From Head...

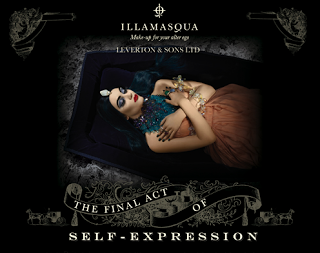

I'll tweeze when I'm dead: Postmortem makeup service allows you to choose your own cosmetics for your final performance. I actually think this is sort of brilliant, and if I'm buried in a casket I'd like some assurance that people's last visions of me won't be with, say, eyeshadow. Not that I'll be buried in a casket, for I plan on being cryogenically frozen.

Ginseng-fed snails on yer face: I suppose once you're slapping snail slime on your face it's all the same, but I'm somehow more bothered by the fact that these snails destined for face creams are fed a diet of red ginseng than the fact that they're being used at all. How did that meeting go? "Gee, Bob, how can we maximize the benefits of putting snail slime on our wives' and daughters' faces?" "Well, Bill, we can feed the snails ginseng first." "Bob, old boy, that's damned brilliant. Golf?"

...To Toe...

Trend investigation: Interesting collection at the NYTimes of mini-essays from a variety of thinkers on why wild nail polish (I prefer mine on my feet, staying classic with the manicure) has strayed from its alternative/punk roots into the mainstream.

...And Everything In Between:

Motivations behind the increase of diversity among models: Surprise—it's money, not a global handshake! Also some fascinating tidbits about global beauty habits, like urban Mexican women mixing crushed birth control pills into their shampoo to combat pollution-related hair loss.

"You can't learn how to be elegant; you can only learn how to avoid mistakes": Great Q&A with Carine Roitfeld (former French Vogue editrix); she refers to her reign there as a "gilded cage" and has some choice bits on the globalization of fashion. (Thanks to the new spiritual geography blog Deep Map for the heads-up.)

Look chic without dead animal skin!: Makeup artist Eden DiBianco for GirlieGirl Army on a "vegan" version of the snakeskin manicure that is inexplicably popular now.

Is your shampoo making you gain weight?: You'll rarely see me contributing to any OMGZFAT! brouhaha, but the idea of endocrine disruptors in shampoo contributing to weight gain freaks me out for reasons that have nothing to do with my thighs. If a chemical is making me gain weight...what else is it doing?

Man makeup: Feminist-minded piece on men exploring fanciful dress and makeup. The piece's thesis is that it's allowing men to be more playful than in recent history; not sure how that jibes with Hugh Laurie's recent endorsement for L'Oréal, which pretty much relies on his masculinity for its success. Like most aspects of high fashion I don't see men cross-dressing in the mainstream yet, but since men's cosmetics sales are on the uptick it's not like the worlds are entirely separate either.

Shave it for cancer: Ladies, do you feel left out of Movember, the moustache growing month that somehow magically raises funds for kids with cancer? Good news: The Canadian Cancer Society has come up with Julyna, during which we're to groom our pubic hair in interesting shapes to raise money for cervical cancer. Can't I just have a bake sale instead? (I'm with About-Face in thinking this is a terrible idea, but got a kick out of their "example designs" page. The "side part"?)

I bleed red: Always dares to show a red dot in a maxipad ad. Egads! Also in menstrual news, my gym has started giving out coupons for Playtex Sport tampons, which is a good thing, because I didn't realize that I needed a special menstrual product for playing sports. All this time I've been using office-worker tampons! Watch it, Venus, I'm onto your wily ways.

Real women on "real women": Great two-part collection of thoughts from fashion and beauty bloggers (yours truly included) on the term "real woman," put together by the fantastically community-minded Beautifully Invisible. (She's also recently launched Full-Time Ford, a blog devoted to exploring the work of designer Tom Ford. I know exactly zero about Tom Ford but those of you who are fans should check it out!)

The conflicted self in body image blogging: Demoiselle's meta-examination of body image blogging and the traps it can lay for its explorers: "Many of these methods and paths that self-acceptance movements are taking are very exclusive and comparison-based."

"On Makeup": Britt Julious of Britticisms, with quiet devastation, delivers as usual in her personal history of makeup.

"You know you're the prettiest girl": Rob Horning at The New Inquiry on the Laurel Nakadate exhibit at P.S. 1: "...we be pushed into acknowledging the place Nakadate seems to want to reach, where the integrity of how you feel about yourself, the possibility of recognizing the sincerity of your own emotions, is sacrificed to the need to be looked at."

Race, class, and street harassment: Excellent post (that I'm late to discover) on the role of class in street harassment. "We're fond of saying that the victim's perception is the key element in determining whether or not a person has been harassed, and while I mostly agree with that sentiment, how does that square with the knowledge that some of our perceptions are a product of the values and norms we subscribe to that are determined by economic class?"

Makeover (and over and over): Hypnotic video in which a year's worth of makeup is applied to a woman's face. Some Jezebel commenters see this as a critique of the beauty industry; I just thought it was sorta nifty?