"Perfume seemed part and parcel of womanhood—its nature, invisible but sweet, sums up the expectations for women’s behavior through most of history—but the existence of cologne and aftershave blur gender lines. It isn’t just women who want to smell good. It’s people."

At noon on a hot August Wednesday, the Sephora on 34th Street is the most soothing store on the block. It’s as packed with lunchtime shoppers and tourists as the nearby Foot Locker and H&M, but the women’s faces in Sephora—and it’s almost uniformly women—have a serene cast that’s rare in Manhattan on a weekday. Fingers trail over tubes of color, eyes close trustingly as a carefully made-up employee bends over a customer’s face with a mascara applicator; toner is stroked over skin and perfume is spritzed on wrists. Feminine murmurs and coos wash through the room. It’s a sensory paradise, everything promising beauty, beauty, beauty.

“Can I help you with something?” the black-clad sales associate asks. He is a man, actually, young and acne-scarred with sculpted hair that gives off a cedar scent.

“Uh, yeah,” I respond, slow on the uptake—I hadn’t expected such slack-lidded serenity in midtown—and momentarily at a loss. But my mission has been long in the making and its purpose comes back to me quickly. His pungent hair is a good reminder.

“Where are your perfumes?”

*

An Egyptian named Tapputi was the first perfumer, circa 200 BC, and her blend was probably something powerful, as royals used it in lieu of baths. This was how I once thought of perfume: strictly for the wealthy, and outdated to boot—who needs perfume in the era of hot showers and shampoo?

“Who needs it?” was my approach to all the trappings of womanhood: lipstick felt clownish and heels made me wobble so I smiled palely and sped along in flats, cutting my own hair with the help of a YouTube video. Perfume was too fussy to even contemplate. This was all well and good for a few years after college—I had a Kerouac-wannabe boyfriend and a series of outdoor jobs—but by my mid-twenties, in the company of increasingly professional peers and a kinder, more adult, boyfriend, I started to feel…young.

And not in a good way. Not in an “I never get carded” kind of way. What I felt was more akin to middle school angst, when everyone around me got breasts and I remained boyish and boobless. Breasts eventually arrived, but the less innate transition from teen to grown woman was more elusive.

It wasn’t necessarily the lack of lipstick or perfume. Plenty of women seem self-assured without these things. But those women project the sense that they easily could wear them. For them, it’s a choice; for me, it wasn’t even an option. A bright smear of lipstick would have seemed artificial, gauche even. My boyfriend told me not to worry about it—“you’re great as you are”—but that didn’t solve the problem: I was inept at womanhood but it seemed shallow and unfeminist to care, so I didn’t do anything about it. I was paralyzed. Forever young.

“The problem with a beautiful woman is that she makes everyone around her feel hopelessly masculine,” wrote Lorrie Moore. “You are praying for your breasts to grow, your hair to perk up.” It wasn’t beauty, but others’ easy womanhood—the unthinking swipe of lipstick, the easy gait in heels—that exposed my ungainliness.

It was as if everyone else had been to a womanhood seminar without me.

I wish there was a womanhood seminar, actually. Something mandatory and solemn, a rite of passage that would firmly delineate the line between adolescence and adulthood. But, at least in the U.S. of today, we learn womanhood largely alone, taking cues from generous friends or stylish moms. My mom was a strident feminist who wore shapeless t-shirts from Goodwill and my dad’s deodorant. She’s uncomfortable with her womanly body, but she’s a great mom, and ideally my passage into womanhood wouldn’t be solely based on her tutelage anyway. Becoming part of a group—even one as broad as All Women—should involve a group. Maybe even a clubhouse, a safe space to learn, or admit to needing help. Someplace where I could close my eyes, trustingly, and let another woman tell me what eyeshadow looked good with my skin tone.

*

Wending his way through the aisles, the Sephora sales associate stops and points to a tube of lipstick in a young woman’s hand. She’s a wispy blonde, pale as milk.

“That one’s gonna be a little too orange,” he tells her. As he scans the shelves, one hand on his chin, it strikes me as appropriate that my guide through the temple of womanhood is male—we’re both outsiders here. The difference is, he really knows what he’s doing. Women trust him. In this female sanctuary, even dudes trump me.

“Try this one, here,” he says decisively, holding out a black tube with a dusky pink sticker on its base. “It’s called Obey, you’ll love it, I swear.”

Obediently, she takes it.

Some lipstick color names in Sephora: Pop Star, Private Jet, Tease, Palm Beach, Paparazzi, Tabloid, Fever, Catfight, Broadest Berry, Pigalle, Schlap, Melondrama.

