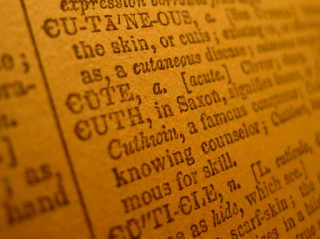

Cute began as a shortened form of acute, meaning a sharp, quick intelligence or cleverness. In the 1830s, it became slang for pretty in the American South—specifically a diminutive prettiness, retaining the piquant playfulness implied in the word’s original meaning. As late as the 1890s cute still meant clever in the north, as well as the British Isles, where it became slang for pretty only in the mid-20th century. But cute worked its way north quickly enough for The Nation to decry its overuse in 1909: “The reviewer will also ever pray in the interest of the English language...that the word ‘cute’ be banished from the pages of serious literature,” and Emily Post followed suit in 1927, calling cute “provincial.”

The Great Depression brought a backlash against not the slang of cute, but the concept itself. “In this changing world, the ‘sweet girl’ and the ‘cute girl’ belong to the past,” read ads for a 1935 mail-order “charm test” from actress turned charm expert Margery Wilson. It wasn’t just a sales pitch: Leading ladies like Jean Harlow, Barbara Stanwyck, and Bette Davis were bringing an adult sensibility to the screen that 1920s cutie-pies like Clara Bow and Lillian Gish couldn’t. The “cute girl” wasn’t necessarily going to help out the economy either; as with today’s recession, men’s jobs in the Depression were hit disproportionately, leading more families to depend upon women’s wages than ever before. “The women know that life must go on and that the needs of life must be met,” said Eleanor Roosevelt in her 1933 book, It’s Up to the Women. “It is their courage and determination which, time and again, have pulled us through worse crises than the present one.” Cuteness wasn’t an asset; the steely strength of Harlow-style glamour was to pull the nation through.

With economic recovery returned a longing for the cute girl: In 1944, the same year that U.S. unemployment hit its lowest-ever mark of 1.2%, scripts for radio show Meet Corliss Archer saw quips like “Trade you all the Lamours and Lamarrs in the world...for a cute girl who can wear gingham and isn’t afraid to giggle. Glamour’s too rich for my blood.” The 1950s embraced cute, bringing ever-more appendages to the word: A woman might be a “cute thing,” “a cute trick,” “a cute dish,” “a cute number,” “a cute little piece,” “a cute chick,” “a cute doll,” or “a cute little bug” (of course, the latter is Robert Heinlein describing a parasitic invader from outer space, but he’d also called said bug a brunette, so I think it’s fair use here). By the 1960s, cute was in opposition not just to glamour but to sex itself. “The ‘cute girl’ is viewed as the friendly, ‘all-American girl’... She is vivacious, attractive, and, above all, not overly interested in the leverage one can obtain over boys through the judicious allocation of her affections” (American Journal of Sociology, 1967). Or, more bluntly: “Both our male and female informants define a ‘cute’ girl as a person who exudes a certain kind of sexual attractiveness but who does not demonstrate her sexual superiority in intercourse” (Studies in Adolescence, 1969).

The desexualization of cute makes it particularly useful in certain instances. It’s one of the few terms of appearance we freely apply to both sexes. We also use it for children, animals, and the elderly—the latter of whom are undoubtedly not thrilled to be in the company of the former two. In fact, many a cute person well within the childbearing years may be vexed by cute. “I have remained cute for far too long, and that is not bragging,” writes wide-eyed, freckled Heidi Schatz. “By golly, I will try on lingerie until I no longer laugh when I see myself in the mirror.” The teenage male protagonist of Judy Blume's best-known book for boys, Then Again, Maybe I Won’t, weighs in after his objet du désir calls him cute: “Why do girls always say cute? That’s such a dumb word. It makes me think of rabbits.” In fact, when used by girls about boys, it’s that very harmlessness that makes it an appealing word, for the same reason the wholly unthreatening Justin Bieber went platinum. What 12-year-old girl wants the Handsome Young Men’s Association when you can have the Cute Guy Club?

Why yes, that is Sugar Ray.

The diminutive application of cute can make it a weapon: A person labeled as cute may be seen as unserious or childlike, in addition to desexualized. But that’s also what makes it safe. Cute as a weaker term for attractive allows for some reserve: A noncommittal teenage boy might say it about a girl without appearing foolish; adults might use it as a disclaimer (“He’s cute, but...”). Because cute isn’t a threat, we can sprinkle it liberally throughout our conversations without seeming to make a pronounced statement. Cute shoes, cute dress, we tell strangers. Cute haircut, we may say to friends, regardless of how flattering the trim actually is. We can use cute for ourselves without seeming arrogant. I’ve heard friends say “I look cute” about themselves far more freely than they’d use pretty or beautiful, and even though cute isn’t a word I often hear from others about myself (is it the alto voice?), saying I’m cute feels like far less of a risk than saying I’m pretty. It’s a softened form of acknowledging general attractiveness—ours or someone else’s—without making judgments about God-given features.

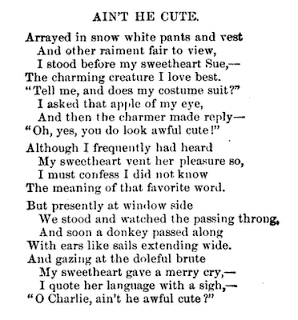

Cute, I suspect, is a word whose likability decreases in direct proportion to how often you’ve heard it applied to yourself—the liveliness connoted by cute may be refreshing to the speaker, and tired old news to the wide-eyed, apple-cheeked lass who’s heard it for the twelfth time that day. On the rare occasion I’m called cute, it pleases me in the way that being called charming does: I take it as a statement of the moment, that for whatever reason the other person sees me as cute because I’m doing something uncharacteristically naive. I don’t internalize it as an indicator of my womanhood or sex appeal—a luxury I’ve been given because, as I lack the stereotypical hallmarks of “cute,” I’ve never had it used to undermine me. Yet I remember my petite redheaded pixie-faced college roommate publicly cursing cute, and as her cheeks got rosier and her pitch got higher in complaint I caught myself (to my shame) replaying that ever-undermining phrase in my mind: Gee, you’re cute when you’re mad. A blue-eyed, curly-haired friend of mine makes a point of showing cleavage as a rebellion against the years she was swaddled in 1970s high-necked doll-style clothes that emphasized her childhood cuteness, and there’s even an entire Facebook group devoted to those who Hate Being Called Cute. But the most poetic rebellion against cute comes from turn-of-the-century scribe Wesley Stretch, who duly synthesized the complaints about the desexualization of cute: