What's going on in beauty this week, from head to toe and everything in between.

Hairy history: Next time you're in Missouri, swing by Leila's Hair Museum, featuring centuries of ornaments and jewelry made from human hair, which is awesome and creepy in equal measures. There's also a Victorian Hairwork Society, if you want to get social about it. (via Makeup Museum)

...To Toe...

...To Toe...

Ms. Fix-Its: Taking the "blowout bar" service one step further, Fix Beauty Bar has mani-pedis that you can get while your hair is blown out—the sheer glamour of which did not go unnoticed by Deep Glamour, which features an interview with the cofounders this week.

...And Everything In Between:

...And Everything In Between:

Get your claws out: Vice president of Ask Cosmetics, a nail-care company, accused of defrauding the company of CND $700,000 over a four-year period.

Big gamble: Rajat Gupta, the Procter & Gamble board member convicted of insider trading, will remain free on bail while his appeal is pending, ruled a federal appeals panel.

Lose inches overnite!: The Ministry of Health in Dubai issued a public health warning about unscrupulous health and beauty social media advertisers (think weight-loss spam), including skin whitening products.

Rihanna and subversion: These two posts make nice companions to one another. First up, this blogger takes a good stab at answering what cuteness might look like when used as a tool of subversion: "Because women of color (excluding East Asian women) are scripted as inherently sexual, it may bring the subject/voyeur (read: society) into a troublesome gaze when they cannot view the objects (brown and black women of color) as sexual because they are non-sexualized when they perform cuteness." Then philosopher Robin James looks at one particular case of a woman of color toying with personae and subversion: Rihanna, and her use of lyrics and styles that mimic the violent dynamics she had in her relationship with Chris Brown: "As Angela Davis repeatedly demonstrates in her book on the blues, black female singers often use lyrics that superficially portray their victimization to critique the very racist misogyny that would victimize them. Why aren’t people at least granting the possibility that Rihanna is participating in this tradition?"

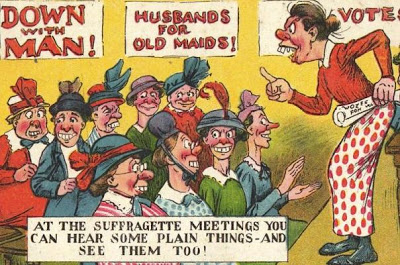

"Wherever Seth Rogen conceives with Katherine Heigl, the dream lives on": We're not quite done yet with the Richard Cohen/James Bond "sexual meritocracy" bit, are we? Good. Then allow me to point you toward Ta-Nehisi Coates's piece on "democracy and the inalienable right to hit that."

Holy moley: Excited for Salon's new rotating "Body Issues" column, which promises to bring "a series of personal essays about obsessions with our own bodies." First up: Sarah Hepola, always a treat to read, on how she felt about her dusting of moles. I'm mole-y myself so particularly appreciated this piece, though it's funny: Unlike Hepola, I was never self-conscious about my moles until an acquaintance playfully started counting the moles on my arms, and even after that it's just something I'm aware of, not ashamed of—I wear sleeveless shirts a lot, and short skirts. I was excruciatingly self-conscious about pretty much every other part of my body, but never my moles. Funny what our brains decide to zero in on, eh?

Game-changer: Deep Glamour takes a look at Gordon Parks, who effectively changed the course of fashion photography singlehandedly by taking models out of the studio and planting them on the streets.

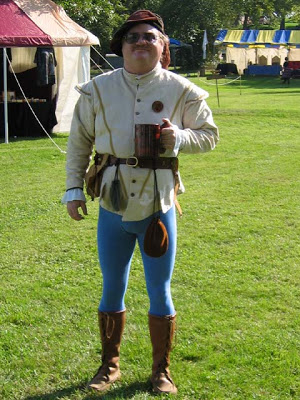

This dude is trying to sell you nail polish but it's okay because there are ladies in the background so he's not, like, gay or anything

Strong enough for a man: As someone who firmly rolls her eyes at nail polish lines for men—not because I think men shouldn't wear the stuff but because it's not like, oh, every single shade in their collections doesn't already exist—I was intrigued by this interview with the CEO of Alphanail. "Q: If girls' products are good enough for gay men, why not for straight men? A: They should be. Honestly, it’s a marketing strategy." Yessir, it is!

Meow!: Zara tells us about the pin-on mood-indicating kitten tail that's hitting—where else?—Japan, and I die.

Women, food, and the therapeutic narrative: Charlotte Shane argues that the social narrative around food is disordered, and we're not talking in a Michael Pollan way either: "To have moderation in all things except immoderation echoes the close-fistedness of my most manic restrictions." I'm still wrestling with this provocative, laser-sharp piece, which in part makes a case for the semi-normalization of behaviors that are conventionally seen as troublesome in women, because it soundly echoes my own (disordered) eating history—a history that has troubled me, and that isn't "over" even though I've publicly gone through my own therapeutic narrative (the concept of which I discuss here about body image, but which applies to disordered eating as well).

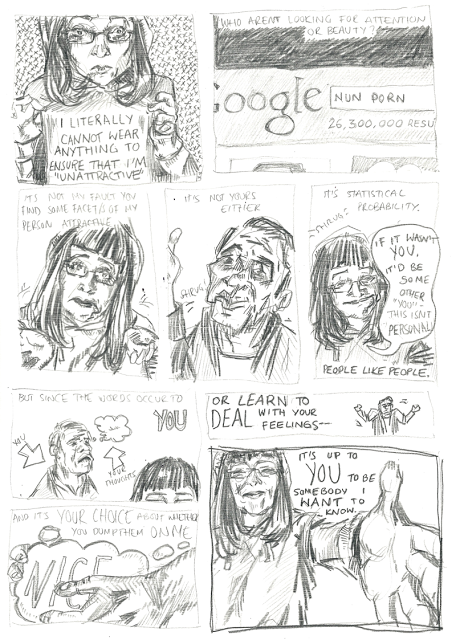

"Like": This Jessica Valenti piece on women and likeability has a roundabout connection to beauty—yes, women want to be pretty because that has a singular value, but there's also a component of conventional beauty that's about placating others. Still wrapping my mind around this one (I'm very much a honey-not-vinegar type, and I can't help but feel like I'm being a little scolded for that—but I also know my niceness has been a detriment at times).

Wish list: Makeup artist (and fantastic blogger, and if you enjoy my roundups you should absolutely be reading hers as well) Meli Pennington at Wild Beauty has an impeccably curated list of beauty books that serves as a nice tip list if you're holiday shopping.

On what we don't look like: These two entries complement one another: Kate, with her characteristic elliptical grace, on giving herself permission to occasionally feel disappointed about the way she looks: "But I have all of these other images of what beauty looks like stuck in my eyes, so that they waver, floating, translucent, over my face. All of these other faces taunt my own. And they’re the pretty ones. They are how I should have looked, might have looked, if I were luckier. And I think it’s fair to think that way...there is so much belief in beauty as something critical for girls and women." Sally arrives at a similar conclusion, through examining the ways we're encouraged to treat celebrities—with their personal trainers and stylists and makeup artists and a job in which looking flawless at all times is a requirement—as role models isn't helpful, but can be liberating: "I’ll never look like that. And acknowledging that fact is actually quite freeing."

Infidels: Phoebe Maltz Bovy muses on the role of male beauty in infidelity. "[Women involved in betrayal], I'd imagine...follow certain scripts, and conform to a narrative about wanting to be found beautiful themselves. Well, perhaps so, but why by whichever man in particular? Might it have something to do with his looks?"