We soon wash out of the color narrative (the life of Lindsay Lohan as told in lipstick?) and into the perfume section at the back left. Display cases enclose vari-colored cut-glass bottles, most done up with cursive script or bows or atomizers as big and brashly decorative as hood ornaments. These—the Marc Jacobs with the huge plastic daisies or the Versace with its crystal cap like a cartoon engagement ring—are not for me: I already know what I want, the result of months of research. But there’s no harm in smelling a few others.

“Can I try this one here, the Maison Martin?” I ask, pointing at a round bottle with an understated label, the name in typewriter font.

“Good choice,” says the sales associate. “Which one would you like to smell first? We’ve got Beach Walk, Funfair Evenings, Lazy Sunday Mornings…”

*

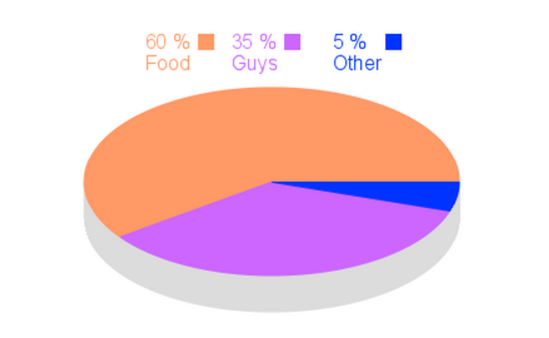

Long before I began to learn about it, I was attracted to the idea of perfume. Unlike lipstick, scent changes in contact with each individual, so finding the right one represents a real feat. This might be why people adopt a “signature scent”—it’s so much effort to find one that works with your body. (Michelle Obama apparently smells like cherries. Virginia Woolf is supposed to have smelled like woodsmoke and apples.) And unlike a pair of high heels, perfume doesn’t hobble the newbie (unless scent gives you migraines). Perfume seemed part and parcel of womanhood—its nature, invisible but sweet, sums up the expectations for women’s behavior through most of history—but the existence of cologne and aftershave blur gender lines. It isn’t just women who want to smell good. It’s people.

But while perfume was especially enticing, it was also particularly confusing. Sephora sells nearly 500 perfume varietals, while sites like The Perfumed Court stock thousands, an overwhelming array of choice. Niche stores like New York’s Bond No. 9—with less than fifty scents—weed out the objectively bad ones, celebrity scents made to smell like Jennifer Aniston’s childhood or Jennifer Lopez’s last love affair or largely reviled fragrances like Clinique Aromatics Elixir, described by one reviewer as smelling of “cats, mothballs, and fruitcakes.” But such selective stores tend to be wildly expensive and intimidating for the novitiate. You have to know something about perfume to even know they exist.

Needing a push, I mentioned my interest in perfume to one of my bosses, a stylish but intellectual woman whom I respect. It was awkward to talk about, but when trying new things, in the words of Grace Paley, “it’s as though you

have to be artificial at first.”

My boss encouraged me to look into it, supplying links to a few perfume websites. I thanked her but told her I wouldn’t know where to begin: everything had too many reviews, all of which seemed conflicting, most written in a language I didn’t understand. What were top notes? What were bergamot and chypre? How was I supposed to know what constituted a long life, perfume-wise?

Eventually, that same boss sent me an enormous book called Perfumes: The Guide, by scent experts Luca Turin (also a biophysicist) and Tania Sanchez. Their prose is acerbic and witty and damn good as they tour perfume history and basic terminology, reviewing almost 1,500 scents. A book like this was the ideal solution; allaying my fear that wanting some of the trappings of womanhood (sounding too much, to my nervously feminist ear, like “the trap” of womanhood) was a shallow, regressive goal. I read it on the train—surrounded by the far less pleasant scents of the subway—and felt saved: I was attending a womanhood seminar of one.

Perfume has a long history, but not a very celebrated one. In

Perfumes, Tania Sanchez chalks this up to two things: (1) perfume’s literal invisibility (“How could something as shapeless and evanescent as a smell have a history and a culture?”) and (2) its current status as “girl stuff.” Comparatively, the study of wine—which shares a focus on smell and descriptive language—has a well-documented history and broad appeal: People buy wine magazines, go on wine tours, and make movies about wineries. Perfume doesn’t have that kind of cachet. Perhaps that’s because wine gets you drunk.

