In the late fall of 1991, my friend Tony gave me a ride home from school. As we settled into the seats, he pushed in a tape, and I heard this jangly guitar—it sounded like it was barely plugged in, or something, somehow off, somehow disconnected—followed by this aggressive, to-the-point kick of the drums. The intro turned into the actual song, with this voice chanting Hello, hello, hello, how low?, and without knowing what I was listening to, I felt something within me twist. I could barely understand the words, but I didn’t need to; the chords, or rather the discord, said all I needed to hear. The cynicism, the apathy, the longing, the anxiety, the edge of eruption—I felt it before I heard it, and it made me want to do something. What, I didn’t know exactly, but I felt immediately and intensely uncomfortable, the kind of discomfort you feel because you know, acutely and irrevocably, that something needs to change.

But instead of doing something, I just turned to Tony and asked what we were listening to. “This is Nirvana,” he said.

Then, as now, I rarely listened to new music, preferring my parents’ Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, and Blood Sweat & Tears. So I wasn’t surprised that I hadn’t heard Nirvana before, even though I’d been hearing about the band for months around school; I’d assumed it was like other buzz-generating music (which, at the time, was Vanilla Ice, if that gives you an idea of the popular music scene at my suburban high school). What surprised me was how much a part of it—whatever “it” was—I felt. Without knowing it, I was a part of the zeitgeist.

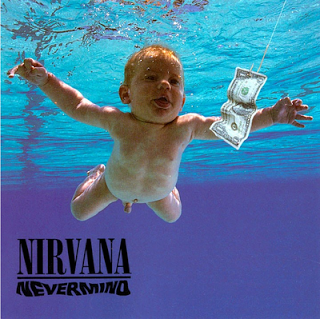

This week marks the 20th anniversary of the release of Nevermind, so I’ve been thinking about the stirring I felt in my friend’s car. When I remember how “Smells Like Teen Spirit” resonated with me without me knowing that I was listening to The Band That Was Changing Everything, I have to credit factors larger than either Nirvana’s musicianship or my own musical sensibilities. Without blathering on about what people far more qualified than I have already written about the disillusionment of GenXers: I’d seen the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Rodney King videos, Exxon Valdez, Jeffrey Dahmer, Magic Johnson’s AIDS announcement, and Nintendo. I’d seen my country invade another for reasons that were unclear to me, this after my enchantment with an earlier era in which our country invaded another for reasons that were also unclear to me, and the main difference seemed to be that while our parents took to the streets, my generation—including me—was doing jack shit. I don’t want to overstate the case here, but we had a lot of reasons to be cynical, withdrawn, and discordant. There was a reason I heard those jangly guitar chords and instinctively knew they meant something.

Now, there’s been plenty of ink spilled over what Generation X really was, and if the whole apathy/cynicism bit really held true or if it was just a handy marketing tool, or what. All I know is that I was a product of the early ‘90s, and it showed in the way I dressed myself and put on makeup: Believe me, I cared fiercely about how I looked. But the ways in which I was trying to look good reflected what was going on at the time. I was earnest about wanting to be seen as pretty, but lackadaisical about how stringent I needed to be to get there. I styled my hair by teasing it a little bit up front and brushing it constantly, but except for special occasions there were no curlers involved, and flatirons were seen as extravagant. Few of us wore foundation, though we agonized plenty over our pimples and tried as many concealers as our allowance would allow. I thought I was freaked out over body hair, but really I just felt normal teen-girl embarrassment about the stray hairs on my upper lip—a “bikini line” in 1991 truly meant the line of a bikini, tweezing stray hairs when we’d go swimming and not giving a damn the rest of the time. We didn’t wear much blush; it looked too...healthy. We didn’t reject fashion and beauty by any means—I spent hours in front of the mirror trying out various hairstyles, none of which ever saw the light of day—and we eagerly gobbled up products geared toward us. (Bonne Bell Lip Smackers survived the grunge era.) But our laid-back ethos seeped into our self-presentation. We didn’t know what tooth-bleaching was.

Spot the '90s! 1) Flannel around my waist. 2) Tucked-in T-shirt. 3) Cutoffs over hosiery. 4) VHS tape pile topped by Stephen King books. 5) Tie-dye. 6) Converse (in background). 7) Black eyeliner applied after melting tip of eye crayon with lit match to make it go on heavier/messier. 8) Pendant (you can only see the chain in pic #3 but trust me, there was a big ol' ankh at the end of it). 9) Small flower pattern dress. 10) Smirk.

* * * * *

I still think that the roots of appearance anxiety are essentially the same for a 15-year-old girl today as they were for me when I was doing jumping jacks alone in my bedroom to the B-52s. Girls are succeeding just a little too much to maintain the status quo; all the better to feed them diets and eyelash extensions to keep their eyes on a different prize. But it wasn’t until I gave some thought to that moment in my friend’s car that I thought about the ways other cultural forces shaped the way I regarded my grooming choices. If the ethos of my time seeped into my way of presenting myself, that means the ethos of today’s time is doing the same thing. And I know I’m probably late to the party here—yo, Madrano, things have been harder on girls for a while now—but if the ethos of today is about putting a heavier premium display and individuality through appearance (Lady Gaga, anyone?), that’s worming its way into girls’ minds in ways my generation was spared.

If you watch The X-Files today, it’s shocking how ill-fitting and shapeless Scully’s clothes were in 1992; no wonder people freaked out about the length of Ally McBeal’s skirts in 1997 (which, for the record, now seem totally normal). Compare wardrobes of The Real World with that of The Jersey Shore. And does anyone remember the fashion item that Julia Roberts made enormously popular in 1991? Blazers. And not cute little cropped blazers, but loose men’s-style blazers that enveloped my teenage body, giving it relief from being appraised for the size and shape of what was underneath.

I don’t have any sort of treatise here; I don’t think that returning to 1991 would necessarily do us much good. Hell, the retro-grunge fad from a couple of years ago showed that: Millennials were told to achieve the grungy bedhead style through products. (The truth is, most of us in the early ‘90s just didn’t do a damn thing to our hair except dye it with Manic Panic, or, for those of us less committal, Kool-Aid. We weren’t nearly as greasy as today’s magazines would have you believe.) In some ways this post may just be a mea culpa to the world at large for not having paid closer attention to the differences between what young women experience today versus my experience as someone who came of age at a time when baby tees hadn’t yet been invented. I maintain that the root issue isn’t that different. But more has changed than I realized.

There was plenty working against teenage girls in 1991, which is part of why I felt so anxious about how I looked back then even though the end result of my efforts were of the times—low-key, a tad sloppy, free-flowing. But I’m only now realizing how much was working for us back then too.