While in the midst of a twentysomething identity crisis, I took a spate of deliberately ugly photographs of myself. I’d been possessed by a sudden fear that not only was I a troglodyte, but that I’d been a troglodyte all along and just hadn’t known it, so I decided to face my fear by proving that I

could look like a troglodyte but wasn’t

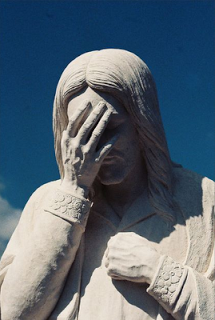

sentenced to it. The grand outcome was that I wound up with a bunch of troglodytic self-portraits. (I no longer believe I’m a troglodyte, for the record, but that’s a different post.) This was before digital cameras, and I’ve since lost the prints, but here’s a photograph that’s about on par with them:

Fun fact: The Troggs were originally called The Troglodytes!

It’s probably obvious why you haven’t seen this photograph before: It’s

terrible. But it’s hilarious to me, and I’m reasonably assured that it in no way captures my essence. (

Right?). That’s exactly why I can show it to you. What’s harder for me to put out there is this photograph:

It’s not like my eyes are half-closed or that I’m wearing a goofy expression, or that it highlights some flaw I’m self-conscious about (even if I do look a hair jowly). I dislike it not because it’s particularly unflattering

, but because I look timid and reluctant. It was a fleeting moment (I was at a joy-filled brunch but was

quite ready for my second bloody mary), but it captures my hesitant, mousy side

—a side I’d prefer not to exist at all. Yet it’s easier for me to show you the first photo

—taken at an unflattering angle, while I was making a weird face, halfway through a four-day backpacking excursion

—than it is to show you the second, in which I look perfectly fine and have done a certain amount of "beauty work" to look presentable.

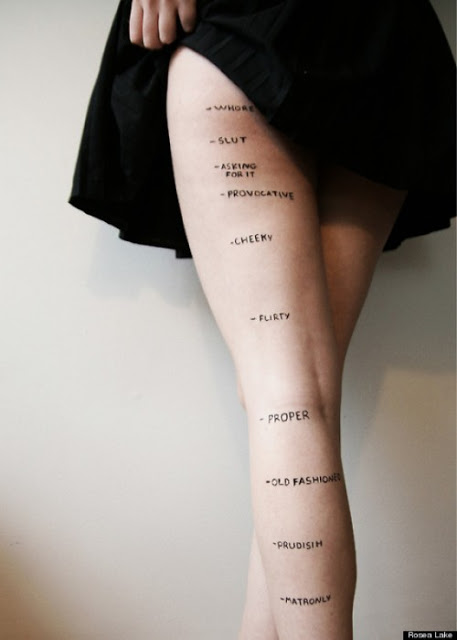

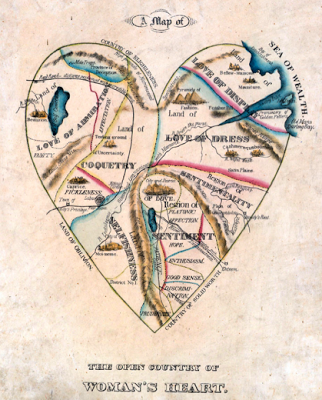

I write here about beauty: conventional prettiness, the beauty of the individual, the work we put into our appearance. But sometimes I lose sight of what’s at the heart of beauty work: the desire to be seen in the way we wish to be seen.

In other words, our desire for beauty is often a desire to determine our image. How better to do that than to keep a tight control on the tangible images we supply to the world? Not for beauty’s sake

—even the best portrait of me won’t turn me into Helen of Troy

—but for the sake of the traits we think make us who we are. The images we select for sharing (or at least don’t quietly untag ourselves from on Facebook) are a better indicator of how we regard ourselves than the retouching we might do on any of them.

When we start talking about sharing photographs through social media, the importance of the photographs themselves diminishes in comparison to the sharing of them. Social media encourages us to fashion our identities through editing and telegraphing our tastes: Since we can’t list every musician we like, by selecting only a handful we’re telling the world that

these are the tastes that

really form who we are. It doesn’t matter if you know I like Fleetwood Mac, but if I don’t put out there that I’m a jazz fan, a crucial part of my taste identity is missing. (Actually, I deleted all my tastes from Facebook and now only “like” musicians and such whom I’m friends with, but even that’s another form of telegraphing something:

Nyah nyah, you don’t know anything about me.)

In the same way, the photographs we choose to share of ourselves form another arm of our public identity

—and because of the primal power images have, they take up more psychic room than listings of our favorite bands. How good we look isn’t the most important factor in deciding what photos of ourselves to publish, if my quick perusal of some friends’ Facebook photo albums applies across the board. Activity appears to be king: weddings, birthdays, big nights out, costumes, social gatherings

—these are the photos Facebook showcases, not merely our sleekest, most groomed selves. For that’s the point, right? That Facebook allows us to share our real lives?