The first man-made scents were cones of incense worn by ancient Egyptians, followed by essential oils and an herbaceous tonic called “Hungary Water,” but according to Turin the first real perfumes—alcohol-based blends of natural and synthetic fragrances—appeared in 1868, when a guy named William Perkin (who also discovered the chemical dye that produced the color mauve) synthesized a “sweet-nutty, herbaceous, tobacco-like” smell called coumarin. By 1909, synthesized scents were so popular (not to mention profitable) that the perfume counter was front-and-center in the very first Selfridge’s.

Although the many perfume blogs can be overwhelming, Sanchez and Turin explain that the internet has been good for the perfume industry. Online review sites make it harder for perfume companies to monopolize the industry, and more companies means both more innovation and lower prices. It’s democratizing: Just as everyone should be able to wear and eat what they want, everyone should also be able to smell how they want. Perfume sample sites are one of the best examples of this scent egalitarianism.

While Sanchez and Turin provide wonderful descriptions, they’re also adamant about the need to smell before buying. Ideally you’d be able to wear the same scent a few days in a row, see how it changes on your skin, get comfortable in it—like new shoes. Which makes perfume sample websites ideal: They decant a week’s worth of a scent into a vial for about $2 and ship it to your home.

But sample sites tend to provide salesy perfume descriptions, so cross-referencing is key—I made a list of good-sounding scents from

Perfumes and repaired to a sample site,

The Perfumed Court. I also started a word doc to record my findings, in the hopes that treating it like research would help me ease into my first womanhood experiment.

*

As I was selecting samples based on Turin and Sanchez’ write-ups, I realized my choices were aspirational—these were perfumes for a much more ladylike, put-together version of myself. Wood and leather scents, which I chose in droves, seemed to belong to someone who goes to the dentist regularly and doesn’t ever fall while trying to balance on the stiletto point of her heels. I added some slightly lighter scents to my cart, just to make sure I wasn't buying for, say, Katharine Hepburn instead of myself, then I made a dentist appointment while I was thinking about it.

This is one of those projects that should be inexpensive but could easily spiral out of control, as internet shopping tends to do. So I set some rules: no samples over $3, and the whole kit and caboodle had to be less than $20. I fiddled with my list, looking back and forth between the book and site, before finally settling on: Bulgari Black, Bulgari Pour Femme, Paloma Picasso, Cartier So Pretty, Missoni, and Guerlain Mitsouko. The total was $17.98. I’d receive them in 3-7 business days.

When my perfume order arrived, the packaging was as many-layered—and therefore as mysteriously elegant—as a Russian doll. Within a box was a padded envelope, within the padded envelope was a cloth sachet, within the sachet was a heavily taped mass of bubble wrap, and within the bubble wrap were six tiny vials. Because they were all touching they emanated one smell, reminiscent of my godmother's house. My boyfriend smelled it. He kind of wrinkled his nose and shrugged, “It just smells like perfume, in general.”

I placed them on our shared dresser, in our shared studio, and began what I’ve been calling “the trials.”

Day 1: The trials began with Cartier So Pretty. My boyfriend wasn't crazy about it when I put it on first thing in the morning. “You just smell all woman-ey” he said, by which I think he meant old. I told him that it changes over time on the skin and he should hold off on a final verdict until evening. In the meantime, though, I agreed with him. Still, the novelty of wearing a scent was exciting, and I kept bringing my wrists to my nose. I hoped I was wearing it right.

Day 2: Going in order from left to right, I plucked Missoni EDP from the dresser. It smelled like a really old prom corsage, plus something else, maybe dried apricots. Easily deterred (“It’s only day two,” I kept grumbling), I started to feel a little exasperated with myself. Is searching for a good scent a waste of time? Will I finish this experiment by deciding that I should just shower more frequently and buy fancier shampoo? Until then, our dresser smells like a cathedral of womanhood, and I smell like fruit and alcohol.

Oddly, when my boyfriend met me out for dinner, he actually liked the Missoni. Maybe it had faded enough by then. I asked how it smelled and he said “good” and then “it's hard to tell because it's also like you,” but then he said “fruity.”

Day 3: This morning I put on Paloma Picasso and asked my boyfriend to smell it, both in the bottle and on my wrist. “Yesterday's is still the best,” he said. “This one just smells like perfume. Like a perfume store.” And it does—it smells like the idea of perfume.

Day 4: Today I wore Bulgari Pour Femme; it's my boyfriend's favorite so far. He smelled it and said: “That one smells soft. I like it.” We went to a baseball game on Coney Island and a few times during the afternoon and evening he leaned over and smelled it and again said he liked it, unprovoked.

