes me look haggard instead of bursting with California-kissed good health. It’s not that any one of these is so horrible but rather that it runs right up against my idea of myself as someone who’s aging but not, you know,

really aging. I’m not afraid of getting older; I’m not afraid of looking my age. But it was a lot easier to say that more loudly before I began to learn that “looking my age” would mean looking older in ways that so far had applied only to other people.

I am thankful beyond words that women before me have lived their lives so vibrantly as to make it clear that life doesn’t end at 30, or 35, or 55, or 75. Without them, the choices I’ve made in my life—to remain single, to freelance, to live alone in an urban space far away from family, to not have children, to be a lousy housekeeper—are largely viewed by those around me, and by myself, as

choices, not as some unfortunate set of circumstances that’s befallen me, the poor thing. But within all that positivity, I want to create a sliver of a space for mourning what has slipped away from me with age. Not so I can dwell on it, or long for its return, but so that I can honor this quality I had at a time in my life when I had every right to feel young, vibrant, and carefree but rarely consciously felt any of those things. In truth, what looked carefree at 24 was more often than not merely chaotic. I had no idea that despite that chaos, I carried with me a radiance that was mine simply by dint of being young. There is no way to say this without speaking in a cliche, so forgive me, but: I didn’t know what I had until it was gone.

My hope in allowing myself to mourn these small losses is that I’ll create room for the conscious recognition of what I have now, at a perfectly fine 36, that I haven’t yet recognized. What those gifts are, I’m not entirely sure, but I trust in their existence nonetheless. Perhaps the moment I stop doing so is the moment I really will grow old.