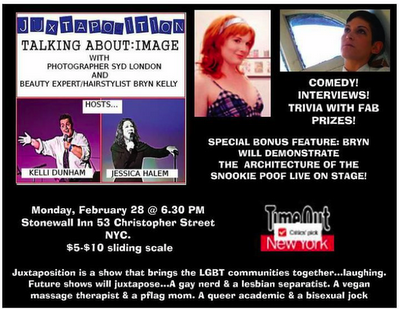

I love the mod look! The mod look does not love me (at left). But the coral lipstick at right is nice, oui?

A few months ago, I stumbled across a website that promised a “virtual makeover.” You’d upload a photo of yourself, then apply various “looks” with all manner of makeup colors and hairstyles; you could even “borrow” a celebrity’s entire look, pasting her makeup and hair onto your image.

I’d seen similar tools before, of course, but they were always comically bad—more along the lines of my friend Lindsay’s collection of horror-makeover images than anything you’d actually use to evaluate whether you’d look good in, say, coral lipstick. On a whim, though, I decided to give it a try, figuring that the technology must have changed since I’d last given them a whirl.

I was right. Though the results were obviously computerized, the tech had developed so that you could align your face more precisely in the application frame, meaning that lipstick actually landed on your lips instead of where the computer wanted your lips to be. More important, it was actually useful. I was surprised to find that I actually might look good in coral lipstick; I confirmed that, sadly, the mod look makes me look just wrong; I found a half-up, half-down hairstyle that looked great on me, and when I tried it out on terra firma, it was indeed flattering.

The site linked out to other sites that had features besides makeovers—you could digitally slim yourself down, or plump yourself up. You could get a breast lift, breast augmentation, or both, which served as a complement to the rhinoplasty and face-lift features on the makeover site.

Do I even need to tell you what happened? I went down the rabbit hole. Making adjustment after adjustment, I manipulated my face and body—just to see, of course. Learning what I’d look like with Gwen Stefani’s hair (absurd) led to seeing what I’d look like what Penelope Cruz’s hair (not bad), which led to me trying on dozens of brunette celebrity styles to see which might suit me best (Ginnifer Goodwin?). I plumped my body out 20 pounds to see if it would resemble how my body actually looked when I was 20 pounds heavier (it did), then trimmed myself down 10 pounds to see if it echoed my erstwhile 10-pounds-lighter frame (it didn’t, which didn’t stop me from going on to drop another 15 virtual pounds, because, hey, this is just a game, right?). I narrowed my nose, went up three cup sizes, ridded myself of my deep nasolabial folds, and alternated between digitally tanning and digitally “brightening” until I realized I was aiming for pretty much the skin tone I actually have. And then, a good two hours after I’d sat down to try on Gwen Stefani’s hair for a lark, I went to bed.

Now, there’s plenty to say here about the nature of that rabbit hole, and how it relates to self-esteem and dissatisfaction. (Is it any surprise that after inflating my breasts three cup sizes, clicking back to the photo of myself au naturel left me feeling deflated?) But in truth, after spending an evening creating a slimmer, bustier, better-made-up version of myself, the most pervasive feeling I had was not of self-abasement but of extraordinary fatigue. It was like I’d spent 12 hours proofreading a dissertation on, I don’t know, dirt, printed out in 7-point font. I felt the brain-drain not only of sitting in front of the computer for too long, but of doing crap I don’t actually feel like doing. Which is to say: I felt like I’d been working.

In fact, I sort of was working, even if I tricked myself into thinking I was doing it just for fun. It made me think of gamification, the use of game elements and digital gaming techniques in non-game situations. The idea, in part, is that by lending the benefits of gaming to more tedious tasks (like work), the tedium is lessened because it feels more like play. Perhaps you’ll be more likely to, say, complete online training courses if you earn “points” or “badges” for each segment you finish. It seems silly that something essentially imaginary would motivate people—but one peek at the popularity of programs like Foursquare that allow you to gamify your own life shows that it works. The term more broadly applies to any sort of game thinking that applies to non-game situations—like interactive features (that annoying Microsoft Word pop-up dude) and simulation (think 3-D modeling à la SimCity), though most of the critiques of gamification that I’ve read focus on its reward aspects.

