The earliest mention of cankles in written matter has nothing to do with either calves or ankles. Chosen not for its imagined meaning but for its terrific dissonance, c-a-n-k-l-e was deemed so ludicrous by sci-fi writer Don Webb that he chose it as the premise of “Late Night at Webster’s,” a 1996 postmodern essay envisioning how new words enter the dictionary. “A word was dropped in their midst. It was cankle,” the essay begins, with his imagined characters bantering back and forth, "Canker and ankle. A foot sore." "Canner and baker. A grandmother." "A compound, can and kill." “I move that cankle is a dead metaphor.” "I can't picture Goethe saying cankle." It’s lunacy, and that’s the whole point, for who would ever take cankle seriously?

And yet, as we know, we did take the cankle seriously. So I began to research its early usage outside of postmodern sci-fi essays—and here, Dear Reader, I have a shocking confession: I am the Oedipus of cankles.* I started researching early uses of the word in an effort to point a triumphant finger and say, This is where it began! Behold Pandora's box!—and found that the earliest print usage of cankle as an actual word was in a 2003 issue of Glamour magazine that I’d copyedited. I could have abandoned cankles on a mountaintop, Jocasta-style, but instead I chose sympathy and let it thrive—and here, today, in front of you all, cankles has come back to wed its blogmother.

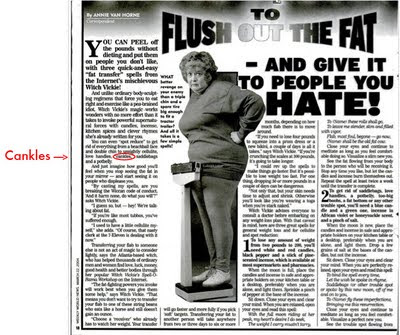

The copy reads, "It's a genetic fact: Some women have cankles—thick, calflike ankles." I remember feeling uneasy about the word at the time, and also feeling powerless to speak up; supposedly clever wordplay was the premise of the piece, which was a roundup of words Glamour came up with to describe various appearance-related phenomenon, like deep fryer for a woman who overtans. (In truth, I was a young freelance copy editor and there's no way anyone would have taken it out on my say-so, but I prefer to think of myself in a tragic Hellenic fashion here.)

In any case, I was deeply relieved to learn that cankles had an earlier appearance in a more appropriate setting—2001’s Shallow Hal, uttered by Jason Alexander’s superficial character. So Glamour didn’t coin the term (and I can’t be certain that Glamour marked its print debut, but I’m unable to unearth anything earlier), but the magazine did take cankles from its purposefully loopy origins—as something said by a character whose comedy stems from his inability to see anything but someone’s adherence to a conventional beauty standard—and made it something we’re supposed to be legitimately concerned about. Certainly Glamour helped tip it from the realm of comedy into the mainstream: By 2006, cankles had made it into Men's Health, Women's Health, Newsweek, Skinny Bitch, a small library of novels and un-noteworthy books, and the Weekly World News, which recommended a magic spell to get rid of them (it involves the new moon, African violet, and visualizing your cankles going to a person of your choosing).

Really, though, cankles aren’t the least of it. I’m focusing on cankles because it’s Portmanteau Week here at The Beheld (I encourage everyone to celebrate Portmanteau Week with me; we'll make appletinis!), but my concerns here are broader: love handles, saddlebags, potbellies. Muffin-tops, bat-wings, back bacon, FUPA (which is thankfully little-known outside of people who make a sport out of shaming women’s bodies, so I won’t get into its acronym here). Hell, to keep it on point with portmanteaus, we have ninkles, which barely qualifies as a portmanteau (if we—"we," of course, meaning the British Vogue editor who coined the term and exactly no one else ever—must come up with a word for knee wrinkles, can’t we have it be kninkles?) We keep coming up with these terms to describe parts of women that are perfectly normal parts to have, or that indeed aren’t a part of their bodies at all—even the slenderest of women will have a “muffin-top” if her pants don’t fit right. We name it to shame it.

We’ve gotten quicker to name these wobbly bits, and we’ve gotten meaner too. Love handles, which originated in the late 1960s, is generous to that bit of flesh above the hips—the term implies that maybe we’re to be adored, and then handled, for having it in our possession. We may still wish to exercise them away, but they’re endearing, and its usage implies affection. “His girlfriend grabbed the rolls around his middle and playfully christened them love handles” (Dr. Solomon’s Easy, No-Risk Diet, 1974); “I kissed Alex, putting my arms around the bulges above his waist, the ones my mother always called love handles” (Galaxy magazine, 1975).

