False eyelash patent, 1911.

When I first heard about eyelash extensions, I threw it into the bin of Things I Would Never Do, along with Vajazzling and placenta facials. But when it came time to take my author photo—which will probably serve as the definitive photo of me, Internetwise, for quite possibly the rest of my life—laying on my back for an hour and a half to have my eyelashes individually extended seemed utterly reasonable. I wanted to look my best, but still wanted to look like me; emphasizing my eyes without wearing more dramatic makeup than I’d normally wear seemed like a good way to do that. It got me thinking about eyelashes—before getting eyelash extensions, I didn’t understand their importance. I don’t know how many surveys I’ve read that say that the number-one must-wear cosmetic women cite as essential is mascara. There was something there, and there has been for centuries.

- Latisse isn't the first eyelash-growth treatment out there. A partial list of treatments used throughout history to amp up eyelash growth: white wine, mint, lavender vinegar, glycerine, “fluid extract of jaborandi” (an herb that is now used to make prescription glaucoma medicine), red vaseline, a mixture of cornflower and chervil, quinine, almond oil, kohl (personally recommended by the prophet Mohammed), Spanish fly, and myrtle extract, most of which may be applied to the lashes with “a tiny camel’s-hair paint-brush.”

Nor are false eyelashes themselves particularly new. In 1911, an Ottawa woman filed the first patent for false eyelashes, which don’t look all that different from any strip of false eyelashes you might buy at a drugstore. (Her invention was cited in a toupee patent 43 years later, as well as numerous fake eyelash patents, so she was onto something.) D.W. Griffith is often credited with creating them in 1916, but while he did order a wigmaker to improvise a set of them while filming Intolerance, he wasn’t the first. Either way, the patent was decidedly less dramatic than the process described in a British newspaper in 1899, in which the eyelid was rubbed with cocaine, then threaded through with the client’s own hair.

People used to trim their eyelashes. The (erroneous) idea is from the same school of thought that sees parents shaving the heads of their daughters in an effort to make the hair grow back thicker and fuller. It doesn’t work that way, but magazines from the 1890s advise that lashes be “clipped with the scissors once in every five or six weeks, which is all the treatment they require to make them long and curved” (Current Literature: A Magazine of Contemporary Record, 1896). Not that people needed the advice, for “every mother knows that she has only to clip her baby’s eyelashes while it sleeps, and continue the process during its childhood, to render them as long and luxuriant as Circassian’s” (Ballou's Monthly Magazine, 1872). Other sources recommend eyelash trims, but for hygienic reasons; apparently 120 years ago people were getting all sorts of things wrapped up in their eyelashes. (Incidentally, this actually does happen with eyelash extensions. My lashes have been collecting detritus for weeks.)

We've been darkening our eyelashes for a while. You already know about ancient Egyptians and kohl, I’m guessing, which was used not just to rim the eyes but to tint their fringe. Women in parts of Asia used elderberry juice to color their lashes, as well as ashes from cork or incense. In Europe, India ink, gum arabic, and rosewater was recommended for a black hue; light-haired women were steered toward a mixture of red wine, salt, iron sulphate, a mass of oak chemically distorted by a wash, and French brandy. Basically, anything dark would do—frankincense, resin, plain old soot, mixed with something to make it stick. Once petroleum jelly came along, women started using it to give the appearance of thicker, glossier lashes, but the first commercial mascaras didn’t come about until the 1860s, with Maybelline mascara—a mixture of coal and petroleum jelly, and the first mascara in the States—being developed in 1913.

Like every other aspect of beauty, the quest for luxuriant lashes tells a deeper story. Because human history has such a rich history of attempting to lengthen and darken the lashes, it’s tempting to say that eyelashes are one of those things that has been valued for their beauty regardless of time or place. That’s not quite true, though: In medieval and early Renaissance Europe, lashes were considered unimportant, even ugly—they detracted from the forehead, that most beautiful of features (or so said the mores of the time). Women removed their lashes and brows to give the forehead its full due.

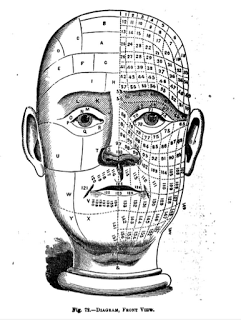

Still, luxe lashes aren’t a new invention of the beauty industry—women and men have indeed been thickening and darkening theirs since antiquity. But one period in particular stands out here. Many of the odd potions I’ve listed above—chervil for growth, red wine for color—were concocted in late 19th century Europe. Two other crazes were sweeping Europe at the same time: Orientalism, and physiognomy. Europeans became fascinated with the East, “othering” Asian society and rendering cultural practices impossibly exotic, the people full of mystery and secrets. The beauty rites of the East (including the “near East,” or the Caucauses, hence the mention of the eyelash trimming of the Carcassians) were a perfect example of this “mystery.” It intersected perfectly with physiognomy, the pseudoscience of reading people’s personalities through their faces. The “best-developed” fringe belonged to “the aesthetic and artistic classes”; long lashes could indicate shyness and timidity, or secretiveness, indicating that “their owner is too shy or too timid to be perfectly frank and outspoken.” Short lashes were for blunt, rude folks. They’re also “effective agents in love-making and coquetry,” which circles back to Orientalism. Women of the East were (and still are) seen as having an exotic sexuality; borrowing their eyelash hygiene was a way women of the West could borrow that appeal.

Eyelashes were particularly well-suited to physiognomy’s claims. Regardless of whether long lashes actually indicate a demure or coquettish demeanor, the fact is that if someone is peering at you through a thick fringe, you feel a sense of secretiveness: There’s a barrier there, one that separates eyes, those famous truth-tellers, from others who might discern how much truth is actually being told.All this is to say: I don’t regret getting eyelash extensions, even as the process of getting them made me feel incredibly high-maintenance. Which is appropriate: They are high-maintenance, quite literally, in that they do require maintenance. You can’t use oil-based makeup remover; you can’t let water stream down your face; you can’t sleep on your side (my solution here was to just sleep with my head on the pillow but my face off of it). No rubbing, no tugging, and you have to separate them every day with a mascara-less mascara wand, or else they’ll get all tangled up. (Finding a down feather wound between my false eyelashes from my pillow is probably my lifetime height of Luxury Problems—indeed, perhaps my lifetime height of luxury.)

I can’t say I’ll shell out for them again; I think of myself as far too practical to do so for any reason other than having a public photo taken. But I have an easy justification in case I do decide to re-up: Eyelash extensions, in some ways, are practical. I found myself not “needing” eye makeup on most days, only wearing it to punch things up a bit. Normally I wear eyeliner and mascara every day, largely because it makes me look more like I look in my mind’s eye. But it’s not like my mind’s eye sees myself wearing eyeliner; it sees me with my eyes more emphasized, more prominent in my facial composition than they actually are. Eyelash extensions did that. (It’s also difficult to apply eyeliner when you’re working around these 9-millimeter spider legs.) Even with the maintenance, it actually saved me time in the morning, this “natural” emphasis made possible by a completely fake creation. It didn’t save me money—eyelash extensions run a little more than $100 and last around a month—but for a short-term proposition it was worth it, and if I had more disposable income I might consider getting them more regularly. Barring that, I’ll just rub my eyelids with cocaine, thread a needle with my own hair, and hope for the best.