The beauty apps I was mucking around with aren’t exactly examples of gamification, strictly speaking. There’s no points system for coming up with the “best” makeup look, and though sites like the one I used let you share your results on social media, there’s no competitive aspect—just you cycling alongside the beauty machine. (The exception I found was iSurgeon, which allows you to play surgeon on preprogrammed faces and earn points for each “successful enhancement” you make The site also encourages users to “perform plastic surgery on your family and friends right on your i-phone [sic],” but you can’t play a scored game on images you upload yourself.) Still, there are undeniable similarities between beauty apps and gamification: The swiftness with which you can wipe the slate clean, much like the neverending lives of video games; the toolkits you use to update your image, which are reminiscent of the palette of options presented to you in traditional video games when choosing whether your avatar is the spiky-haired kickass blonde or the artillery-laden robot, or whatever. (Can you tell I haven’t played a video game since Super Mario Brothers?) And most of all, it shares the addictive quality that kept me playing just one more game (one more hairstyle, 10 more pounds).

One of the more salient critiques of gamification has it that when employed in labor situations, it robs work of its true value, turning employees into soulless—but entertained!—lab rats. As Rob Horning put it in Jacobin magazine, “[Gamification] cheerfully assumes from the start that most of life’s tasks are inherently not worth doing...and contrives a motivational system that precludes the possibility of working from inspiration in accordance with some intrinsic personal desire, some self-conceived goal.” That is, gamification takes the drudgery out of work (at least, that’s its goal), which in turn makes work not something one does with a larger aim in mind—say, developing new skill sets, or learning how to focus and collaborate—but something one does in a Pavlovian way, hoping for the quick-hit reward of games.

Now, beauty apps aren’t employed in a structured labor situation, and as much rhetoric as I can spew about the beauty imperative, the fact is, for most women wearing makeup is a choice (that is, until you get fired for not wearing it). Certainly the types of beauty labor being mimicked in these games is optional; even if you feel you must wear concealer to leave the house, chances are you don’t need to try on 12 different lipstick shades too. But the very existence of apps designed to let us see the “rewards” of makeovers, or weight loss, or plastic surgery before we make the commitment any of them require indicates that to some degree, beauty is labor, and that we do appreciate incentives (free eyeshadow cybertrials, for example) that help make that labor more productive as well as more fun.

Yet it’s not until we contextualize beauty gamification within the larger frame of leisure games—which, at day’s end, is what makeover apps really are—that its true significance becomes clear. Horning again, this time on the video game Guitar Hero, which lets people pretend to play guitar as opposed to, you know, actually learn how to play guitar: “Novelty trumps sustained focus, whose rewards are not immediately felt and may never come at all. … [O]ur will to dilettantism develops momentum.” By giving pretend shortcuts to a skill that, in the real world, brings benefits that go beyond simply being able to bang out a decent “Leavin’ on a Jet Plane”—the joy of witnessing your own progress, the deeply felt satisfaction of mastery, the mental acuity that comes with learning a new “language”—Guitar Hero lets its players trade the long, slow process of learning a skill that you’re pursuing for the sheer fun of it for the dopamine hit of getting a high score. (Certainly I had more fun the two times I played Guitar Hero than I did the two times I held a guitar and awkwardly plucked out a few errant sounds—but it couldn’t compare to the afternoon I spent teaching myself to play “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” on ukelele.)

Enter beauty apps, which mimic acts that fall somewhere between leisure and labor. Now, I'm hardly worried that makeover sites are taking away our collective proficiency at eyeliner application, but the Guitar Hero argument applies anyway: I can spend half an hour in Sephora trying on various eyeshadows and lipsticks, but 30 minutes staring at my visage onscreen never really winds up feeling like leisure. Gamifying beauty combines gamified play’s curtailment of actual playfulness with gamified labor’s trivialization of actual work, forming a neither-nor zone robbed of both the joyful possibilities and the political significance of beauty work. It seeks to place beauty squarely in the “isn’t this fun?!” camp—and yes, it is fun to dabble in dozens of makeup looks without having to wash your face a zillion times, and it’s even fun (or especially fun) when the computerized results are ridiculous. As an activity in and of itself, it might be just fine.

But I wonder about the fallout of this reinforcement of the false notion that beauty work is strictly for play. It takes an act fraught with meaning—personal, cultural, political, gendered, class-oriented, expressive meaning—and turns it into something as consequence-free as Farmville. It renders beauty work as kittens’ play. And if beauty work were more fully recognized as the work it is, this wouldn’t be so bad; after all, Navy SEALs play Black Ops II, and civic engineers play SimCity. But beauty work largely isn’t recognized as work, isn’t recognized as (unpaid and costly) labor. Gamifying it, instead of actually lightening beauty’s labor load, only makes it appear evermore weightless. And unlike with the avatar of myself I created 30 pounds lighter—impossibly long-limbed and slim-hipped instead of the awkward, bony mess I’d likely be were I to actually lose that amount of body mass—weightlessness can’t be our goal.