So with love handles being too full of, well, love, muffin-top came in as a handy replacement for it, right along the time we started hearing shrieks about the obesity epidemic (and, of course, abdominal obesity, which can “strike” even slim-seeming Americans). Muffin-top is talk-cute, no doubt, but there’s a meanness to it that I don’t sense with love handles. William Safire disambiguates love handles from muffin-top by saying that the muffin top is more circular as opposed to being strictly on the sides, as with the “handles” in love handles. That’s part of it, but it’s not the whole story. Muffin-top is specifically a term about how people look when they’re dressed—its very definition relies upon flesh spilling over a waistband. Love handles is specifically a term about how people might possibly be touched—amorously—when they’re undressed.

“We have terms like sexual harassment and battered women,” wrote Gloria Steinem about the progress of feminism in her 1979 essay “Words and Change. “A few years ago, they were just called life.” The inverse intent holds true too: If naming domestic violence allows us to go about fixing it, what does that do for cankles, which were once just called life? Every time we use a word like cankles to describe bodies—our own or other women’s—we give them more power than they merit. The entire purpose of these supposedly cute words isn’t to nullify women’s shame about our bodies; it’s meant to amplify it.

In some cases, these words are developed to create shame where there wasn’t any, which is another neat trick of these terms—most of the time, we don’t really know if we possess the dreaded words. Do I have saddlebags, or do I just have hips? Do I have bat-wings, or are my upper arms merely fleshy? Do I have back bacon, rolls of porcine flesh spilling out over my bra band—or do I just need a better bra?

The naming problem applies across the board, but the portmanteaus here seem particularly egregious. Portmanteaus fill a need, or describe something that’s already happening. When they’re created not to label an existing phenomenon that begs discourse—say, e-mail—but to create a demand, it’s usually a corporation that’s doing the naming: Verizon, Rolodex, Amtrak, Texaco. But with the ugly little portmanteaus (portmanteaux?) we use to describe body parts, The Man isn’t benefiting. Sure, big business is known for inventing problems so that they could be solved; eyelash hypotrichosis (conveniently solved by Latisse!) is my personal favorite. But other than Gold Gym’s 2009 “Cankle Awareness Month” and a couple of ebooks titled things like "Say Goodbye to Cankles," businesses aren’t benefiting from these specific words of body policing, even as many of them funnel money into the weight-loss industry. So if the corporations aren’t winning with cutesy terms like cankles, who is?

*Actually, if we're going to get all word-nerd here, Oedipus is the Oedipus of cankles. The poor babe was bound at the ankles by his father so that he couldn't crawl, then abandoned on a mountaintop so that he wouldn't survive in order to fulfill the Oracle's prophecy of marrying his mother and killing his father. Oedipus was rescued by his adoptive parents, who named him for his swollen feet and ankles: Oedema is the ancient Greek word for swelling. (It's where edema comes from, incidentally.)

And yet, as we know, we did take the cankle seriously. So I began to research its early usage outside of postmodern sci-fi essays—and here, Dear Reader, I have a shocking confession: I am the Oedipus of cankles.* I started researching early uses of the word in an effort to point a triumphant finger and say, This is where it began! Behold Pandora's box!—and found that the earliest print usage of cankle as an actual word was in a 2003 issue of Glamour magazine that I’d copyedited. I could have abandoned cankles on a mountaintop, Jocasta-style, but instead I chose sympathy and let it thrive—and here, today, in front of you all, cankles has come back to wed its blogmother.

The Finding of Oedipus, French School, 17th or 18th century.

To think I was once as naive of my role in cankles as Oedipus was here of his

filial relation to his bride Jocasta. O innocence!

filial relation to his bride Jocasta. O innocence!

The copy reads, "It's a genetic fact: Some women have cankles—thick, calflike ankles." I remember feeling uneasy about the word at the time, and also feeling powerless to speak up; supposedly clever wordplay was the premise of the piece, which was a roundup of words Glamour came up with to describe various appearance-related phenomenon, like deep fryer for a woman who overtans. (In truth, I was a young freelance copy editor and there's no way anyone would have taken it out on my say-so, but I prefer to think of myself in a tragic Hellenic fashion here.)

In any case, I was deeply relieved to learn that cankles had an earlier appearance in a more appropriate setting—2001’s Shallow Hal, uttered by Jason Alexander’s superficial character. So Glamour didn’t coin the term (and I can’t be certain that Glamour marked its print debut, but I’m unable to unearth anything earlier), but the magazine did take cankles from its purposefully loopy origins—as something said by a character whose comedy stems from his inability to see anything but someone’s adherence to a conventional beauty standard—and made it something we’re supposed to be legitimately concerned about. Certainly Glamour helped tip it from the realm of comedy into the mainstream: By 2006, cankles had made it into Men's Health, Women's Health, Newsweek, Skinny Bitch, a small library of novels and un-noteworthy books, and the Weekly World News, which recommended a magic spell to get rid of them (it involves the new moon, African violet, and visualizing your cankles going to a person of your choosing).