But what that actually does is further the onus on each of us to only publish photos of ourselves that match the image we’d like to put forth into the world. And more often than not, that image is casual, carefree, not heavily styled

—but looking pretty damn good. And why wouldn’t it? Back when we had to pay for each print and rely on the goodness of friends who bothered to make doubles of a roll of film from a party, we didn’t have the luxury of curating only the best photos of ourselves. Now there’s no reason for us to put forth photographs of ourselves that are downright unflattering

—but more than that, there’s no reason for us to share photographs that don’t match our self-image in some way. Sometimes it can feel like there’s not even a reason to

take a photo unless it’s going to be shared, making the act of sharing transcend the details of any given photo.

If sharing a photograph can transcend the photograph itself, sometimes the photo can transcend reality, something we recognized long before we could all easily create, discard, and share photographic evidence of our lives. “It is common now for people to insist about their experience of a violent event in which they were caught up

—a plane crash, a shoot-out, a terrorist bombing

—that ‘it seemed like a movie,’” writes Susan Sontag in

On Photography, 1977. “This is said, other descriptions seeming insufficient, in order to explain how real it was.” We allow photographs to supplant memory, in part because they are static and reliable, and can be referred back to, where our memories become muddled. In the same way, portraits of ourselves become static, reliable externalizations of who we think we are, where our identity can become muddled. Beyond the awareness that everyone from our siblings to our employers to our exes might be able to see whatever images we put online,

the most important recipient of the self-image telegraph we send through sharing photographs is ourselves. Photos become proxies for what we believe to be true of ourselves, and seeing a photograph of ourselves can serve as assurance that we are who we think we are

—or, as anyone who has ever felt their heart fall a little upon seeing an unflattering photo of themselves knows, that we

aren’t who we think we are.

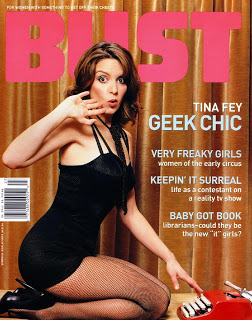

But because photographs are often shared beyond our most important audience

—ourselves

—it feels important to “keep it real” and not put forth unrealistically beautiful images of ourselves either. If, as Tina Fey put it, feminist Photoshopping is retouching that makes you look “as if you were caught on your best day,” then social-media photo curation is making sure we’re shown in what appears to be a somewhat-but-not-remarkably-better-than-average day. The idea is that we’re captured as-is (even when we’re not); it’s part of the seamless sharing of self Facebook is designed for.

And because of the supposed seamlessnes of our online and offline lives, if I put forth only my most luminous, well-styled, color-corrected portraits, the people who know the real-life non-color-corrected me can privately call bullshit on me, and I know they can. We each become our own photo editor, striving to make sure we look good but not too good in the photos we put into the world. (For the record, I have done the math and my public photos have a 12% bias toward being flattering. Those of you who haven’t met me, please adjust your mental image accordingly.)

Yet the question of how pretty or not pretty we look in the images we release to the world has become secondary to the question of self-curation.

I don’t mean to say that we’re all anxiously poring over our photographs with a constant eye on our public image—but I’ve gotta say that when I looked at the photographs that I’ve actively shared of myself on Facebook, they don’t really resemble my actual life. (Arguably the photos others have posted and tagged me in are more realistic

—but then, of course, I’m out on the town or in another situation that calls for a camera.) The pictures I’ve posted of myself reflect a side that I’d like to shine more brightly than it actually does: a seasoned traveler who’s up for anything, whether that be eating a horse burger in Slovenia, pouring a tray of mojitos for my coworkers, or riding a mechanical bull in midtown. (

Ahem.)

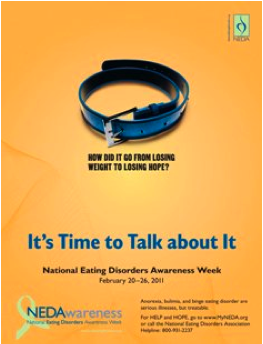

In fact, my very favorite photo of myself

—and yes, it’s on Facebook, and indeed is my profile photo on The Beheld

—was taken toward the end of a trip I took to Vietnam. I was sitting alongside Hoan Kiem Lake in Hanoi, and a small boy started playing peekaboo with me. He seemed interested in my camera, so I took a couple of photographs of him, but he was less curious about that and more interested in operating it himself. He snapped this photograph of me:

It’s a good portrait of me because I am smiling the way I’d smile at a child with whom I’m having a delightful exchange; it reminds me of an adventuresome time in my personal history. It also happens to be a superbly, perhaps unrealistically, flattering photo. Who am I to say why I love the photo so much? Is it the memory, the light, the smile? Whatever it is, it’s become a talisman for what I would like to be true of myself: that I am not annoyed when a four-year-old wants to play with me, that I have unlimited time to lounge about southeast Asia, and, yes, that I’m constantly illuminated by a subtropical glow that emphasizes my suntan. I can’t claim that image is an accurate representation of me, but it’s what I offer myself. And it’s what, today, I offer to you.