I’m not sure about his presence in this experiment. Recording these trials makes me more aware of the repetition: my boyfriend, my boyfriend, my boyfriend. This is in part because we share such a small space—two people sharing a Manhattan studio is no joke—and we bump up against each other a lot. And sure, I want him to like how I smell. I also think he has good taste. But it seems like relying on his opinion is a flat, boring way to come to a decision about how I'm going to smell all the time. I did like Bulgari Pour Femme, a lot actually, but I think I should try it again on a day when I'm alone just to be sure, so I can get to know it on my own.

Day 5: I put Bulgari Black on in the morning and let myself smell it for a while before my boyfriend did. This meant I had to go for a walk while he was waking up and getting ready, but that’s something I should probably do anyway—I like the city best in the early morning. I liked Bulgari Black, too, even better than Bulgari Pour Femme. It doesn't smell like flowers or fruit or even very much like perfume. It smells like cologne and like nighttime, so it felt incongruous with the sun and the summer weather but I liked it anyway.

Day 6: Last perfume. Six seemed like a lot when I ordered them but actually “the trials” don’t even last a week. Guerlain Mitsouko is an unfortunate one to end on, smelling like flowers in formaldehyde. Frankenstein flowers.

Day 7-14: Ever since I finished sampling all the perfumes I've just been using and reusing my little tester tube of Bulgari Black until finally there wasn’t any left. It smells good to me, and I've been getting more comfortable wearing it. I practice by putting it on around the house and now it feels good elsewhere too. It feels like a good secret, like when my boyfriend and I said we loved each other for the first time—I walked around town afterwards looking at strangers and thinking: “These schmoes have no idea this great thing just happened!”

I used to want to ride a motorbike. It looked so cool, but also scary, so I put off learning. Then a few years ago, while living in San Diego, my old boyfriend and I split up, he got the car and moved to Arizona with it, and I had no way to get to work and no money for a car of my own, so I bought a knock-off Vespa. Then I really had to learn. I took a class and practiced around my neighborhood. I ran into a dumpster once and got on the freeway once by accident, but nothing really bad happened, and by the time I left San Diego I was great at riding my fake Vespa and also really loved it. Partly because it had been scary to learn. It represented a triumph.

Once I read an interview with Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys. He wrote all the famous surf songs but he never actually learned to surf. In the interview he said he didn't want to learn now because he’s too scared of getting hurt or dying. He's old now.

Perfume is something I hadn’t been trying because I was (a) scared of failing and (b) embarrassed to put energy into learning something so, well, girly. Perfume isn’t physically dangerous, like tearing around on a motorbike or being in the barrel of a wave, but admitting that I wanted to learn about perfume and allowing myself the time to do so was an emotional risk. Being able to say “it’s research” gave me license to try things.

It’s also helped that this has all occurred during baseball season: the excesses of masculinity balancing those of femininity in the studio I share with my boyfriend—the crack of a bat and a whiff of Bulgari.

*

Back in Sephora, I smell a few things. Perfumes meant to evoke walking on the beach or strolling through a flower garden, eating candy or being French.

I spritz on test strips, which both the sales associate and I smell. “Hmm, no, not you, right?” he says, growing more familiar as we sniff together and make the appropriate faces: pursed mouth and wrinkled nose for not so good, raised eyebrows and downturned mouth for surprisingly not bad, gritted teeth and wide eyes for really, really bad. Having smelled as much as my nose can take, I ask the sales associate if they carry Bulgari Black.

“Oh of course,” he says, scanning the shelves until his eyes fall on a bottle the exact shape and color of a hockey puck with a silver lid. He picks it up reverentially and displays it like Vanna White.

“Would you like to smell it?”

“Yes, please.” Though I know what it smells like, it seems rude to tell him that after trying so many scents.

He sprays. It smells like night and cities and figuring things out.

“How much?” I ask, crossing my fingers. I should have checked the website first.

“One hundred, plus tax.” He says it apologetically. Though I’m wearing heels—another thing I’d taught myself while learning that it was okay to care, and to try, and to not get it right the first time—they are thrifted and scuffed, my bag overstuffed.

“Uh…” What is your womanhood worth? I wonder, and then, in the voice of my mom: If your womanhood has a price, then it’s not yours. And then, also: You’ve worked in retail. Ask the important question. “Do you work on commission?”

“No.”

“Oh good. I have to think about it. Thank you so much!”

Out of the store and onto the street. Heat. Halal. Tourists. Construction. Ambulances. I’d left the sanctuary.

Like the grown woman I am, I waited patiently. Sure enough, a week later I found Bulgari Black marked down on a perfume website: $35. I bought it, and use it sparingly, like holy water.