Really, though, cankles aren’t the least of it. I’m focusing on cankles because it’s Portmanteau Week here at The Beheld (I encourage everyone to celebrate Portmanteau Week with me; we'll make appletinis!), but my concerns here are broader: love handles, saddlebags, potbellies. Muffin-tops, bat-wings, back bacon, FUPA (which is thankfully little-known outside of people who make a sport out of shaming women’s bodies, so I won’t get into its acronym here). Hell, to keep it on point with portmanteaus, we have ninkles, which barely qualifies as a portmanteau (if we—"we," of course, meaning the British Vogue editor who coined the term and exactly no one else ever—must come up with a word for knee wrinkles, can’t we have it be kninkles?) We keep coming up with these terms to describe parts of women that are perfectly normal parts to have, or that indeed aren’t a part of their bodies at all—even the slenderest of women will have a “muffin-top” if her pants don’t fit right. We name it to shame it.

We’ve gotten quicker to name these wobbly bits, and we’ve gotten meaner too. Love handles, which originated in the late 1960s, is generous to that bit of flesh above the hips—the term implies that maybe we’re to be adored, and then handled, for having it in our possession. We may still wish to exercise them away, but they’re endearing, and its usage implies affection. “His girlfriend grabbed the rolls around his middle and playfully christened them love handles” (Dr. Solomon’s Easy, No-Risk Diet, 1974); “I kissed Alex, putting my arms around the bulges above his waist, the ones my mother always called love handles” (Galaxy magazine, 1975).

So with love handles being too full of, well, love, muffin-top came in as a handy replacement for it, right along the time we started hearing shrieks about the obesity epidemic (and, of course, abdominal obesity, which can “strike” even slim-seeming Americans). Muffin-top is talk-cute, no doubt, but there’s a meanness to it that I don’t sense with love handles. William Safire disambiguates love handles from muffin-top by saying that the muffin top is more circular as opposed to being strictly on the sides, as with the “handles” in love handles. That’s part of it, but it’s not the whole story. Muffin-top is specifically a term about how people look when they’re dressed—its very definition relies upon flesh spilling over a waistband. Love handles is specifically a term about how people might possibly be touched—amorously—when they’re undressed.

“We have terms like sexual harassment and battered women,” wrote Gloria Steinem about the progress of feminism in her 1979 essay “Words and Change. “A few years ago, they were just called life.” The inverse intent holds true too: If naming domestic violence allows us to go about fixing it, what does that do for cankles, which were once just called life? Every time we use a word like cankles to describe bodies—our own or other women’s—we give them more power than they merit. The entire purpose of these supposedly cute words isn’t to nullify women’s shame about our bodies; it’s meant to amplify it.

In some cases, these words are developed to create shame where there wasn’t any, which is another neat trick of these terms—most of the time, we don’t really know if we possess the dreaded words. Do I have saddlebags, or do I just have hips? Do I have bat-wings, or are my upper arms merely fleshy? Do I have back bacon, rolls of porcine flesh spilling out over my bra band—or do I just need a better bra?

The naming problem applies across the board, but the portmanteaus here seem particularly egregious. Portmanteaus fill a need, or describe something that’s already happening. When they’re created not to label an existing phenomenon that begs discourse—say, e-mail—but to create a demand, it’s usually a corporation that’s doing the naming: Verizon, Rolodex, Amtrak, Texaco. But with the ugly little portmanteaus (portmanteaux?) we use to describe body parts, The Man isn’t benefiting. Sure, big business is known for inventing problems so that they could be solved; eyelash hypotrichosis (conveniently solved by Latisse!) is my personal favorite. But other than Gold Gym’s 2009 “Cankle Awareness Month” and a couple of ebooks titled things like "Say Goodbye to Cankles," businesses aren’t benefiting from these specific words of body policing, even as many of them funnel money into the weight-loss industry. So if the corporations aren’t winning with cutesy terms like cankles, who is?

*Actually, if we're going to get all word-nerd here, Oedipus is the Oedipus of cankles. The poor babe was bound at the ankles by his father so that he couldn't crawl, then abandoned on a mountaintop so that he wouldn't survive in order to fulfill the Oracle's prophecy of marrying his mother and killing his father. Oedipus was rescued by his adoptive parents, who named him for his swollen feet and ankles: Oedema is the ancient Greek word for swelling. (It's where edema comes from, incidentally.)