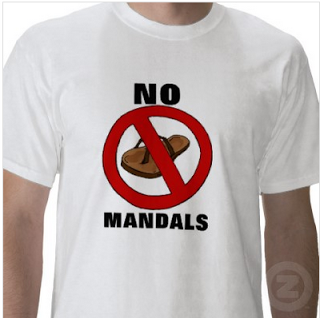

Speaking of portmanteaus, would this T-shirt qualify as anti-mandal slacktivism?

(For the record, I am all about sandals for all, Jesus-style.)

(For the record, I am all about sandals for all, Jesus-style.)

"Didn't the Greeks invent sandals?" asked a sandal-wearing male colleague the other day. (Actually, it turns out Oregonians did, thus setting the stage for the state's eventual reputation as hosting a bunch of Birkenstock-wearing, craft-brewing lovefreaks. Which, if my days at University of Oregon are any indication, we are.) His question was in context of mandals, hardly a newfangled fashionisto invention—indeed, they are merely sandals, which, at their base definition, are unisex. "Why do we insist on calling them mandals?" he asked.

Why do we, even if we generally sputter it out with a laugh, always using it self-consciously, making fun of the term even as we use it? It got me thinking about the uses of portmanteaus (a word formed by combining two other words, like brunch) in general, and how they're often invented to describe a new phenomenon that needs naming (like e-mail, motel, newscaster, or, hell, Tanzania) or something that somebody with an agenda names in its infancy in hopes of creating a demand. Whether it's a product (turducken) or a movement (blaxploitation), these words might not be coined cynically (there is nothing cynical about turducken), but when the term precedes its visibility in the culture, it begs investigation. I’ll be doing a mini-series this week on portmanteaus as they apply to gender and the body, beginning with exactly where my beach-oriented brain is at today: mandals.

In the case of mandals—and murses, and manpris (which, in all fairness, I've never heard anyone say out loud)—we seem to have cutesy portmanteaus that serve to trivialize aspects of men's lives that might bring them closer to the traditionally feminine realm. It's worth noting that early uses of mandals, notably in Carson Kressly's Off the Cuff, refer to a specific type of thick-soled sandal that Kressly refers to as "way too lesbian hootenanny" and that the authors of Is Your Straight Man Gay Enough? (!) call "rough and tumble sandal imitations." Presumably in its origins there was still a little wiggle room for a dignified sandal, a structured, manly, Italian-style slip-on that would allow American men to walk through heated summers with a little breeze between the toes. (In fact, early excavations of mandal find it necessarily paired with the admonition about not wearing them with socks, which, frankly is just good common sense.)

Now, however, that distinction has been lost—it's every mandal for itself, whether it be sleek and leather or rubber and chunky. My question is: Who benefits from mandal, murse, and the like? (I am tempted to include jorts, which, judging from the subjects of Jorts.com, are strictly worn by men, but the word itself remains gender-free, the hir and ze of the jeans shorts world.) Companies aren't using the term murse or mandal to sell, well, murses and mandals; they're using the perfectly good preexisting terms such as bag, satchel, messenger bag, etc. (Which, for the record, are all words women use as well for what we carry as well. I carry a midsize leather bag with internal pockets and mid-length shoulder straps designed to be worn on the shoulder, so it's distinctly a purse, not, say, a tote bag, messenger bag, satchel, or backpack—all of which might be called a murse if it were carried by a man.) In fact, if you Google murse or mandals, you'll find not links to actual bags and shoes, but criticism or praise of the items. "The Horror of Mandals," writes the Phoenix New Times. "There needs to be sand beneath your feet, or your name needs to be Matthew McConaughey,” says a source in The Daily Beast's mandals piece. On the flipside, Internet celebrity William Sledd proclaims, "I love my murse!" Of course, Sledd is best known for his "Ask a Gay Man" YouTube series, thus lobbing man-bags right into the arena of sexual identity—not because he's gay, but because he's saying this very pointedly in the persona of a gay man. (And thus we come full circle back to Carson Kressly, whose Queer Eye for the Straight Guy now seems downright quaint.)

So the companies aren't directly benefiting. You could argue that the terminology exists because of a demand for men's sandals and bags (I can't find numbers on whether sales of these items have increased in recent years), and that might be true, whether it's consumer- or company-driven—but I can't imagine that belittling terminology would actually help sales. At the same time, you don't hear the people wearing murses and mandals using the terms with a straight face—in fact, nobody says it with a straight face. These terms exist to make it clear that we as a culture are willing to cut men a little bit of slack about borrowing from the feminine sphere, but not without hazing them first. We'll allow men to wear shoes that offer a bit of relief in sweltering weather; we'll allow men to carry a bag so that they're not jamming everything into their pockets—but we'll be sure to tease them, rough them up a little, let them know that their comfort comes with a price.

In short, nobody benefits with these terms of mild derision—not men, who might wish to wear sandals but know they'll have to brace themselves for some light-hearted teasing, and certainly not women, for it's our fashions that are being suddenly framed as frivolous and shame-worthy instead of practical. (I never thought twice about sandals being gendered until I heard of mandals—I'm of the "my feet need to breathe!" camp, which I know is a deeply polarizing issue, but anyway.) Surely the world has greater linguistic problems than mandals, but I think it's a term worth looking at if we're trying to work our way toward gender equality.

This is why I'm hesitant to say that the widening field of men's cosmetics signifies any sort of progress in loosening gender roles, even as some spot-on feminist thinkers stake their claim otherwise. It's lovely to think that the boom in men's skin care means that we're slowly working our way toward allowing men access to the same realm of fantasy and play that we grant to women through fashion and beauty. But I simply don't see that as being the case: If we as a culture can't allow men to wear shoes that expose their toes without giving them some special word that keeps them in the corner, are we really going to be able to give them shame-free access to eyeliner—excuse me, guyliner—anytime soon?